SUBHEAD: However big we’re thinking about the effects of this pandemic, we can think bigger.

By Jeremy Lent on 3 April 2020 for Resilience -

(

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2020-04-03/coronavirus-spells-the-end-of-the-neoliberal-era-whats-next/)

Image above: Detail of painting of the sack of Rome in 410 titled "Barbarians at the Gate" by Thomas Cole in his series of five paintings of Roman history entitled "The Course of Empire". From (https://medium.com/@robertos/the-fall-of-the-roman-empire-81eae500bdc0).

Think Bigger

Image above: Detail of painting of the sack of Rome in 410 titled "Barbarians at the Gate" by Thomas Cole in his series of five paintings of Roman history entitled "The Course of Empire". From (https://medium.com/@robertos/the-fall-of-the-roman-empire-81eae500bdc0).

Think Bigger

Whatever you might be thinking about the long-term impacts of the coronavirus epidemic, you’re probably not thinking big enough.

Our lives have already been reshaped so dramatically in the past few weeks that it’s difficult to see beyond the next news cycle. We’re bracing for the recession we all know is here, wondering how long the lockdown will last, and praying that our loved ones will all make it through alive.

But, in the same way that Covid-19 is spreading at an exponential rate, we also need to think exponentially about its long-term impact on our culture and society. A year or two from now, the virus itself will likely have become a manageable part of our lives—effective treatments will have emerged; a vaccine will be available.

But the impact of coronavirus on our global civilization will only just be unfolding. The massive disruptions we’re already seeing in our lives are just the first heralds of a historic transformation in political and societal norms.

If Covid-19 were spreading across a stable and resilient world, its impact could be abrupt but contained. Leaders would consult together; economies disrupted temporarily; people would make do for a while with changed circumstances—and then, after the shock, look forward to getting back to normal.

That’s not, however, the world in which we live. Instead, this coronavirus is revealing the structural faults of a system that have been papered over for decades as they’ve been steadily worsening.

Gaping economic inequalities, rampant ecological destruction, and pervasive political corruption are all

results of unbalanced systems relying on each other to remain precariously poised. Now, as one system destabilizes, expect others to tumble down in tandem in a cascade known by researchers as “

synchronous failure.”

The first signs of this structural destabilization are just beginning to show. Our globalized economy relies on

just-in-time inventory for hyper-efficient production.

As supply chains are disrupted through factory closures and border closings, shortages in household items, medications, and food will begin surfacing, leading to rounds of panic buying that will only exacerbate the situation.

The world economy is entering a downturn so steep it

could exceed the severity of the Great Depression.

The international political system—already on the ropes with Trump’s “America First” xenophobia and the Brexit fiasco—is likely to

unravel further, as the global influence of the United States tanks while Chinese power strengthens.

Meanwhile, the Global South, where Covid-19 is just beginning to make itself felt, may face disruption on

a scale far greater than the more affluent Global North.

The Overton Window

During normal times, out of all the possible ways to organize society, there is only a limited range of ideas considered acceptable for mainstream political discussion—known as the

Overton window. Covid-19 has blown the Overton window wide open.

In just a few weeks, we’ve seen political and economic ideas seriously discussed that had previously been dismissed as fanciful or utterly unacceptable: universal basic income, government intervention to house the homeless, and state surveillance on individual activity, to name just a few. But remember—this is just the beginning of a process that will expand exponentially in the ensuing months.

A crisis such as the coronavirus pandemic has a way of massively amplifying and accelerating changes that were already underway: shifts that might have taken decades can occur in weeks.

Like a crucible, it has the potential to melt down the structures that currently exist, and reshape them, perhaps unrecognizably. What might the new shape of society look like? What will be center stage in the Overton window by the time it begins narrowing again?

The Example of World War II

We’re entering uncharted territory, but to get a feeling for the scale of transformation

we need to consider, it helps to look back to the last time the world underwent an equivalent spasm of change: the Second World War.

The pre-war world was dominated by European colonial powers struggling to maintain their empires. Liberal democracy was on the wane, while fascism and communism were ascendant, battling each other for supremacy.

The demise of the League of Nations seemed to have proven the impossibility of multinational global cooperation. Prior to Pearl Harbor, the United States maintained an isolationist policy, and in the early years of the war, many people believed it was just a matter of time before Hitler and the Axis powers invaded Britain and took complete control of Europe.

Within a few years, the world

was barely recognizable. As the British Empire crumbled, geopolitics was dominated by the Cold War which divided the world into two political blocs under the constant threat of nuclear Armageddon.

A social democratic Europe formed an economic union that no-one could previously have imagined possible. Meanwhile, the US and its allies established a system of globalized trade, with institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank setting terms for how the “developing world” could participate.

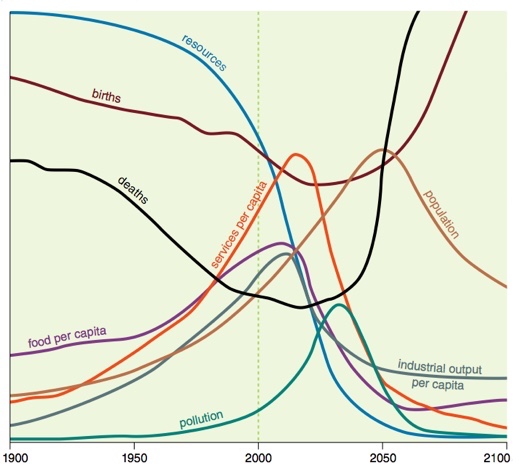

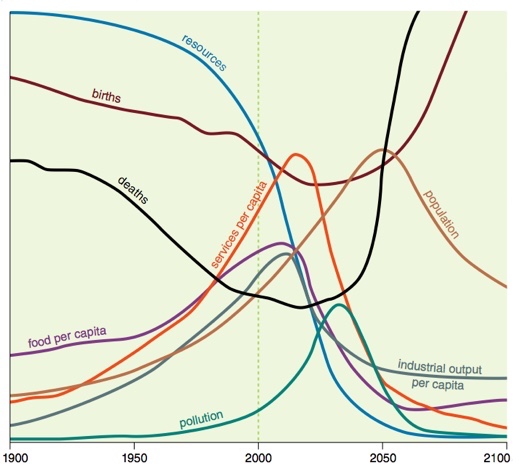

The stage was set for the “Great Acceleration”: far and away the

greatest and most rapid increase of human activity in history across a vast number of dimensions, including global population, trade, travel, production, and consumption.

If the changes we’re about to undergo are on a similar scale to these, how might a future historian summarize the “pre-coronavirus” world that is about to disappear?

The Neoliberal Era

There’s a good chance they will call this the Neoliberal Era. Until the 1970s, the post-war world was characterized in the West by an uneasy balance between government and private enterprise. However, following the “oil shock” and stagflation of that period—which at the time represented the world’s biggest post-war disruption—a new ideology of

free-market neoliberalism took center stage in the Overton window (the phrase itself was named by a neoliberal proponent).

The value system of neoliberalism, which has since become entrenched in global mainstream discourse, holds that humans are individualistic, selfish, calculating materialists, and because of this, unrestrained free-market capitalism provides the best framework for every kind of human endeavor. Through their control of government, finance, business, and media, neoliberal adherents have succeeded in transforming the world into a globalized market-based system, loosening regulatory controls, weakening social safety nets, reducing taxes, and virtually demolishing the power of organized labor.

The triumph of neoliberalism has led to the greatest inequality in history, where (based on the most recent statistics) the world’s twenty-six richest people

own as much wealth as half the entire world’s population. It has allowed the largest transnational corporations to establish a stranglehold over other forms of organization, with the result that, of the world’s hundred largest economies,

sixty-nine are corporations.

The relentless pursuit of profit and economic growth above all else has propelled human civilization onto a terrifying trajectory. The uncontrolled climate crisis is the most obvious danger:

The world’s current policies

have us on track for more than 3° increase by the end of this century, and climate scientists publish dire warnings that amplifying feedbacks could

make things far worse than even these projections, and thus

place at risk the very continuation of our civilization.

But even if the climate crisis were somehow brought under control, a continuation of untrammeled economic growth in future decades will bring us face-to-face with a slew of further existential threats. Currently, our civilization is running at

40% above its sustainable capacity. We’re rapidly depleting the earth’s

forests,

animals,

insects,

fish,

freshwater, even the

topsoil we require to grow our crops. We’ve already transgressed three of the

nine planetary boundaries that define humanity’s safe operating space, and yet global GDP is expected to

more than double by mid-century, with potentially irreversible and devastating consequences.

In 2017 over fifteen thousand scientists from 184 countries

issued an ominous warning to humanity that time is running out: “Soon it will be too late,” they wrote, “to shift course away from our failing trajectory.”

They are echoed by the government-approved

declaration of the UN-sponsored IPCC, that we need “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” to avoid disaster.

In the clamor for economic growth, however, these warnings have so far gone unheeded. Will the impact of coronavirus change anything?

Fortress Earth

There’s a serious risk that, rather than shifting course from our failing trajectory, the post-Covid-19 world will be one where the same forces currently driving our race to the precipice further entrench their power and floor the accelerator directly toward global catastrophe.

China has

relaxed its environmental laws to boost production as it tries to recover from its initial coronavirus outbreak, and the US (anachronistically named) Environmental Protection Agency took immediate advantage of the crisis to

suspend enforcement of its laws, allowing companies to pollute as much as they want as long as they can show some relation to the pandemic.

On a greater scale, power-hungry leaders around the world are taking immediate advantage of the crisis to clamp down on individual liberties and move their countries swiftly toward authoritarianism.

Hungary’s strongman leader, Viktor Orban, officially

killed off democracy in his country on Monday, passing a bill that allows him to rule by decree, with five-year prison sentences for those he determines are spreading “false” information.

Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu

shut down his country’s courts in time to avoid his own trial for corruption. In the United States, the Department of Justice has already

filed a request to allow the suspension of courtroom proceedings in emergencies, and there are many who fear that Trump will take advantage of the turmoil to install

martial law and

try to compromise November’s election.

Even in those countries that avoid an authoritarian takeover, the increase in high-tech surveillance taking place around the world is rapidly undermining previously sacrosanct privacy rights. Israel has

passed an emergency decree to follow the lead of China, Taiwan, and South Korea in using smartphone location readings to trace contacts of individuals who tested positive for coronavirus.

European mobile operators are

sharing user data (so far anonymized) with government agencies. As Yuval Harari

has pointed out, in the post-Covid world, these short-term emergency measures may “become a fixture of life.”

If these, and other emerging trends, continue unchecked, we could head rapidly to a grim scenario of what might be called “Fortress Earth,” with entrenched power blocs eliminating many of the freedoms and rights that have formed the bedrock of the post-war world.

We could be seeing

all-powerful states overseeing economies dominated even more thoroughly by the few corporate giants (think Amazon, Facebook) that can monetize the crisis for further shareholder gain.

The chasm between the haves and have-nots may become

even more egregious, especially if treatments for the virus become available but are priced out of reach for some people.

Countries in the Global South, already facing the prospect of disaster from climate breakdown,

may face collapse if coronavirus rampages through their populations while a global depression starves them of funds to maintain even minimal infrastructures.

Borders may become militarized zones, shutting off the free flow of passage. Mistrust and fear, which has already shown its ugly face in

panicked evictions of doctors in India and

record gun-buying in the US, could become endemic.

Society Transformed

But it doesn’t have to turn out that way. Back in the early days of World War II, things looked even darker, but underlying dynamics emerged that fundamentally altered the trajectory of history. Frequently, it was the very bleakness of the disasters that catalyzed positive forces to emerge in reaction and predominate.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—the day “

which will live in infamy”—was the moment when the power balance of World War II shifted.

The collective anguish in response to the global war’s devastation led to the founding of the United Nations. The grotesque atrocity of Hitler’s holocaust led to the international recognition of the crime of genocide, and the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Could it be that the crucible of coronavirus will lead to a meltdown of neoliberal norms that ultimately reshapes the dominant structures of our global civilization? Could a mass collective reaction to the excesses of authoritarian overreach lead to a renaissance of humanitarian values? We’re already seeing signs of this.

While the Overton window is allowing surveillance and authoritarian practices to enter from one side, it’s also opening up to new political realities and possibilities on the other side. Let’s take a look at some of these.

A fairer society. The specter of massive layoffs and unemployment has already led to levels of state intervention to protect citizens and businesses that were previously unthinkable. Denmark

plans to pay 75% of the salaries of employees in private companies hit by the effects of the epidemic, to keep them and their businesses solvent.

The UK has announced

a similar plan to cover 80% of salaries. California is

leasing hotels to shelter homeless people who would otherwise remain on the streets, and has authorized local governments to halt evictions for renters and homeowners. New York state is

releasing low-risk prisoners from its jails. Spain

is nationalizing its private hospitals.

The Green New Deal, which was already endorsed by the leading Democratic presidential candidates, is now being discussed

as the mainstay of a program of economic recovery. The idea of universal basic income for every American, boldly raised by long-shot Democratic candidate Andrew Yang, has now

become a talking point even for Republican politicians.

Ecological stabilization. Coronavirus has already been more effective in slowing down climate breakdown and ecological collapse than all the world’s policy initiatives combined. In February, Chinese CO2 emissions

were down by over 25%.

One scientist calculated that

twenty times as many Chinese lives have been saved by reduced air pollution than lost directly to coronavirus. Over the next year, we’re likely to see a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions greater than even the most optimistic modelers’ forecasts, as a result of the decline in economic activity.

As French philosopher Bruno Latour

tweeted: “Next time, when ecologists are ridiculed because ‘the economy cannot be slowed down’, they should remember that it can grind to a halt in a matter of weeks worldwide when it is urgent enough.”

Of course, nobody would propose that economic activity should be disrupted in this catastrophic way in response to the climate crisis.

However, the emergency response initiated so rapidly by governments across the world has shown what is truly possible when people face what they recognize as a crisis. As a result of climate activism, 1,500 municipalities worldwide, representing over 10% of the global population, have

officially declared a climate emergency.

The Covid-19 response can now be held out as an icon of what is really possible when people’s lives are at stake. In the case of the climate, the stakes are even greater—the future survival of our civilization. We now know the world can respond as needed, once political will is engaged and

societies enter emergency mode

The rise of “glocalization.” One of the defining characteristics of the Neoliberal Era has been a corrosive globalization based on free market norms. Transnational corporations have dictated terms to countries in choosing where to locate their operations, leading nations to

compete against each other to reduce worker protections in a “race to the bottom.”

The use of cheap fossil fuels has caused wasteful misuse of resources as products are flown around the world to meet consumer demand stoked by manipulative advertising.

This globalization of markets has been a major cause of the Neoliberal Era’s massive increase in consumption that threatens civilization’s future. Meanwhile, masses of people disaffected by rising inequity have been persuaded by right-wing populists to turn their frustration toward outgroups such as immigrants or ethnic minorities.

The effects of Covid-19 could lead to an inversion of these neoliberal norms. As supply lines break down, communities will look to

local and regional producers for their daily needs. When a consumer appliance breaks, people will try to get it repaired rather than buy a new one. Workers, newly unemployed, may turn increasingly to local jobs in smaller companies that serve their community directly.

At the same time, people will increasingly get used to connecting with others through video meetings over the internet, where someone on the other side of the world feels as close as someone across town.

This could be a defining characteristic of the new era. Even while production goes local, we may see a dramatic increase in the globalization of new ideas and ways of thinking—a phenomenon known as “

glocalization.”

Already, scientists are

collaborating around the world in an unprecedented collective effort to find a vaccine; and a globally crowdsourced library is offering a “

Coronavirus Tech Handbook” to collect and distribute the best ideas for responding to the pandemic.

Compassionate community. Rebecca Solnit’s 2009 book, A Paradise Built in Hell, documents how, contrary to popular belief, disasters frequently bring out the best in people, as they reach out and help those in need around them. In the wake of Covid-19, the whole world is reeling from a disaster that affects us all.

The compassionate response Solnit observed in disaster zones has now spread across the planet with a speed matching the virus itself. Mutual aid groups are

forming in communities everywhere to help those in need.

The website

Karunavirus (Karuna is a Sanskrit word for compassion) documents a myriad of everyday acts of heroism, such as the thirty thousand Canadians who have started “

caremongering,” and the mom-and-pop restaurants in Detroit forced to close and

now cooking meals for the homeless.

In the face of disaster, many people are rediscovering that they are far stronger as a community than as isolated individuals. The phrase “social distancing” is helpfully

being recast as “physical distancing” since Covid-19 is bringing people closer together in solidarity than ever before.

Revolution in Values

This rediscovery of the value of community has the potential to be the most important factor of all in shaping the trajectory of the next era. New ideas and political possibilities are critically important, but ultimately an era is defined by its underlying values, on which everything else is built.

The Neoliberal Era was constructed on a myth of the selfish individual as the foundational for values. As Margaret Thatcher

famously declared, “There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.” This belief in the selfish individual has not just been destructive of community—it’s plain wrong.

In fact, from an evolutionary perspective,

a defining characteristic of humanity is our set of prosocial impulses—fairness, altruism, and compassion—that cause us to identify with something larger than our own individual needs. The compassionate responses that have arisen in the wake of the pandemic are heartwarming but not surprising—they are the expected, natural human response to others in need.

Once the crucible of coronavirus begins to cool, and a new sociopolitical order emerges, the larger emergency of climate breakdown and ecological collapse will still be looming over us.

The Neoliberal Era has set civilization’s course directly toward a precipice. If we are truly to “shift course away from our failing trajectory,” the new era must be defined, at its deepest level, not merely by the political or economic choices being made, but by a revolution in values.

It must be an era where the core human values of fairness, mutual aid, and compassion are paramount—extending beyond the local neighborhood to state and national government, to the global community of humans, and ultimately to the community of all life.

If we can

change the basis of our global civilization from one that is wealth-affirming to one that is life-affirming, then we have a chance to create a flourishing future for humanity and the living Earth.

To this extent, the Covid-19 disaster represents an opportunity for the human race—one in which each one of us has a meaningful part to play. We are all inside the crucible right now, and the choices we make over the weeks and months to come will, collectively, determine the shape and defining characteristics of the next era.

However big we’re thinking about the future effects of this pandemic, we can think bigger. As has been said in other settings, but never more to the point: “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.”

.