SUBHEAD: In 2020 we found ourselves in a world where we could not agree on what is reality.

By Richard Heinberg on 18 December 2020 for Resilience.org -

(https://www.resilience.org/stories/2020-12-18/2020-the-year-consensus-reality-fractured/)

Image above: Volunteers help clean up the parking

lot outside a Best Buy store, Monday, Aug. 10, 2020, after vandals

struck overnight in the Lincoln Park neighborhood in Chicago. From (https://www.hotsr.com/news/2020/aug/11/hundreds-ransack-downtown-chicago-businesses/).

Virtually everyone agrees that 2020 was an abomination. An entire industry of opinion writers is busying itself with end-of-year hand wringing, scouring every online thesaurus for adjectives to express just how horrible the last twelve months have been.

But what facet of the awfulness to focus on? For the appalled chronicler, the most obvious starting points are the coronavirus pandemic, which has left illness, death, shuttered businesses, and lost jobs trailing in its wake, and the chaotic US presidential election, in which the soundly defeated incumbent has attacked and seriously weakened the very foundations of democracy on his way out the door.

These two baskets of grim news (pandemic and election) have been accompanied by a shift in the national (and, to some extent, global) zeitgeist—a shift that’s been obvious to anyone paying attention, but that’s nevertheless challenging to capture in words.

Let’s call it the fracturing of consensus reality. While it won’t be the top story of the year according to most news roundups, it may end up being just as impactful as anything else that’s happened during our latest orbit of the sun. And that’s saying something.

What’s Real? Let’s All Agree

As social and linguistic creatures, we humans—operating in groups—create shared mental worlds. We perceive sensory data, then we verbalize and conceptualize those perceptions, and finally we check our verbalized and conceptualized accounts of reality with other people.

Over time, a consensus emerges.

This language-mediated reality-building process is hardly new; it’s been going on since we all lived by hunting and gathering. Then, everybody within their little groups shared the same stories and the same basic mental map of the world.

After we adopted agriculture, social classes and full-time division of labor ensued. With slavery, kings, and a dramatic reduction in the social power of women, consensus reality became more of a Venn diagram, with the king having the final word in defining the overlapping region on the diagram representing consensus.

Later, the emergence of writing and Big God religions enabled reality to be codified for empires, and elements of the dominant consensus (e.g., Roman law and Christianity) could be spread among alien cultures.

For most Europeans, even as dynasties came and went, reality remained essentially whatever the Bible, the church, and the king or emperor said it was.

Consensus reality was never consistent or complete and never a correct map of what it purported to represent; it was always an approximation skewed by power relations.

Some people’s realities were privileged, while other people’s were marginalized, excluded, or intentionally destroyed. And there were always blind spots—actual trends, vulnerabilities, and consequences that nobody noticed or talked about, such as the gradual depletion of natural resources—that only became “real” when they could no longer be ignored.

The modern era (from roughly 1500 on) brought new sources of diversity to the consensus-building process.

As Europeans conquered societies around the globe, “reality” began to reflect the sounds and flavors of these diverse cultures; the result was everything from jazz to fusion cuisine. Meanwhile, the power of commerce greatly increased, reducing the influence of church and aristocracy.

Increased diversity and a shift toward commercial primacy were accompanied by new integrative trends in the process of collective reality-building. Principal among these was the emergence of science—a self-correcting method for discovering objective truth.

Of course, science had its blind spots, too (for example, it was often subject to commercial influence—witness the long lags in recognizing the nasty side effects of tobacco and pesticides), but it was persuasive: assertions could be tested by controlled experiment.

Over the decades, science built formidable structures of knowledge that most people lacked the expertise or temerity to question, but that could be verified by anyone with the necessary resources. Reality became “enlightened.”

Another integrative trend consisted of the development of new communication tools—the printing press, and later radio, movies, and television.

Increasingly, through these media, nearly everyone was exposed to common facts, ideas, and images. The wealthy banker and the destitute farmer uprooted by the dust bowl were marinated in the same Hollywood imagery, and the same civics homilies taught in compulsory public schools.

Cracks in the Modern Consensus

The emerging global consensus suffered a couple of serious ruptures during the modern era. In Europe, fascism brought more than a new set of political power relations; it created a mental universe so dominated by notions of racial and national superiority that it demanded the rewriting of textbooks.

And in Russia, communism built a narrative in which the dictatorship of the proletariat—under constant attack by the forces of capitalism—must ultimately prevail, leading to a workers’ paradise.

Both fascists and communists used new mass communication tools (radio, movies, and newspapers) to give their consensus realities force and credibility.

Even science could be repurposed to support alternate realities. In the Soviet Union, the state decided to back an alternative to natural selection and science-based agriculture.

The originator of this heterodox set of views, Trofim Lysenko, became Director of the Soviet Union’s Academy of Agricultural Sciences, where—with Stalin’s approving help—he rooted out the study of Mendelian genetics and taught instead the theory that characteristics acquired by parents can be directly transmitted to their offspring.

Opponents of Lysenko were accused of “mysticism, obscurantism, and backwardness,” then banished to Siberian work camps. As a result, biological science in the Soviet bloc was set back decades.

After the defeat of fascism in WWII and the fall of the Soviet bloc, the West’s consensus—shaped largely by the US—seemed to become reunified and stabilized.

Political scientist Francis Fukuyama called it “the end of history.”

But blind spots persisted and grew. Some of these profoundly shaped not just the dominant worldview itself, but the contours of daily life for multitudes.

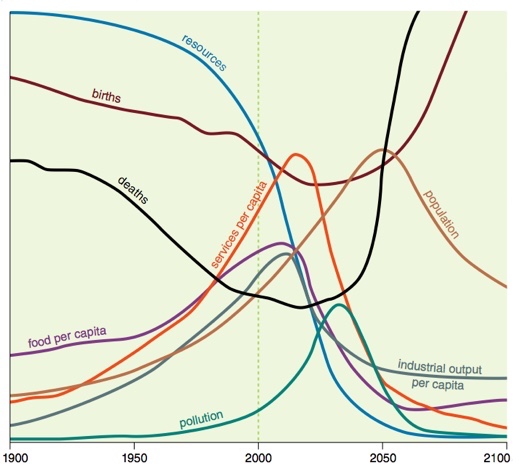

One telling example: the so-called science of economics codified for nearly everyone the false assumption that perpetual growth in industrial activity is possible, and denied all evidence to the contrary.

Economics concealed other blind spots as well, as it continually ignored widespread signs that the “free market” does not in fact benefit everyone, and that people do not actually behave like idealized rational self-interest-maximizing robots.

Some persistent and periodically worsening cracks in the consensus ripped along economic, ethnic, or political fault lines: especially during the Jim Crow era, African-Americans and European-Americans in southern US states inhabited sharply different realities, and stark inequities have persisted to the present.

Other cracks, fed by suspicions that powerful people were manipulating the consensus to their own benefit, led to what came to be known as conspiracy theories—including doubts about the official accounts of the JFK assassination and 9/11, as well as misgivings about the safety and “real” purpose of water fluoridation and vaccination.

Meanwhile, communications media were evolving still further.

While radio and television had a largely unifying effect during the 20th century, the internet and social media are proving to be disintegrative to consensus in the 21st. Algorithms capture users’ interests and prejudices and feed them news and opinion articles that lead them to have ever-more-extreme views.

“Do you think the government is suppressing information about space aliens? You don’t know the half of it! Read this!”

The radicalizing propensity of social media was a factor in the sudden political ascendancy of Donald Trump, who acted as both symptom and driver of consensus breakdown. As a real estate developer and reality TV personality, he seemed an exceedingly inexperienced and unlikely candidate for the top political office in the country, and arguably the world. His intellect and ethics were widely suspect.

But he had the ability to give utterance to the grievances of a sector of the populace that feels left behind—people of mostly European ancestry in low-density towns and rural areas across the nation (in recent decades, most of America’s wealth and cultural attention has flowed to high-density, multi-ethnic cities).

Even if Trump could not change the material circumstances of small-town families, he could make them feel as though they had a voice. Ironically—and perhaps therefore somehow even more fittingly—it was the voice of a gaudily privileged New Yorker.

But it was an angry voice, and it spoke in words of few syllables. He was the first Twitter President. The Trump team’s communication strategy, in the immortal words of former top adviser Steve Bannon, was to “flood the zone with shit.” Disruption of consensus reality wasn’t a regrettable side effect of their efforts; it was a central goal.

2020: The Dam Breaks

In short, prior to the year now ending, consensus reality in the US was already starting to crumble. But 2020 delivered two sledgehammer blows: a pandemic and a polarizing presidential election.

First, the pandemic.

As many observers have pointed out, COVID-19 has greatly varying infection and death rates by nation, and countries with higher levels of social cohesion have generally tended to do better at combatting the disease.

The United States has fared the worst of all countries in raw numbers, with over 17 million total cases so far and over 300,000 deaths (about a dozen smaller countries, including Belgium and San Marino, have suffered higher per capita rates of infection and mortality). Currently the US is seeing over 200,000 new cases each day and roughly 2,500 deaths.

Unless the trend changes, total mortality for the country may eventually begin to rival that of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, in which about 675,000 died (though the per capita death rate will almost certainly not be as grim, given today’s far larger population).

Why has the US suffered such a horrific outcome?

Much of the blame certainly must be borne by President Trump and his political appointees and allies in the federal government. They mounted almost no coordinated national pandemic response; instead, states were left to formulate their own policies and to compete with each other for medical supplies.

Messaging from the executive branch was likewise unhelpful or downright counterproductive: in the early weeks, when the virus was largely just a distant menace and preparations could have made a huge difference, the President dismissed the need for concern (on January 22, he told a CNBC interviewer, “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”).

Then, when it became clear that sickness was spreading and people were dying, Trump invented the term “China virus,” evidently seeking to deflect blame while still failing to forge a national response plan. Later in the year, as economic and political concerns took the spotlight,

Trump returned to almost completely ignoring the disease, even omitting attendance, for weeks at a time, at meetings of his coronavirus task force.

With no clear messaging from the President, it was essential that the appropriate federal agencies step in. But here again the response faltered.

The Centers for Disease Control at first advised the public against mask wearing, despite clear evidence that masks were effective at stopping the spread of the disease. Only later, once masks became more widely available, did the CDC change its recommendation.

But this self-contradiction had undercut the agency’s credibility. Many people continued to believe that mask wearing is ineffective, while the President encouraged his followers to see mask mandates as government overreach.

Conspiracy theories immediately filled the vacuum of leadership and consistent government messaging.

Millions of people, stuck at home under lockdowns, were spending more time than ever on social media and Google, exploring ideas and opinions about the coronavirus. A pair of YouTube documentaries titled “Plandemic” became instant sensations.

Many people adopted the view that there simply is no pandemic, and that the “fake news” media ginned up the story as a way to enable globalist liberal elites to exert more control over citizens and the economy.

Now that vaccines are on the horizon, the conspiracy mill is cranking harder and faster than ever. While the anti-vax movement has been slowly simmering for decades, its current leaders’ books are suddenly among the top-sellers on Amazon.

Up to a third of Americans say they will likely refuse to take a vaccine when it is available. While many people hope that the advent of vaccines will halt the pandemic in its tracks, anti-vax fervor, along with the soaring rate of infections, may mean that the disease will continue to spread and kill far into the new year.

If Americans were divided prior to the pandemic, their tribalism only intensified as the decision about whether to wear a mask became an instantly visible expression of group identity.

But division was deepened also by the fact that 2020 was a presidential election year.

Elections are always polarizing. That’s the point: each voter must choose one candidate or another; “all of the above” is not an option.

But this election season pushed the polarization needle far into the danger zone. Democrats steeped themselves in books and articles detailing accusations that Donald Trump presents all the clinical symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder, and that he is an authoritarian, a rapist, a tax cheat, a business fraudster, a Russian puppet, and a traitor.

At the same time, followers of QAnon (who is supposedly a patriotic government insider) spread the notion that leading Democrats are Satan-worshiping pedophiles running a global child sex-trafficking ring, while Trump—a messiah sent by God—heads a heroic behind-the-scenes effort to preserve decency, freedom, and Christianity (QAnon believers now occupy seats in Congress and many state houses).

The election outcome was unequivocal.

Biden bested Trump by 7 million popular votes, with electoral votes stacked 306 to 232. Even Republican election officials in swing states said the balloting went off with scarcely a hitch. But Trump, evidently unwilling to be seen as a loser (or perhaps wishing to avoid prosecution for financial crimes once he leaves office), claimed that the election was rigged and that he had actually won.

A flurry of almost 60 lawsuits followed, two making their way to the Supreme Court; all were dismissed. No convincing evidence of widespread irregularities was produced. Nevertheless, Trump’s followers adopted the narrative that millions of dead people had voted for Biden, and that suitcases full of illicit Biden ballots had been surreptitiously delivered to vote tabulators. According to one poll, only a quarter of Republicans think Biden was legitimately elected.

A steady drumbeat of evidence-free assertions resounding through right-wing media channels and parroted by Republican elected officials (who fear retribution from Trump’s base) has created a formidable alternate reality in which Trump won fair and square, while Biden is being falsely elevated to the highest office.

Consensus Dynamics

Cognitive dissonance—the holding of contradictory thoughts or beliefs—makes people miserable. And when a person’s own interpretation of reality runs counter to the consensus reality, some degree of paranoia or depression often results.

Alternatively, a person unmoored from the dominant consensus may become a dedicated paradigm warrior intent on converting others to their own views, sometimes even by violence.

The loss of consensus is therefore also problematic for society as a whole.

People who have left the consensus behind may disregard or flout norms (such as longstanding informal rules with regard to elections and Congressional procedures). Society then becomes less capable of solving problems; and so, if economic, social, or environmental crises materialize, societal collapse of one sort or another becomes a real possibility.

As individuals find themselves not just disagreeing on politics or religion, but living in different and directly conflicting mental universes, they individually experience cognitive pain and anguish. Families are torn apart, friendships severed.

But the collective risks of consensus breakdown go deeper, and include the possibility of widespread rage, pushing society toward civil violence, coup, or state failure. If, as is often the case, the fracturing of consensus results in (or is caused by) strong feelings of grievance among one group against another, a cycle of retribution may ensue.

Recent brain research by James Kimmel, Jr. at the Yale University School of Medicine shows that the brain on grievance craves retribution in much the same way a brain addicted to heroin craves more heroin.

Is the fracturing of consensus reality a symptom of societal decline due to other factors (such as economic crisis or limits to vital resources), or is it an independent variable, capable of causing collapse by itself?

In my view, the former is more likely the case: if a society is doing well economically, it is usually able to resolve occasional cognitive contradictions over time. A polarizing demagogue (like Joseph McCarthy or George Wallace) may appear, but the status quo eventually reasserts itself.

However, if a society is experiencing an economic, political, or social emergency, consensus breakdown may contribute to a self-reinforcing process of collapse.

People’s views of reality don’t diverge arbitrarily and without cause. They do so because people’s self-interests (which may differ by income, status, region, religion, or ethnicity) are becoming further divided. The divergence of worldviews is thus a secondary problem.

But once consensus begins to shatter, people’s interests are likely to diverge even further as bifurcating worldviews create economic and social islands. People may even separate geographically, moving to be closer to people with whom they share values and views.

Further, if an increasing majority people in a given community are espousing a new shared belief, others may feel compelled to alter their previous beliefs in order to belong.

The fragmentation of consensus reality isn’t just a war of ideas. It is a more profound and disturbing process both psychologically and socially. People who have abandoned, or who have been abandoned by, the consensus may find dubious new beliefs to cling to; but they may also become keenly aware of cultural blind spots that others continue to ignore.

They feel themselves flung into a new universe; the experience can be either terrifying or thrilling, or both.

One of the effects of loss of consensus is the lowering of social trust. Trust is the basis of cooperation, and high levels of cooperation are required for modern complex societies to function.

According to surveys by Pew Research Center, 71 percent of Americans think interpersonal trust has weakened in the past 20 years. There is a strong correlation between low trust and Trump voters—which could be an explanation for why the pre-election 2020 polls were inaccurate: people who are distrustful not only disproportionately voted for Trump but also refused to participate in polling surveys.

Because the costs to society of loss of consensus are obvious and considerable, societies invest heavily in maintaining a shared worldview.

But if there are severe and growing flaws in that consensus, keeping it whole may not be an option.

When consensus fractures into two directly competing narratives, some people may seek to resolve cognitive dissonance by claiming that the two narratives are equally valid. But this is a difficult stance to maintain, as the narratives are usually mutually exclusive. Take the current case with regard to the US presidential election: the main competing reality claims are not on equal footing with regard to facts or outcomes.

The “Trump really won” claim is simply fantasy; the “Biden really won” claim is backed by clear evidence that will result in the actual inauguration of a new President. But, in a way, facts are beside the point. Over a third of Americans are so alienated from the consensus that they prefer to believe obviously fabricated lies rather than to acknowledge demonstrable proof.

The new Republican “reality” is tenable not because it is based on anything physically verifiable, but because it is emotionally satisfying for people who refuse to accept the dominant narrative. In the post-Trump era, traditional Republican ideology (low taxes, states’ rights, limited government spending) becomes entirely expendable.

Any argument that “owns the Dems” is good, regardless how specious.

Democracy itself becomes an impediment to the goal of wrecking the consensus.

Defenders of the dominant worldview can’t understand why anyone would be so upset with it. Isn’t it based on science and established values and traditions?

Doesn’t the alternative represent a devolution into pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and deepening dissension?

To a certain extent, the fervor of the disestablishmentarian faction is traceable to economic and social trends mentioned earlier (the flow of wealth and power to coastal urban centers and the slow demographic shift of the country toward multi-ethnicity). The upholders of the mainstream consensus accept those trends, which their elites use to their own advantage, but they fail to take account of those left behind, or to see the holes and blind spots in the consensus they defend.

Perhaps the deepest blind spot in the current US consensus is that it has no satisfying and unifying vision, no coherent ideology; its main guiding value is simply “more.” Its implicit message: we must keep on doing what we’re doing (producing more wealth by turning more of nature into waste) because to do otherwise would result in economic Armageddon.

The best we can do is to somehow avert catastrophic climate change and reduce extreme wealth inequality with technical work-arounds, even as we continue to do the very things that cause those problems.

The central lie of the consensus is that the rising tide of economic growth will lift all boats . . . eventually. But eventually never seems to come. As the folly of expecting endless economic growth on a finite planet starts to reveal itself—via the need for ever more drastic measures to maintain the appearance of growth and to prevent widespread destitution—something has to give. People who feel unfairly treated as the impossible perpetual-growth machine decelerates begin fleeing the consensus, even if doing so leads them to curse imaginary scapegoats and believe obvious fictions.

Can the Old Consensus Be Repaired? Can a New One Be Built?

Joe Biden is central casting’s answer to the call for a tried-and-true figurehead to restore the old consensus. Anyone who’s not swept up in anti-elite fervor probably finds it easy to sympathize with his exhortation to bring America back together, and his intention to be President of all the people, including those who voted against him.

However, Biden faces daunting if not insurmountable challenges. These arise not just from fervent, defeated, and angry Trumpists, who may attempt to run a “shadow” presidency, countering every action of the new administration.

There are also hurdles inherent in the taming of the pandemic and the stabilization of the economy. Less widely acknowledged but perhaps most formidable of all is the challenge of finally coming to terms with the blind spots and lies embedded in the worldview that still runs the machinery of our economy and government. Consumerism—a way of organizing the economy that is fundamentally at odds with nature’s limits—is so deeply and implicitly woven into the warp and weft of modern America that only a cathartic collapse and renewal is likely to expunge it.

The best Biden can likely do, even if he has the strategic brilliance to propose a Rural New Deal, is to be a competent placeholder.

The perplexing fact is that we don’t know what kind of new consensus may emerge, or when.

Indeed, it is entirely possible that, in the context of energy and economic decline, the human ideasphere will remain fragmented from now onward.

However, I’d like to think that a new consensus is indeed possible, and that it will comprise the best of what we humans have learned so far.

And, though what follows is entirely speculative, it seems appropriate to close this essay with an exploration of what that consensus might look like.

Science would be an obvious candidate for inclusion, blind spots and all: its self-correcting mechanism tends to deliver improving approximations of truth with regard to physical reality.

Of course, in a world with a smaller and slower economy and much less energy available, only comparatively small and simple experiments might be possible, but it’s the method that matters.

Science can’t tell us much about values and goals. For those, knowledge is less important than wisdom. And wisdom comes from intelligent self-control. As sages have always taught, it is in the taming of selfish urges that we find compassion and contentment.

After the environmental and social mayhem that our two-century fossil-fueled consumerist mania will ultimately and undoubtedly unleash, I think we are likely to develop a strong and healthy collective skepticism regarding the aggregation of power for its own sake.

A sustainability-oriented worldview would acknowledge the ongoing need for a low and stable population relative to environmental carrying capacity. And it would prize sufficiency, equity, resilience, and happiness above accumulation and ostentatious display.

Our remarkable human capacities for language and tool making have gotten us into plenty of trouble over the millennia, never more so than now. A healthy consensus worldview would channel those outsized abilities away from geopolitical dominance and the production of wealth for the few, and toward the democratic (rather than just elite) production of beauty in all its possible forms—including poetry, literature, movement, music, art, drama, and architecture. And it would guide aesthetic appreciation toward the enhancement and emulation of nature.

Finally, a future consensus would take account of varying human needs, proclivities, modes of expression, histories, brain chemistry, and more, seeking reconciliation and community rather than exploitation and dominance.

Such a consensus reality, such a culture, is far from where we are now. Between here and there sits a valley we must cross. If we travel together, we have a better chance of arriving safely on the other side. That requires healing the divisions among us, if and when we disagree.

Have a peaceful holiday season.

.