SUBHEAD: Disappointments to my inner Neanderthal, who, wrinkling his jutting brow, mutters, What’s next?

By Brian Miller on 23 July 2017 for Winged Elm Farm -

(http://www.wingedelmfarm.com/blog/2017/07/23/on-becoming-an-evolutionary-cul-de-sac/)

Image above: Chain drum lifter rated for 2,000pound loads available from Amazon.com available for under $100. From (https://www.amazon.com/Vestil-CDL-2000-Chain-Lifter-Capacity/dp/B002KLJUSK).

I was 16 when I put brand new brakes on my car. It took most of an afternoon, and it was a task that finally completed gave me a real sense of accomplishment. True, I had a couple of small parts left over. But I was young and I operated under the assumption that the auto parts store had given me either spares or parts that didn’t go with my model.

Once finished, I climbed in the driver’s seat, turned the ignition, and took off down the road. Wow! It was a smooth ride and I felt great. That is, until I came up fast to my first stop sign and applied the brakes.

Odd feeling, pushing down on the brake pedal at 50 miles an hour and encountering no resistance. It’s a memory I can still summon readily to this day. Fortunate for me, the auto engineers had built in a backup breaking mechanism called the emergency brake, a handy invention that I deduced might be best to deploy … quickly.

I give you this preamble as evidence that even though a person comes from solid civil engineering stock, basic mechanical skill is not an inherited gene. We all have the friend, often on speed dial, who is great at teasing out the workings of ‘most any thingamajig.

But my solutions to mechanical failures are victories hard won. The puzzles that five-year-olds routinely solve on Facebook in a cute two minutes elude me — sometimes for hours, and sometimes for many years.

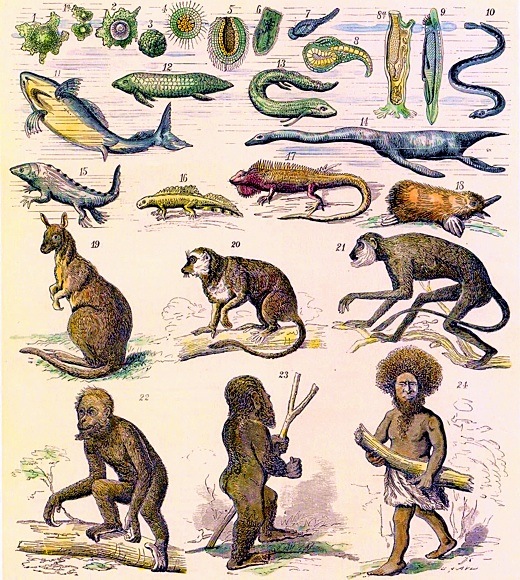

The Neanderthals who lurk in my ancestry were a smartish but conservative group of bipeds. They developed a reliable tool kit over the millennia to make their lives run smoother. But then they apparently had a community meeting and said,

Enough is enough, and they settled in for the next 100,000 years and made no new improvements. I kind of admire that about them; perhaps we could learn a thing or two from that approach to technology.

But then there is my H. sapiens DNA. It allows me, eventually, to not only see a solution but also want to implement it.

Yesterday, for instance, we were unloading 55-gallon-drum feed barrels. Cindy backed up the tractor and boom pole to the bed of the truck. Dangling from the boom pole was a nifty contraption called a barrel lifter.

This simple invention is the best $40 we ever spent. It has two metal “hands” at the end of a chain that grab the edge of the barrel. Once the boom pole is raised, the barrel lifter and barrel in tow swing up and out of the truck bed. No muscling required.

The first barrel was a breeze. The second barrel presented a slight problem. It didn’t completely clear the bed of the truck. Taking on my finest Thinker pose, I struggled for a solution. After some minutes, the little gray cells began to sing: It’s the weight, I deduced triumphantly!

Each 300-pound feed barrel removed took more weight off the truck suspension, thereby raising the bed of the truck a couple of inches and causing each subsequent barrel to drag along the tailgate when hoisted. But voilà!

A few adjustments to the tractor’s three-point hitch, which in turn shortened the top link’s angle after each barrel, gave the boom pole a higher lift. Problem solved.

This Eureka moment may not mean much to you engineering types. But small successes like this one are huge to my sapiens self. Victories for H. sapiens, yet disappointments to my inner Neanderthal, who, wrinkling his jutting brow, mutters, What’s next? Will he be wanting to invent block and tackle?

Perhaps. But I must leave that astonishing accomplishment for later. I’ve just had a brain flash that there just might be a better way to knap flint! Stay tuned.

.

By Brian Miller on 23 July 2017 for Winged Elm Farm -

(http://www.wingedelmfarm.com/blog/2017/07/23/on-becoming-an-evolutionary-cul-de-sac/)

Image above: Chain drum lifter rated for 2,000pound loads available from Amazon.com available for under $100. From (https://www.amazon.com/Vestil-CDL-2000-Chain-Lifter-Capacity/dp/B002KLJUSK).

I was 16 when I put brand new brakes on my car. It took most of an afternoon, and it was a task that finally completed gave me a real sense of accomplishment. True, I had a couple of small parts left over. But I was young and I operated under the assumption that the auto parts store had given me either spares or parts that didn’t go with my model.

Once finished, I climbed in the driver’s seat, turned the ignition, and took off down the road. Wow! It was a smooth ride and I felt great. That is, until I came up fast to my first stop sign and applied the brakes.

Odd feeling, pushing down on the brake pedal at 50 miles an hour and encountering no resistance. It’s a memory I can still summon readily to this day. Fortunate for me, the auto engineers had built in a backup breaking mechanism called the emergency brake, a handy invention that I deduced might be best to deploy … quickly.

I give you this preamble as evidence that even though a person comes from solid civil engineering stock, basic mechanical skill is not an inherited gene. We all have the friend, often on speed dial, who is great at teasing out the workings of ‘most any thingamajig.

But my solutions to mechanical failures are victories hard won. The puzzles that five-year-olds routinely solve on Facebook in a cute two minutes elude me — sometimes for hours, and sometimes for many years.

The Neanderthals who lurk in my ancestry were a smartish but conservative group of bipeds. They developed a reliable tool kit over the millennia to make their lives run smoother. But then they apparently had a community meeting and said,

Enough is enough, and they settled in for the next 100,000 years and made no new improvements. I kind of admire that about them; perhaps we could learn a thing or two from that approach to technology.

But then there is my H. sapiens DNA. It allows me, eventually, to not only see a solution but also want to implement it.

Yesterday, for instance, we were unloading 55-gallon-drum feed barrels. Cindy backed up the tractor and boom pole to the bed of the truck. Dangling from the boom pole was a nifty contraption called a barrel lifter.

This simple invention is the best $40 we ever spent. It has two metal “hands” at the end of a chain that grab the edge of the barrel. Once the boom pole is raised, the barrel lifter and barrel in tow swing up and out of the truck bed. No muscling required.

The first barrel was a breeze. The second barrel presented a slight problem. It didn’t completely clear the bed of the truck. Taking on my finest Thinker pose, I struggled for a solution. After some minutes, the little gray cells began to sing: It’s the weight, I deduced triumphantly!

Each 300-pound feed barrel removed took more weight off the truck suspension, thereby raising the bed of the truck a couple of inches and causing each subsequent barrel to drag along the tailgate when hoisted. But voilà!

A few adjustments to the tractor’s three-point hitch, which in turn shortened the top link’s angle after each barrel, gave the boom pole a higher lift. Problem solved.

This Eureka moment may not mean much to you engineering types. But small successes like this one are huge to my sapiens self. Victories for H. sapiens, yet disappointments to my inner Neanderthal, who, wrinkling his jutting brow, mutters, What’s next? Will he be wanting to invent block and tackle?

Perhaps. But I must leave that astonishing accomplishment for later. I’ve just had a brain flash that there just might be a better way to knap flint! Stay tuned.

.