SUBHEAD: Why the modern office needs a low energy, low tech "retro"lution that includes typewriters.

By Kris De Decker on 22 November 2016 for Low Tech Magazine -

(

http://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2016/11/why-the-office-needs-a-typewriter-revolution.html)

Image above: A Remington Standard #7 typewriter from the 19th century. Remington was a gun manufacturer that turned to office equipment after the civil war when business slowed. From (http://machinesoflovinggrace.com/rems.htm).

Image above: A Remington Standard #7 typewriter from the 19th century. Remington was a gun manufacturer that turned to office equipment after the civil war when business slowed. From (http://machinesoflovinggrace.com/rems.htm).

Digital equipment is one of the main drivers behind the

quickly growing energy use of modern office work. Could we rethink and redesign office equipment, combining the best of mechanical and digital devices?

The Artisanal Office (Antiquity - 1870s)

Office work has accompanied humankind since the formation of social, economic and political organisation and state administration structures, and the functioning of economic trade. The first office institutions were founded in Antiquity, for example in Egypt, Rome, Byzantium, and China.

The period from these early civilizations up to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution was marked by the stability of institutional forms and means of office work. [1] [2]

The bulk of office work involved writing -- copying out letters and documents, adding up columns of figures, computing and sending out bills, keeping accurate records of financial transactions. [3] The only tools were pen and paper -- or rather the quill (the steel pen was invented only in the 1850s) and, before the 1100s in the Western world, stone or clay tablets, papyrus, or parchment.

Consequently, all writing -- and copying -- was done by hand. To copy a document, one simply wrote it again. Sometimes, letters were copied twice: one for the record, and the other to guard against the possibility that the first might get lost. The invention of the printing press in the late middle ages freed scribes from copying books, but the printing press was not suited for copying a few office documents. [4]

Communication was largely human-powered, too, using the feet rather than the hands: people ran around to bring oral or written information from one person to another, either inside buildings or across countries and continents. Finally, all calculating was done in the head, only aided by mathematical charts and tables (which were composed by mental reckoning), or by simple tools like the abacus (not a calculation machine but a memory aid, similar to writing down a calculation).

The Mechanized Office of the Past (1870s - 1950s)

Before the Industrial Revolution, business operated mostly in local or regional markets, and their internal operations were controlled and coordinated through informal communication, principally by word of mouth except when letters were needed to span distances. From the 1840s onwards, the expansion of the railway and telegraph networks in North America encouraged business to grow and serve larger markets, at a time when improvements in manufacturing technology created potential economies of scale. [

5]

Image above: The 19th century office of the accounting department of E. & J. BurkeLtd. in the Times Building, Times Square NYC. From (http://www.officemuseum.com/photo_gallery_1900s_ii.htm).

Image above: The 19th century office of the accounting department of E. & J. BurkeLtd. in the Times Building, Times Square NYC. From (http://www.officemuseum.com/photo_gallery_1900s_ii.htm).

The informal and primarily oral mode of communication broke down and gave way to a complex and extensive formal communication system depending heavily on written documents of various sorts, not just in business but also in government. [

5] Between the 1870s and the 1920s, writing, copying, and other office activities were mechanixed to handle this flow of information.

The birth of office equipment and systematic management was accompanied by three other trends.

The first was the spectacular growth in the number of office workers, mainly women, who would come to operate these machines.

The second was the rise of proper office buildings, which would house the quickly growing number of workers and machines. The third was a division of labor, mirroring the evolution in factories. Instead of performing a diverse set of activities, clerks became responsible for clearly defined sub-activities, such as typing, filing, or mail handling.

This article focuses exclusively on the machinery of office work, and more specifically its evolution in relation to energy use. While it's impossible to write a complete history of the office without taking into account the social and economic context, this narrow focus on machines reveals important issues that have not been dealt with in historical accounts of office work.

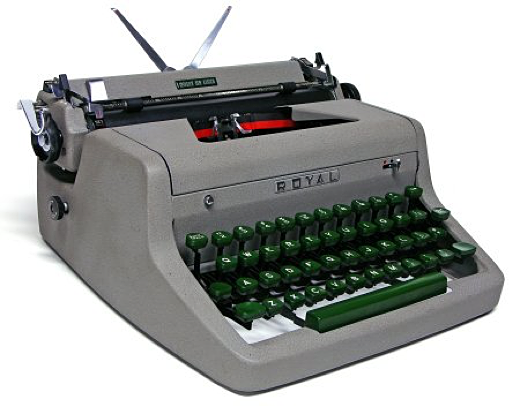

Typewriters

Of central importance in the nineteenth-century information revolution was the typewriter, which appeared in 1874 and became widespread by 1900. (All dates are for the US, where modern office work originated). The "writing machine" made full-time handwriting obsolete. Typing is roughly five times quicker than handwriting and produces uniform text. However, the typewriter's influence went far beyond the writing process itself.

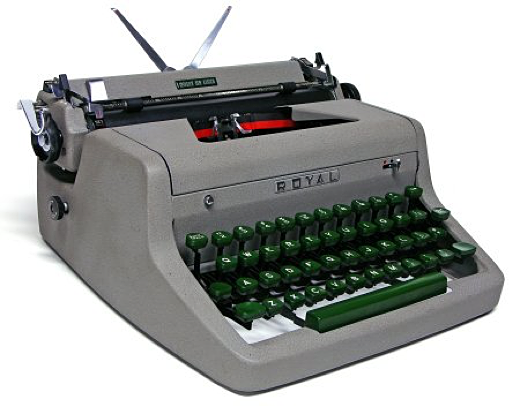

Image above:A 1953 Royal Quiet DeLuxe, the mechanical typewriter at the peak of the that technology. From (Machines of Loving Grace.

Image above:A 1953 Royal Quiet DeLuxe, the mechanical typewriter at the peak of the that technology. From (Machines of Loving Grace.

For copying, an even larger gain in speed was obtained in the combination of the typewriter with carbon paper, an earlier invention from the 19th century. This thin paper, coated with a layer of pigment, was placed in between normal paper sheets.

Unlike a quill or pen, the typewriter provided enough pressure to produce up to 10 copies of a document without the need to type the text more than once. The typewriter was also made compatible with the stencil duplicator, which appeared around the same time and could make a larger number of copies. Considering the importance of writing and copying, the "writing machine" was a true revolution. [4-7]

The typewriter didn't reduce the amount of time that clerks spent writing and copying. Rather, the time spent writing and copying remained the same, while the production of paper documents increased. By the early years of the twentieth century, it became clear that old methods of storing documents -- stacked up in drawers or impaled on spikes -- could not cope with the increasing mounds of papers. This led to the invention of the vertical filing cabinet, which would radically expand the information that could be stored in a given space. [4-8]

Mechanical Calculators

The typewriter quickly evolved into a diverse set of general and special purpose machines, just like the computer would one hundred years later.

There appeared shorthand or stenographic typewriters (which further increased writing speed), book typewriters (which typed on bound books that lay flat when opened), automatic typewriters (which were designed to type form letters controlled by a perforated strip of paper),

ultraportable and pocket typewriters (for writing short letters and notes while on the road), bookkeeping typewriters (which could count and write), and teletypewriters (which could activate another typewriter at a distance through the telegraph network). [4-7] The latter two will be dealt with in more detail below.

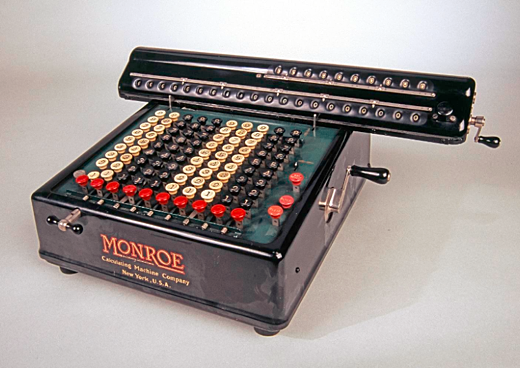

Mechanical

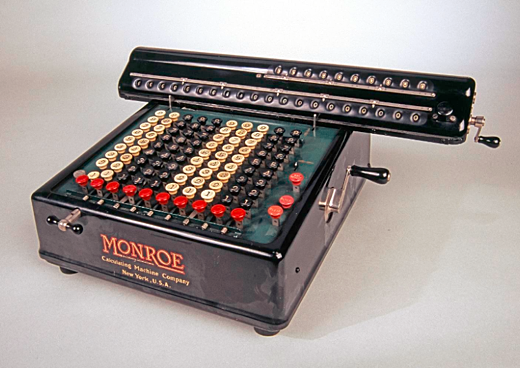

calculating machines were another important tool in the new, mechanised office. "To clerks, mathematical machines are what the rock drill is to the subway labourer", stated an office management manual from 1919. [9] Mechanical calculating machines could add, subtract, multiply and divide through the motion of their parts. Many of these machines had a typewriter-style keyboard with a column for each digit entered (a "full keyboard"). This allowed numbers to be entered more quickly than on a more compact ten-key device, which became common only from the 1950s. [10]

Image above: A 1921 Monroe Model K-20 calculator in the Smithsonian. From Calculating Machine. IslandBreath.org actually purchased one of these K-20 models from Ebay a few years ago.

Image above: A 1921 Monroe Model K-20 calculator in the Smithsonian. From Calculating Machine. IslandBreath.org actually purchased one of these K-20 models from Ebay a few years ago.

Devices designed especially for addition (and sometimes subtraction) were known as adding machines. Adding up long lists of numbers was typical for many business applications, and in mathematical terms many offices didn't need to function at any more sophisticated level.

The first practical adding machine for routine office work -- the Comptometer -- was introduced in 1886. [4][10] At the beginning of the 1900s, the typewriter and the adding machine were combined into the adding typewriter or bookkeeping machine, which became central to the processing of all financial data. [6]

Teletypewriters

Obviously, the telegraph (1840s) and the telephone (1870s) also had an enormous impact on office work. The typewriter, beyond its use in business and government offices, also became an essential machine in telegraph offices. Initially, the telegrapher listened to the Morse sounder and wrote the received messages directly in plain language with a typewriter. [11]

Image above: A relatively late model PDP 8-L teletype machine that has been refurbished. From (https://www.princeton.edu/ssp/joseph-henry-project/pdp-8l/).

Image above: A relatively late model PDP 8-L teletype machine that has been refurbished. From (https://www.princeton.edu/ssp/joseph-henry-project/pdp-8l/).

In the early 1900s, a special typewriter -- the "teletypewriter" or "teletype" -- was designed to transmit and receive telegraphic messages without the need for an operator trained in the Morse code. [12]

When a telegraphist typed a message, the teletypewriter sent electrical impulses to another teletypewriter at the other end of the line, which typed the same message automatically. From the 1920s onwards, teletypewriters became common in the offices of companies, governmental organisations, banks, and press associations. They were used for exchanging data over private networks between different departments of an organisation, a job previously done by messenger boys. [11]

Starting in the 1930s, central switching exchanges were established through which a subscriber could communicate by teletypewriter with any other subscriber to the service, similar to the telephone network but for the purpose of sending text-based messages.

This became the worldwide telex-network, now largely demolished. Telex allowed the instantaneous and synchronous transmission of written messages, like today's chat or email over the internet, or like the exchange of text messages over the mobile phone network (teletypewriters could use the wireless telegraph infrastructure).

Telex was also used for broadcasting news and other information, which was received on print-only teletypewriters. [11]

The office equipment that appeared in the late nineteenth century was in use until the 1970s, when it was replaced by computers.

It is now considered obsolete, but upon a closer look, the superiority of today's computerized machines isn't as obvious as you would think. This is especially true when you take into account the energy that is required to make both alternatives work.

Although it offered spectacular improvements over earlier methods, and although it could perform similar functions as today's digital information technology, much of the office equipment described above remained manually powered for decades. [13]

The first succesful electro-mechanical typewriter -- the IBM Electromatic -- was introduced in 1935, and the breakthrough came only in 1961, with the highly succesful IBM Selectric typewriters.

Unlike a traditional typewriter, this machine used an interchangeable typing element, nicknamed the "golf ball", which spins to the right character and moves across the page as you type. [13][14]

Although electric motors were used on some of the mechanical calculators already in 1901, electrically driven calculators became common only between the 1930s and the 1950s, depending on the type. Pinwheel calculators remained manually operated until their demise in the 1970s. [13]

Unlike typewriters and calculating machines, the telephone and the telegraph could not function without electricity, which forms the basis of their operation.

However, compared to today's communications networks, power use was small: until the late 1950s, almost all routing and switching in the telephone and telegraph infrastructure was done by human operators plugging wires into boards. [11][15]

The Digital Office (1950s - today)

With the arrival of the computer, eventually all office activities became electrically powered. The business computer appeared in the 1950s, although it was not until the mid-1980s that this 'machine' became a common office tool. Reading, writing, copying, data processing, communication, and information storage became totally dependent on electricity.

Screens, printers & scanners

The computer took over the tasks of other machines in the office such as calculating machines, bookkeeping machines, teletypewriters, and vertical filing cabinets. In fact, on the surface, one could say that the computer is the office. After all, its dominant metaphor is taken from office work: it's got a "desktop", "files", "folders", "documents", and a "paper bin". [16]

Furthermore, it can send and receive "mail", make phone calls and accomodate (virtual) face-to-face meetings.

On closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that the arrival of the computer also led to the appearance of new office equipment, which is just as essential to office work as the computer itself. The most important of these devices are printers, scanners, monitors, and new types of computers (data servers, smartphones, tablets). All these machines require electricity.

Monitors and data servers appeared because the computer introduced an alternative information medium to paper, the electronic format.

Welcome to the "Paperless" Office

Printers and scanners appeared because this new medium, contrary to expectations, did not replace the paper format. Although documents can be read, written, transmitted, stored and retrieved in a digital format, in practice both formats are used alongside each other, depending on the task at hand.

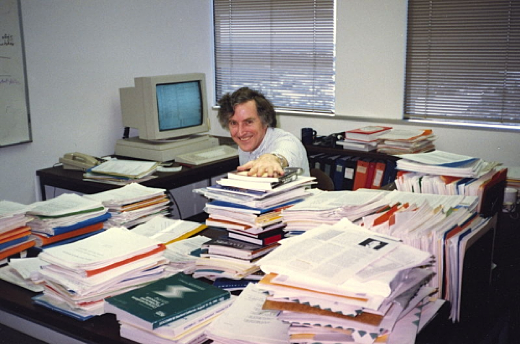

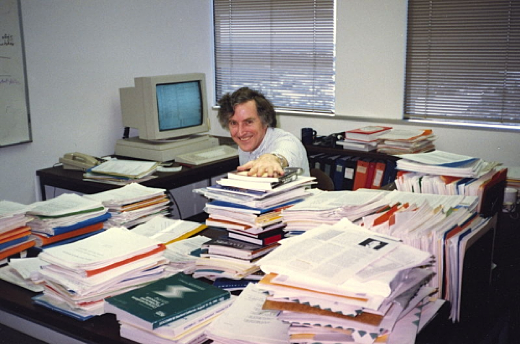

Image above: "Paperless" office in the digital age really means more paper. Computer scientist Bob Braden at his office in 1996. Photo by Carl Malamud.From original article.

Image above: "Paperless" office in the digital age really means more paper. Computer scientist Bob Braden at his office in 1996. Photo by Carl Malamud.From original article.

In spite of the computer, and later the internet, paper has stubbornly remained a key feature of office life. A 2012 study concluded that "most of the offices we visited were more or less full of paper". [17]

This means that the use of resources further increases: to the electricity use of the digital devices, we also have to add the resources involved in making paper.

In their 2002 book The Myth of the Paperless Office, Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper investigate why and how office workers -- especially the growing group of knowledge workers -- are still using paper while new, digital technologies have become so widely available. [8]

They argue that office workers' reluctance to change is not simply a matter of irrational resistance:

"These individuals use paper at certain stages in their work because the technology they are provided with as an alternative does not offer all they need."

Obviously, digital documents have important advantages over paper documents. However, paper documents also have unique advantages, which are all too often ignored.

For example, it was found that office workers actively build up different kinds of paper arrangements on or near their office desks, reminding them of different matters and preparing them for specific tasks.

Computers do not reproduce this kind of physical accumulation. Information exchange, for example in meetings, is another common office practice in which paper is used.

Actions performed in relation to paper are, to a large extent, made visible to one's colleagues, facilitating social interaction. When using a laptop, it's impossible to know what other people in a meeting are looking at. [8] [17]

Most important, however, is the point that paper tends to be the preferred medium for reading documents.

Paper helps reading because it allows quick and flexible navigation through and around documents, reading across more than one document, marking up a document while reading, and interweaving reading and writing -- all important activities of modern knowledge work. [8]

Although some electronic document systems support annotation, this is never as flexible as pen and paper.

Likewise, moving through online documents can be slow and frustrating -- it requires breaking away from ongoing activity, because it relies heavily on visual, spatially constrained cues and one-handed input.

Opening multiple windows on a computer screen doesn't work for back-and-forth cross-referencing of other material during authoring work, both because of slow visual navigation and because of the limited space on the computer screen. [8]

Image above: The multi-screen high-tech office work station. From original article.

Image above: The multi-screen high-tech office work station. From original article.

The use of multiple computer screens (and the use of multiple computers at the same time) is an attempt to overcome the inherent limits of the digital medium and make it more "paper-like".

With multiple screens, it becomes possible to interweave reading and writing, or to read across more than one document. Research has shown that work productivity increases when office workers have access to multiple screens -- a result that mirrors Sellen and Harpers findings about the importance of paper. [18-21]

The use of multiple monitors is rapidly increasing in the workplace, and the increase in "screen real estate" is not limited to two screens per office worker. [19][21]

Fully integrated display sets of twelve individual screens are now selling for around $3,000. [22]

A recent innovation are USB-powered, portable monitors, aimed at travelling knowledge workers but just as handy at the office. Because these monitors have their own set of dedicated hardware, rather than putting all the work of another screen on the computer itself, it's possible to connect up to five portable screens to a laptop. [23]

A multi-touchscreen keyboard, already on the market, could solve the annotation issue.

The Energy Footprint of the Digital Office

The problem with extra screens is that they increase energy use considerably. Adding a second monitor to a laptop roughly doubles its electricity use, adding five portable screens triples it.

A 12-screen display with a suited computer to run it consumes more than 1,000 watt of power. If paper use can be reduced by introducing more and more computer screens, then the lower resource consumption associated with paper will be compensated for with a higher resource consumption for digital devices.

A similar switcheroo happened with information storage and communication. Digital storage saves paper, storage space and transportation, but in order to make digital information readily accessible, dataservers (the filing cabinets of the digital age) have to be fed with energy for 24 hours per day.

And just as the typewriter and carbon paper increased the production of documents, so did the computer.

Especially since the arrival of the internet, people can access more information more easily than ever before, resulting in an increase of both digital and paper documents.

Ever cheaper, faster and better quality printers and copiers -- all digital devices -- keep encouraging the reproduction of paper documents. [8]

The computer increases energy use in many different ways. First of all, digital technology entails extra energy use for cooling -- the main energy use in office buildings.

A 2011 study, which calculated the energy use of two future scenarios, concluded that if the use of digital technology in the office keeps increasing, it would become impossible to design an office building that can be cooled without air-conditioning. [24]

In the "techno-explosion" scenario, all office workers would have two 24'' computer screens, a 27'' touchscreen keyboard, and a tablet. The perhaps extreme scenario also includes one media wall per 20 employees in the office break zone.

On top of operational energy use and cooling comes a higher energy use during the manufacturing phase. The energy used for making a typewriter was spread out over many decades of use. The

energy required for the production of a computer, on the other hand, is a regularly reoccuring cost because computers are replaced every three years or so.

The internet, which has largely engulfed the telephone and telegraph infrastructure, has

become another major source of power demand. The network infrastructure, which takes care of the routing and switching of digital information, uses roughly as much energy as all end-use computers connected to the internet combined.

Learning from the Low Energy Office

The typewriter was just as revolutionary in the 1900s as is the computer today. Both machines transformed the office environment.

However, when we consider energy use, the obvious difference is that the second information revolution was accomplished at much higher costs in terms of energy. So, maybe we should have a good look at pre-digital office equipment and find out what we can learn from it.

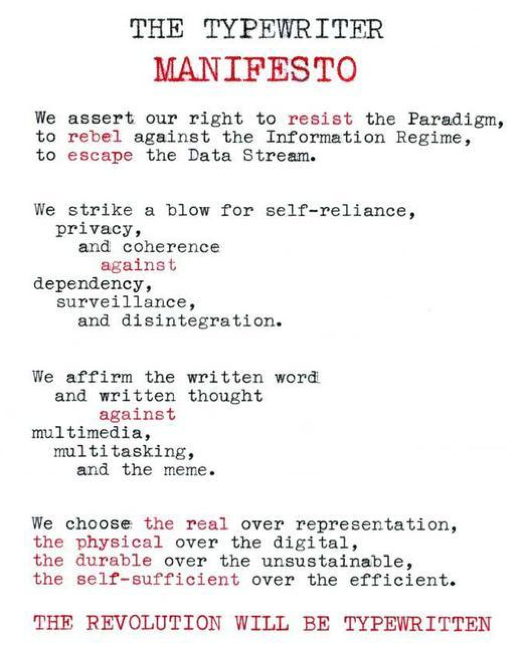

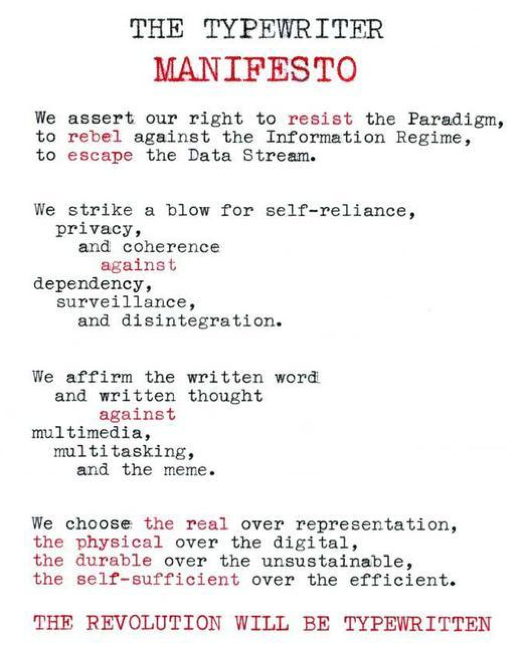

During the last ten years or so, the typewriter has seen a remarkable revival with artists and writers, a trend that was recently documented in The Typewriter Revolution: A typist Companion for the 21st Century (2015). [14]

Like paper, the typewriter has many unique benefits. Obviously, a manual typewriter requires no electricity to operate. If it's built before the 1960s, it's built to outlast a human life.

A typewriter doesn't become obsolete because its operating system is no longer supported, and it can be repaired relatively easily using common tools. If we compare energy input with a simple measure of performance, the typewriter gets a better score than the computer.

There are also practical advantages.

A typewriter is always immediately ready for use. It needs no virus protection or software updates. It can't be hacked or spied upon. Finally, and this is what explains its success with writers and poets: it's a distraction-free, single-purpose machine that forces its user to focus on writing. There are no emails, no news alerts, no chat messages, no search engines and no internet shops.

Image above: The Typewriter Manifesto. From (https://escriturasmecanicas.wordpress.com/2015/05/07/the-typewriter-manifest/).

Image above: The Typewriter Manifesto. From (https://escriturasmecanicas.wordpress.com/2015/05/07/the-typewriter-manifest/).

For office workers, and for knowledge workers in particular, a typewriter could be just as useful as for a poet. Computers may have increased work productivity, but nowadays they are "connected to the biggest engine of distraction ever invented", the internet. [14]

Studies indicate that web web activities are among the main distractions that keep office workers away from productive work. [25][26] Many online applications are especially designed to be addictive. [27]

A typewriter also forces people to write differently, combating distraction within the writing process itself. There is no delete key, no copy-and-paste function. With the computer, editing "became a part of writing from the very start, making the writer ever anxious about anything that just took place". [28]

The typewriter, on the other hand, forces the writer to think out sentences carefully before committing them to paper, and to keep going forward instead of rewriting what was already written. [14]

The "Back-in-Time" Sustainable Office

How can we insert the common sense of the typewriter -- and other pre-digital equipment -- into the modern office?

Basically, there are three strategies. The most radical is to replace all our digital devices by mechanical ones, and replace all dataservers with paper stacked in vertical filing cabinets, in other words we could go back in time.

This would surely lower energy use, and it's the most resilient option: for all their wonders, computers serve absolutely no purpose when there's no electricity.

Nevertheless, this is not an optimal strategy, because we would lose all the good things that the computer has to offer. "The enemy isn't computers themselves: it's an all-embracing, exclusive computing mentality", writes Richard Polt in The Typewriter Revolution. [14]

Another strategy is to use mechanical office equipment alongside digital office equipment. There's some potential for energy reduction in the combined use of both technologies. For interweaving reading and writing, the typewriter could be used for writing and the computer screen for reading, which saves an extra screen and a printer.

A typewriter could also be combined with a low energy tablet instead of a laptop or desktop computer, because in this configuration the computer's keyboard is less important.

Once finished, or once ready for final editing in a digital format, a typewritten text can be transferred to a computer by scanning the typewritten pages.

The actual typewritten text can be displayed as an image ("typecasting"), or it can be scanned with optical recognition software (ORC), which converts typewritten text into a digital format. This process implies the use a scanner or a digital camera, however these devices use much less energy than a printer, a second screen, or a laptop.

By reintroducing the typewriter into the digital office, the use of the computer could thus be reduced in time, while the 'need' for a second screen disappears.

The Sustainable Office of the Future

The third strategy is to rethink and redesign office equipment, combining the best of mechanical and digital devices. This would be the most intelligent strategy, because it offers a high degree of sustainability and resilience while keeping as much of the digital accomplishments as possible.

Such a low-tech office requires a redesign of office equipment, and could be combined with a

low-tech internet and

electricity infrastructure.

E-Typewriters

For low-tech writing, a couple of devices are available. A first example is the Freewrite, a machine that came on the market earlier this year after a succesful crowdfunding campaign. [29]

Image above: The low-tech electric writing machine Freewrite. From original article.

Image above: The low-tech electric writing machine Freewrite. From original article.

Like a typewriter, it's a distraction-free machine that can only be used to write on, and that's always instantly ready to be used.

Unlike a typewriter, however, it has a 5.5'' e-paper screen, it can store a million pages, and it offers a WiFi-connection for cloud-backups. Files are saved in plain text format for maximum reliability, minimal file size, and longest anticipated support.

Apart from a backspace key, there is no way to navigate through the text, and the small screen only displays ten lines of text. Drafting and editing have been separated with the intent to force the writer to keep going. For editing or printing, the text is then transferred to a computer using the WiFi connection.

The device is stated to have a "4+ week battery life with typical usage", which is defined as half an hour of writing each day with WiFi turned off. That's a strange way to communicate that the machine runs 14 hours on one battery charge, and when I asked the makers how much power it needs they answered that they "don't communicate this information".

Nevertheless, enabling 14 hours of writing already beats the potential of the average laptop by a factor of three.

Hardware Word Processors

Another type of digital typewriter is the hardware word processor. Before word processing became software on a personal computer in the 1980s, the word processor was a stand-alone device. Like a typewriter, a hardware word processor is only useful to write on, but it has the added capability of editing the text before printing.

Although hardware word processors work and look like computers, they are non-programmable, single-purpose devices. [30] [31]

The great advantage of a hardware word processor is that both writing and editing can happen on the same machine -- a typewriter or a machine like the Freewrite requires another machine to do the editing (unless you write multiple versions of the same text).

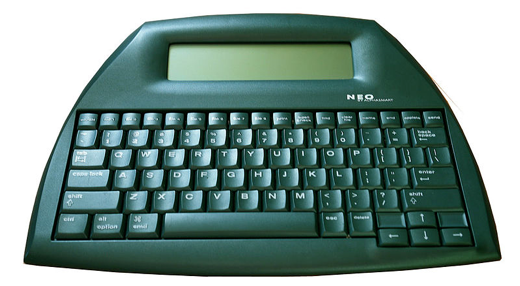

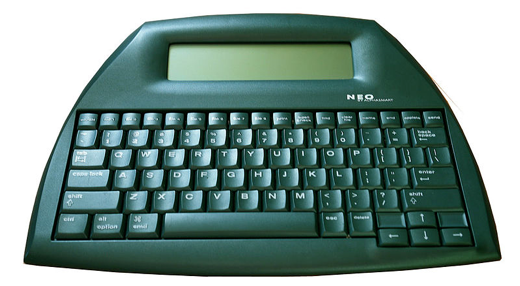

The hardware word processor virtually disappeared when the general-purpose computer appeared. One notable exception is the Alphasmart, which was produced from 1992 until 2013.

This rugged portable machine is still widely traded on the internet and developed a cult following, especially among writers. The Alphasmart was conceived as an affordable computer for schools, but the low price was not its only appeal.

The machine responded to the need for a tool that would make kids concentrate on writing, and not on editing or formatting text. Although it has full editing capabilities, the small screen (showing 6 lines in the latest model) invites writing rather than excessive editing. [32][33]

Image above: AlphaSmart From ().

Image above: AlphaSmart From ().

The Alphasmart is especially notable for its energy efficiency, using as little electricity as an electronic calculator. The latest model could run for more than 700 hours on just three AA-batteries, which corresponds to a power use of 0.01 watt.

The machine has a full-sized keyboard but a small, electronic calculator-like display screen, which requires little electricity. It has limited memory and goes into sleep-mode between keystrokes.

The Alphasmart can be connected directly to a printer via a USB-cable, bypassing a computer entirely if the aim is to produce a paper document. Transferring texts to the computer for digital transmission, storage or further editing also happens via cable. [32][33]

Interestingly, Alphasmart released a more high-tech version of the device in 2002, the Alphasmart Dana. It was equipped with WiFi for transmitting documents, it had 40 times more memory than its predecessor, and it featured a touchscreen.

The result was that battery life dropped twentyfold to 25 hours, clearly showing how quickly the energy use of digital technology can spiral out of control -- although even this machine still used only 0.14 watts of power, roughly 100 times less than the average laptop. [32][33]

Of course, a low-tech office doesn't exclude a real computer, a device that does it all. A small tablet with a wireless keyboard can be operated for as little as 3W of electricity and many of the capabilities of a laptop (including the distractions).

An alternative to the use of a tablet is a Raspberry Pi computer, combined with a portable USB-screen. Depending on the model, a Raspberry Pi draws 0.5 to 2.5 watts of power, with an extra 6 or 7 watts for the screen.

A Pi can serve as a fully functional computer with internet access, but it's also very well suited for a single-purpose, distraction-less word processing machine without internet access. Such machines could be powered with a solar system small enough to fit on the corner of a desk.

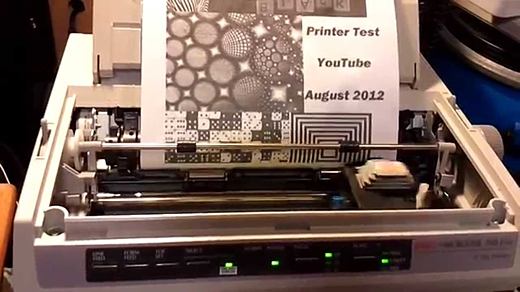

Dot-Matrix Printers

Unless we revert to the typewriter, the office also needs a more sustainable way of printing. Since the 1980s, most printing in offices is done with a laser printer. These machines require a lot of energy: even when we take into account their higher printing speed, a laser printer uses 10 to 20 times as much electricity than a inkjet printer. [34]

Unfortunately, inkjet printers are much more expensive to use because the industry makes a profit by selling overpriced ink cartridges.

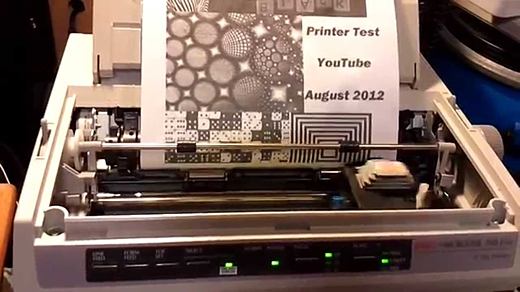

Until the arrival of the laser printer, all printing in offices was done by dot-matrixprinters. Their power use and printing speed is comparable to that of inkjetprinters, but they are much cheaper to use -- in fact, it's the cheapest printing technology available.

Like a typewriter, a dot-matrix printer is an impact printer that makes use of an ink ribbon. These ribbons are sold as commodities and cost very little. Unlike a typewriter, the individual characters of a matrix printer are composed of small dots.

Image above: A modern and efficient Oki dot-matrix electronic printer. From (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3NkITEI3Jg).

Image above: A modern and efficient Oki dot-matrix electronic printer. From (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3NkITEI3Jg).

Dot-matrix printers are still for sale, for applications where printing costs are critical. Although they're not suited for printing images or colors, they are perfect for the printing of text.

They are relatively noisy, which is why they were sometimes placed under a sound-absorbing hood. There is no practical low-tech alternative for the copier machine, which only appeared in the 1950s.

However, since a photocopier is a combination of a scanner and a laserprinter, the copying of paper documents could happen by using a combination of a computer with a scanner and a dot-matrix or inkjet printer.

The information society promises to dematerialize society and make it more sustainable, but modern office and knowledge work has itself become a large and rapidly

growing consumer of energy and other resources.

Choosing low-tech office equipment would be a great start to address this problem. Such a strategy is especially significant in that the energy use goes far beyond the operational electricity use on-site.

Sources:

[1]

Evolution of the office building in the course of the 20th century: Towards an intelligent building, Elzbieta Niezabitowska & Dorota Winnicka-Jaskowska, in Intelligent Buildings International, 3:4, 238-249, 2011.

[2]

Economy and Society, Max Weber, 1922.

[3]

Woman's place is at the typewriter, Margery W. Davies, 1982. Quoted by the

Early Office Museum.

[4]

Machines in the Office

, Rodney Dale and Rebecca Weaver, 1993.

[5]

Control through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management (Studies in Industry and Society)

, JoAnne Yates, 1989

[6]

Innovation Junctions: Office Technologies in the Netherlands, 1880-1980 (PDF), Onno de Wit, Jan van den Ende, Johan Schot and Ellen van Oost, in Technology and Culture, Vol. 43, No. 1 (Jan., 2002), pp. 50-72

[7]

Early Office Museum, website.

[8]

The Myth of the Paperless Office (MIT Press)

, Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper, 2003.

[9]

Office Management, Geoffrey S. Childs, Edwin J. Clapp, Bernard Lichtenberg, 1919.

[10]

Calculating Machines,

Adding Machines. Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

[11]

The Myth of the Paperless Office (MIT Press)

, Anton A. Huurdeman, 2003.

[12]

Teleprinter, Encyclopedia Britannica.

[13] Nobody seems to have researched the energy use of pre-digital office equipment, so this information is partly derived from an online search through the databases of eBay, the

Smithsonian Institution, and the

Early Office Museum, and partly on fragmentary information from secondary sources. For example, a

1949 survey of the equipment in high school office machine courses in the state of Massachussetts shows that the majority of typewriters, calculators, adding machines, duplicators and addressing machines were manually operated, although most of these machines were less than 10 years old.

[14]

The Typewriter Revolution: A Typist's Companion for the 21st Century

, Richard Polt, 2015

[15]

Gift of Fire, A: Social, Legal, and Ethical Issues in Computing

, Sara Baase, 1997

[16]

How the computer changed the office forever, BBC News, August 2013.

[17]

Mundane Materials at Work: Paper in Practice, Sari Yli-Kauhaluoma, Mika Pantzar and Sammy Toyoki, Third International Symposium on Process Organization Studies, Corfu, Greece, 16-18 June, 2011.

[18]

Productivity and multi-screen computer displays (PDF), Janet Colvin, Nancy Tobler, James A. Anderson, Rocky Mountain Communication Review, Volume 2:1, Summer 2004, Pages 31-53.

[19]

Evaluating user expectations for widescreen content layout (PDF), Joseph H. Goldberg & Jonathan Helfman, Oracle, 2007

[20]

Are two monitors better than one?, J.W: Owens, J. Teves, B. Nguyen, A. Smith, M.C. Phelps, Software Usability Research Laboratory, August 2012

[21]

Are two better than one? A comparison between single and dual monitor work stations in productivity and user's windows management style. Chen Ling, Alex Stegman, Chintan Barhbaya, Randa Shehab, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, September 2016

[22]

http://www.multi-monitors.com/Twelve_Monitor_Display_Arrays_s/53748.htm

[23]

The best USB-powered portable monitors, Nerd Techy, 2016

[24]

Trends in office internal gains and the impact on space heating and cooling (PDF), James Johnston et. al, CIBSE Technical Symposium, September 2011

[25]

Employees waste 759 hours each year due to workplace distractions, The Telegraph, June 2015

[26]

Internet Addiction: A New Clinical Phenomenon and Its Consequences (PDF), Kimberly S. Young, American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 48 No.4, December 2004.

[27]

The Binge Breaker, The Atlantic, November 2016.

[28]

The future of writing looks like the past, Ian Bogost, The Atlantic, May 2016.

[29]

Freewrite, website.

[30]

Word Processing (History of) (PDF), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Vol. 49, pp. 268-78, 1992.

[31]

A brief history of word processing (through 1986), Brian Kunde.

[32]

AlphaSmart: a history of one of Ed-Tech's Favorite (Drop-Kickable) Writing tools, Audrey Watters, Hackeducation, July 2015.

[33]

AlphaSmart: Providing a Smart Solution for one Classroom-Computing "Job" (PDF), James Sloan, Inno Sight Institute, April 2012.

[34]

Zeven instap zwart-wit laserprinters vergelijktest, Hardware.info, December 2014. The data were corrected for the higher printing speed of the laser printer.

, Rodney Dale and Rebecca Weaver, 1993.

, Rodney Dale and Rebecca Weaver, 1993. , JoAnne Yates, 1989

, JoAnne Yates, 1989  , Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper, 2003.

, Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper, 2003. , Richard Polt, 2015

, Richard Polt, 2015 , Sara Baase, 1997

, Sara Baase, 1997