SUBHEAD: Two reasons why this American climate alliance "We Are Still In" could save the world.

By Tegan Tallulah on 19 June 2017 for The Climate Lemon -

(

http://theclimatelemon.com/we-are-still-in-climate-coalition/)

Image above: Supporters of Paris Climate Accord gather to demonstrate on the Andy Warhol Bridge over the Allegheny River in down town Pittsburgh after Trump rejected world climate agreement. Pittsburgh continues its plan to power itself with 100% renewable energy by 2035. From original article.

Image above: Supporters of Paris Climate Accord gather to demonstrate on the Andy Warhol Bridge over the Allegheny River in down town Pittsburgh after Trump rejected world climate agreement. Pittsburgh continues its plan to power itself with 100% renewable energy by 2035. From original article.

There are many reasons why Donald Trump is dangerous. His egotism, his authoritarianism, his disregard for facts, his bigotry towards women, Muslims, Mexicans, disabled people… There’s quite a few contenders.

But arguably his most dangerous quality is his views on climate change. Because this is an area where he can damage the whole world, and that damage can reverberate for centuries.

Scary, huh? All through Trump’s campaign he promised to pull the USA out of the

Paris Climate Deal, and sure enough, after a period of intense um-ing and ah-ing, he confirmed he would do so. Queue an impressive display of horror and condemnation from leaders around the world.

I was all prepared to be severely depressed about this, but then something amazing happened.

American business leaders, city mayors, state governors and university principals, stood up and said ‘no, we’re not going to put up with this shit’. (I’m not sure that’s a direct quote, I’m paraphrasing).

This unprecedented alliance – known as the ‘We Are Still In coalition’ has formed around support for the Paris Agreement and recognition that climate action is their obligation to the world, and is good for America anyway.

This is incredibly powerful, for two main reasons: the science and the symbolism. By that I mean the physical direct impact on the carbon emissions of America and the world, and the psychological, cultural and political impact that such a move has on the rest of the world, and the indirect climate effect of that.

But before we dive into these two main points, let’s just recap on why the USA’s response to climate change is so crucial for the world, and what this new American climate alliance actually is.

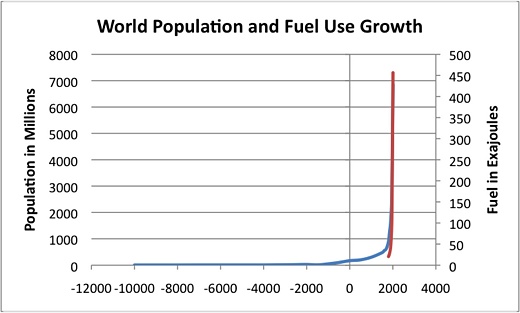

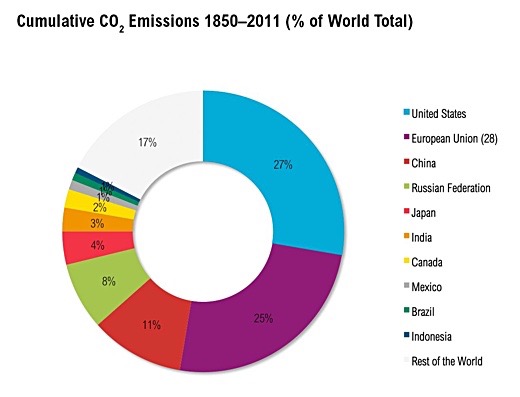

Quick note on why USA is so crucial to climate action

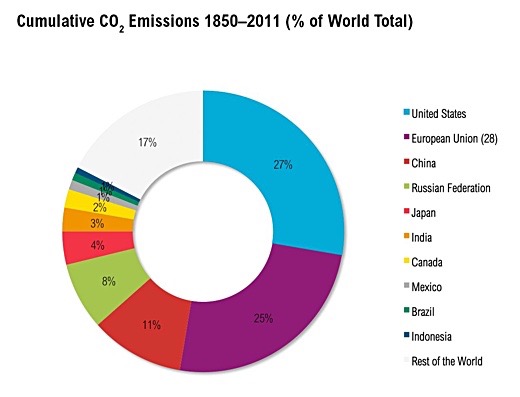

The USA has by far the biggest historical carbon emissions and one of the highest emissions per person in the world. This means they are one of the countries most responsible for causing this climate crisis. Quite frankly, it’s amoral to walk away from your responsibilities. If you make a mess, you should at least help clean it up.

Even if the USA wasn’t a heavy polluter, there would be

a strong argument that they should be a key player in sorting out the mess anyway, just because they have the power to do so.

They are the richest country in the world and are routinely regarded as the most powerful, due to immense wealth and military might and ‘cultural power’ – a more fuzzy concept that includes everything from having the most UN diplomats to Hollywood movies dominating the global media market.

Image above: Pie chart of percentage of cumulative CO2 emissions between 1850 and 2011 by country. From World Resource Institute (http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/11/6-graphs-explain-world%E2%80%99s-top-10-emitters). Click to enlarge.

Image above: Pie chart of percentage of cumulative CO2 emissions between 1850 and 2011 by country. From World Resource Institute (http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/11/6-graphs-explain-world%E2%80%99s-top-10-emitters). Click to enlarge.

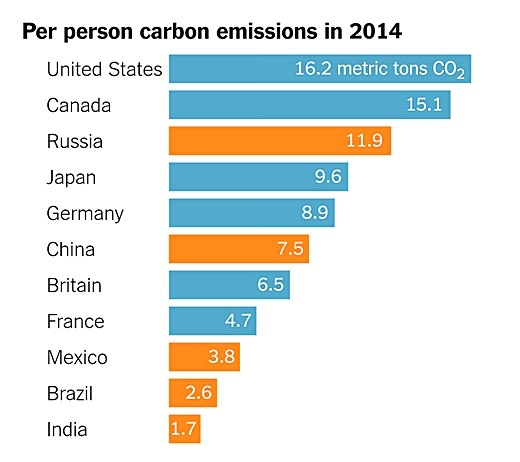

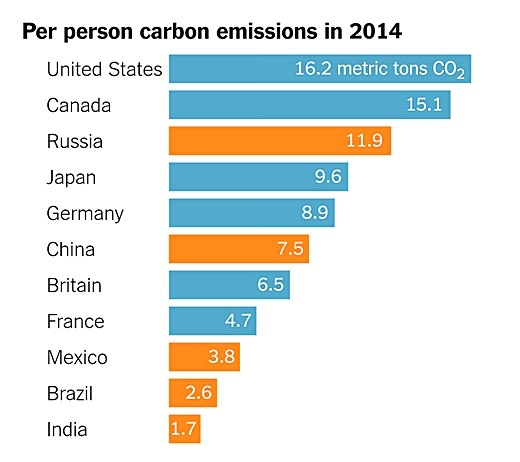

Image above: Bar chart of per person carbons emissions in metric tons of CO2 emissions in 2014 per person by country. From original article. This chart was adjusted from the 2011 data from the World Resource Institute (http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/11/6-graphs-explain-world%E2%80%99s-top-10-emitters). It separates countries in the European Union. Note, the United States past Canada in CO2 emissions per person. The world average is about what Britain's emissions are (less than a third of USA's. Click to enlarge.

Image above: Bar chart of per person carbons emissions in metric tons of CO2 emissions in 2014 per person by country. From original article. This chart was adjusted from the 2011 data from the World Resource Institute (http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/11/6-graphs-explain-world%E2%80%99s-top-10-emitters). It separates countries in the European Union. Note, the United States past Canada in CO2 emissions per person. The world average is about what Britain's emissions are (less than a third of USA's. Click to enlarge.

So what is the "We Are Still In" coalition?

The We Are Still In coalition is a loose voluntary group of city mayors, state governors, CEOs, investors and university principals who have signed a pledge, on behalf of their communities and organisations, and an open letter to the UN, stating that they are still committed to the Paris Agreement.

They have promised to use their respective powers to lead climate action in their communities and businesses, aiming to meet or exceed the USA’s commitments under the Paris Agreement. (Which by the way is a 26-28% cut in emissions compared to the 2005 level by 2025, and even under Obama they were likely to miss that target).

So who’s actually signed up? The pledge has 1219 signatories so far, and growing. This includes:

- 9 states: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia and Washington

- 125 cities. Including Washington DC, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Pittsburgh…

- 902 businesses and investors. Including Amazon, Apple, Google, Gap, Mars, Nike…

- 183 universities and colleges.

You can check out the

full list of signatories and their open letter here.

The cities and states represent 120 million Americans and a GDP of $6.2 trillion. The businesses together have combined revenue of $1.4 trillion.

This means 38% of the American population and at least 35% of their GDP is covered by this new alliance. If just the 9 states were a country, that country would be the fifth richest and sixth highest polluter in the world. So it’s a pretty big deal.

The philanthropist, business investor and former Mayor of New York Michael Bloomberg has been instrumental in coordinating this alliance, and he has even

pledged to donate $15million from Bloomberg Philanthropies to the UN, to replace funding from Washington they’ll now miss out on thanks to Trump.

Although he’s certainly been a leader, it has also been a collaborative effort between 21 nonprofit groups, including C40 Cities, CDP (who I am starting a new job with next month!), WWF and others, who really pushed this forward.

The coalition wants to participate in the Paris Agreement, but there is currently no formal way for them to do so on America’s behalf, as it is an agreement between sovereign nations. However the Accord does call for ‘non-state actors’ to be involved. How this would work in practice is still being worked out.

The two big reasons why this is so incredible

Okay. Now into the real tofu and potatoes of this post. "Science" and "Symbolism"

The science

As this Alliance covers 38% of the American people and at least 35% of their GDP, they have significant power to influence the carbon emissions of the country. Due to the USA’s federal structure, states and cities have fairly extensive powers. The large companies have huge power through their supply chains.

However, even under Obama, the USA was not on track to meet its climate targets. With Trump’s hostile regressive stance and deregulation of pollution, it’s going to be even tougher to meet them.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t.

I’m fairly optimistic about their chances, as it looks like the hostility of the federal government is actually acting as an effective motivator to people who would have just sat back and done little otherwise. There really is a huge groundswell of support for the Paris Agreement emerging from the bottom up, and it’s not clear how far that momentum will go.

It’s difficult to estimate what percentage of the USA’s carbon emissions are represented in this coalition, because many of the members are overlapping – so you can’t just add up all their emissions. But the nine states alone

represent 17% of USA emissions – and that’s without all the major cities and businesses outside of those states.

The symbolism

Direct cuts in carbon emissions are not even necessarily the most influential thing about the We Are Still In coalition. The symbolism is incredibly powerful. Here are cities, states and businesses directly defying Trump by saying: ‘You made the wrong decision. You do not speak for us. We are still in the Paris Agreement’.

The fact that Washington and New York were two key signatories will be a particular slap in the face for Trump. The small city of Pittsburgh is also notable because in his speech he declared ‘I was elected to represent Pittsburgh, not Paris’.

The mayor of Pittsburgh resented his city being used as an excuse like this, especially considering they already had a climate action plan to go 100% renewable powered. He publicly disagreed with the decision to leave the Paris Agreement, and joined the We Are Still In coalition instead.

The President also argued that climate action is bad for business and he would prioritise business. And what response did he get?

Tesla CEO Elon Musk and Disney CEO Bob Iger promptly quit his presidential advice council in protest. The ‘climate vs business’ position has become more discredited than ever, as over 900 businesses have joined the coalition.

Many of the most outspoken members are American-based tech giants, like Google, Apple and Amazon. They argue that in the short term, there are great business opportunities to be had from clean energy and greener products – and in the long term all business depends on a stable climate.

When Trump said he was going to exit the Paris Agreement, a real worry was that other countries would lose motivation and think ‘if the richest most powerful country, that has some of the highest emissions, is going to walk away, then there’s no point me doing anything.

Screw it, I’m out’. For some, that was an even bigger problem than the USA’s actual emissions. Because it posed the threat of unravelling the delicate international consensus that had been pieced together –finally, painfully- on this global issue.

Luckily, other national leaders were keen to reconfirm their support and to condemn Trump’s decision. (Even Kim Jong-un, who called the move “the height of egosim”, with zero self-awareness).

What this coalition does, is it assures the international community that America is still at the table. Even if the central government pulls out, America will still be informally committed to the Paris Agreement, through this broad and growing coalition.

Conclusion – Thank you America!

It’s imperative for the whole world’s future that America does not walk away from tackling climate change. Despite Trump’s damaging and regressive decision, it now looks like this will not be the case. Where the government steps down, leaders from local government, business and civil society will step up.

This has given me hope for the future. Thank you to everyone involved – thank you to the signatories, the organisers, and to all the everyday Americans who support it.

.