SUBHEAD: Designing our orchards for economic collapse and climate-destabilization.

By Dan Allen on 4 November 2013 for Resilience.org-

(

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2013-11-04/growing-fruit-in-a-nuthouse-designing-our-orchards-for-economic-collapse-and-climate-destabilization)

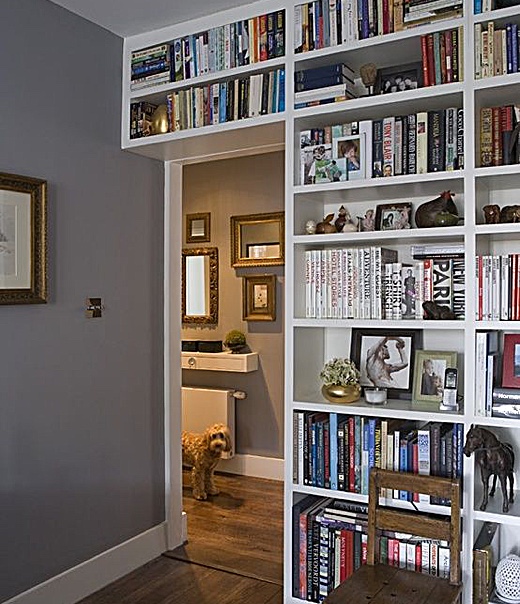

Image above: A Medium sized oarchard farm with a variety of species. From original article.

Image above: A Medium sized oarchard farm with a variety of species. From original article.

“Historians who look back on these strange years of suspended consequence will marvel at how this empire of grift kept its [economic] wheels turning after its engine died. …You can be sure there will be a snapback from all this drift and anomie, and when it comes, the snap will be savage. …Then gird your loins for the new age of consequence.” – James Kunstler

“The garden lives by the immortal Wheel

That turns in place, year after year, to heal

It whole. Unlike our economic pyre

That draws from ancient rock a fossil fire,

An anti-life of radiance and fume

That burns as power and remains as doom,

The garden delves no deeper than its roots

And lifts no higher than its leaves and fruit.”

Wendell Berry (in Leavings, 2010)

“I see a million hills green with crop-yielding trees and a million neat farm homes snuggled in the hills. These beautiful tree farms hold the hills from Boston to Austin to DesMoines. The hills of my vision have farming that fits them and replaces the poor pasture, the gullies, and the abandoned lands that characterize today so large a part of these hills.” -- J. Russell Smith (in Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, 1950)

SUMMARY:

As the industrial economy collapses and the earth’s climate destabilizes, we are entering the Age of Consequence. Agriculture as we have known it will no longer be a given. We will need to lean heavily on perennial crops such as fruit and nut trees. But how can we increase the chances of getting a living baseline yield from these orchards? Plant standard-sized trees in a diverse mixed species orchard, with a high level of genetic diversity within each species. Only a true partnership with the land has a shot at getting us through the coming economic and climatic maelstrom.

I. THE IMPERATIVE OF ECOLOGICAL AGRICULTURE

Friends and neighbors, we have sinned. Oh, have we sinned!!

And so having sinned, our bloated and disintegrating human caravan now careens headlong into the Age of Consequence.

And in this coming Age of Consequence, certain activities that we have pretended to be optional will reveal themselves as emphatically not optional. One of these activities is the way we obtain our food.

Let me explain:

Taking the long view as a species, we certainly should seek to end the destructive spiral of annual agriculture. It’s an ecocidal program with a 10,000 year history of abject ecological and social ruin. It unavoidably diminishes the land and local human communities over time, and has been the germ of ultimate collapse for any civilization that has practiced it. If you’d like details, see David Montgomery’s Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (2012).

And taking the somewhat-shorter long-view, we certainly should seek to end the war-like assaults on the biosphere by the industrial versions of both annual and perennial agriculture. With their entropic floods of fossil energy, both versions of industrial agriculture have a 70-year track record of utter devastation at a pace and scale orders of magnitude greater than ever witnessed in the already-sordid history of human agriculture. If you’d like details, see Andrew Kimbrell’s (ed.) Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture (2002).

But looking even a short distance into the future, we find that we simply cannot go on as we have. The economic and climatic maelstroms bearing down on us will likely overwhelm any attempts to coerce food from the land in the same ham-handed, ecologically-ignorant ways as our earth-tilling and oil-swilling predecessors. We flat out will not be able to perpetrate the industrial versions of either annual or perennial agriculture – and perhaps even any form of annual agriculture.

Indeed, obtaining food in both the short and long term futures promises to be a damn tricky proposition. And thus will we need help. And that help, if it comes at all, must come from the land. If we are to have any chance of survival, we will need to intertwine our lives and cultures once again with the land. We will need to live an agriculture that ‘behaves’ – that sails with the complex ecological currents of our climatically-buffeted, economically-turbulent future.

For while the path of ecological agriculture has always been the wise one, as a species fighting for survival in a world spiraling to ruin, the luxury of choosing the wrong option has expired. We must reform way we grow food. We must fashion a more resilient agriculture within the limitations of the climatic, economic, energetic, social, and ecological maelstroms bearing down on us.

…Or else.

II. MIXED ORCHARDS IN THE AGE OF CONSEQUENCE

“In the year 1860…we were confronted with the worst drought that was ever known in Kansas. It continued about eighteen months. The Neosho river dried up…[and] no farm products had been raised in the country. Settlers were in a starving condition. A good many people left the country. …Providentially there was one of the greatest pawpaw and nut crops ever known to the Neosho bottoms. ….[A] great many of the settlers subsisted on pecan nuts and pawpaws.” – James A. Little (in The Pawpaw, 1905)

I have written previously on the sorts of changes we must make in our agriculture to address the mounting challenges of the not-too-distant future. For details, see the two-part essay at

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2013-03-11/when-agriculture-stops-working-a-guide-to-growing-food-in-the-age-of-climate-destabilization-and-civilization-collapse.

In a nutshell, agriculture, as we have practiced it, will no longer be a given. Due to accelerating economic collapse and mounting climate destabilization, we will fairly shortly need to change the way we get our food. We’ll need an agriculture (1) conducted at a finer scale, where attention to detail and place-based differences replaces industrial uniformity, (2) where human labor and ecological knowledge replace fossil-fuel-powered technology, and (3) where polycultures of perennial vegetation replace the annual monocultures of today.

In this essay I just want to get a little more specific about a key element of this more resilient form of agriculture – the mixed-species fruit and nut orchard.

I think such specificity is important because (1) the people planting these orchards will need some guidance, as many will be returning, pale and bleary-eyed, from the magical realm of cyberspace, (2) these orchards need to be planted now in order to be productive when we will need them, and (3) the ready availability of diverse fruit and nut genetics (via long-distance travel and mail service) will likely collapse along with the industrial economy in short order.

I’ll start by (1) addressing the coming climatic and economic predicaments most limiting to these orchards, then (2) detail the key characteristics needed to address these limitations, and finally, (3) give an example of a representative orchard suitable to central NJ, where I live.

III. COMING CLIMATE-DESTABILIZATION PROBLEMS IN THE ORCHARD

“The word drought doesn’t really capture what’s happening in Texas. …Instead of rain, spring brought nearly half a million acres of wildfires.” – NPR report (quoted in How Bad is the Texas Drought? “In Austin, They are Praying for a Hurricane”)

So what sorts of problems will the planet’s accelerating climatic destabilization bring to our fruit and nut orchards in the US? Oh boy

! Lots and lots of problems!

See the chart below for an outline of the most significant climate-related limitations for the orchards of the future. And think of the following climatic limitations in two ways: (1) as reasons why the current industrial orchard systems will fail in the coming years, and (2) as unavoidable limitations that a more resilient post-industrial orchard system should be designed to address.

Figure 1: Limitations faced by US orchards under climate destabilization.

IV. COMING ECONOMIC COLLAPSE PROBLEMS IN THE ORCHARD

“The biggest bubble we now face is one of confidence. …In the ability of the [current economic] system to carry on as it has been and to recover further from here. If that bursts – when that bursts – there will be a colossal rush for the exits that will make the liquidity crunch of 2008 look like a cuddle party.” – Chris Martenson (http://www.peakprosperity.com/insider/83348/cuff-tarnishing-american-exceptionalism)

And what sorts of problems will the accelerating US and global economic collapse bring to US orchards?

Oh boy! Lots and lots of problems!

See the chart below for an outline of the most significant economic-related limitations for the orchards of the future. And again, think of the following limitations in two ways:

- Reasons why the current industrial orchard systems will fail in the coming years, and

- Unavoidable limitations that a more resilient post-industrial orchard system should be designed to address.

Figure 2: Limitations faced by US orchards under economic collapse.

V. KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ORCHARDS WE NEED TO PLANT

“Trees are Salvation.” – E.F. Schumacher

Ok. So we’ve discussed our prime directive for these orchards: partnership with the land. And we’ve discussed the climatic and economic limitations such orchards will face. …So now, what exactly do we

do? What should we plant? How should we configure the plants? How should we manage them? How do we get started? When should we get started?

Good questions, all. Below are perhaps the beginnings to some of the possible answers.

But before I make these suggestions, let me offer this qualification: I make no claims to be an uber-orchardist. I started planting my several hundred fruit and nut trees 15 years ago, and have watched them carefully. I have some ideas on what sorts of things have worked and what have not worked for my trees. I plant more every year; I learn more every year; I make adjustments every year.

I’ve also read some damn good books to supplement my experience (J. Russell Smith, Mark Shepard, Wes Jackson, Wendell Berry, Gene Logsdon, Aldo Leopold, as well as a good bit of the extensive permaculture and ecology literature). I am also a Ph.D. chemist with a fairly sound understanding of the physical, biological, and earth sciences.

So, qualifications aside, here are my humble suggestions for (dun-dun-duuuuuuun)

The Orcharrrrrrrds of Tomorrowwwwww!!

1. STANDARD-SIZED (NON-DWARF) TREES:

Plant larger, standard-sized fruit & nut trees – not the grafted dwarf or semi-dwarf versions.

Why? To address wind, drought, deluge, nutrients, evacuations, & theft. Explanation: While the standard-sized trees take longer to reach maturity, the larger root systems of the standard-sized trees

- provide for more stability in fierce winds,

- explore a deeper and wider region of the soil profile to reach more soil nutrients,

- have better access to scarce soil water during droughts,

- and hold the soil better during soil-gouging deluges with both their extensive roots and drop-slowing canopies.

In addition, if you need to abandon a standard-tree orchard for a few years, the trees will be mostly fine when you return. Try the same thing with a dwarf orchard and most of the trees will be dead or toppled when you return. And it’s also a heck of a lot harder to steal a large amount of fruit and nuts from a standard-sized orchard in a single night – try it sometime.

2. TREE DIVERSITY ACROSS FAMILIES, GENERA, & SPECIES:

Plant a diverse mix of tree families, genera, and species in the orchard.

Why? To address drought, wetness, heat, cold, frost, pests, nutrients, labor, theft, & evacuations. Explanation: The planting of a truly mixed-species orchard (e.g., apples, chestnuts, persimmon, pecans, peaches, hickories, pawpaws, etc., etc.) seems, at first blush, like it would introduce a host of logistical problems. But when divorced from the industrial model, these ‘problems’ actually become crucial advantages.

Different species have different tolerances to the more unpredictable and more intense weather extremes we can expect – drought, prolonged wetness, late frosts, intense summer heat, and intense winter cold. Thus, a diverse mix of species will increase the odds that a fair percentage of the orchard will produce a yield every single year. And it’s this reliability of a baseline annual yield from the orchard that will become much more important to our survival in the trying years ahead than some narrowly-maximized total yield.

Losses due to pests will also be ameliorated due to (1) the improbability of many tree species suffering pest outbreaks in the same year, and (2) the inability of pest densities to rise too high due to the lower density of any one tree species, and (3) an additional checking of pest densities due to a richer, more diverse orchard ecosystem that can provide habitat to predators of those pests.

The necessity of both nutrient and irrigation inputs would also be lessened since the wide variety of root architecture and patterns of nutrient uptake of the different species will (1) lessen competition between orchard trees, and (2) allow a more efficient use of both existing and added soil nutrients. By the same token, severe droughts will be less problematic as competition for soil moisture is decreased, and the presence of some very-deep-rooted trees will lessen the chances of a total crop failure.

Furthermore, a truly mixed-species orchard greatly eases the labor requirements of the orchard. The maintenance and harvest windows will be spread out more thinly over many months, rather than having them concentrated in a few brutally-difficult, nail-biting weeks. This ‘spreading out’ of labor requirements will allow a family or small community to tend a much larger acreage than if the orchard consisted of just a few species.

Energy and material requirements for processing and storage are also lessened when the pulses of harvested produce are smaller in magnitude. This will allow such operations to be handled by small-scale contemporary solar, wind, or hydro energy sources, as well as a much-reduced (and more easily maintained) processing infrastructure.

Tree diversity also lessens the risk of catastrophic losses due to theft, since there won’t be too much available to steal at any given time. Temporary evacuations are also less problematic since the long harvest window lessens the chances of losing the entire harvest due to absence.

3. GENETIC DIVERSITY WITHIN EACH SPECIES:

3. GENETIC DIVERSITY WITHIN EACH SPECIES:

Plant a diverse mix of varieties of each tree species within the orchard, including trees grown from seed, rather than just a few high-yielding grafted cultivars.

Why? To address drought, winds, heat, cold, frost, labor, & theft. Explanation: While resisting the temptation to plant only the handful of highest-yielding cultivars of every species will result in a lower maximum yield – that’s not the yield we’re aiming for! Again, we need to increase the chances of a reliable baseline yield from the orchard in the face of a host of unpredictable climatic and economic troubles. And planting a large variety of both grafted cultivars and seedling trees will help accomplish this in several ways:

Large genetic differences between different varieties of the same species can provide a range of genetic ‘talents’ that can greatly reduce the probability of complete crop failure in any given year. These genetic differences include (1) a range of drought, wetness, heat, cold, and wind tolerances, (2) widely varying pollination windows, which are quite vulnerable to wacky weather and are often the crucial factor in yield on a given year, and (3) differing vulnerability to a given pest outbreak.

Different varieties can also spread out the harvest window, resulting in (1) an easing of the labor, energy, and infrastructure requirements, (2) reduced likelihood of large loss due to theft, and (3) a reduced probability of missing the smaller harvest window due to a forced absence from the farm. Anybody who has at least two apple trees knows they ripen at different times – sometimes by months!

We can no longer count on industrial petrochemicals and fossil energy to protect our genetically-narrow (and thus pitifully-vulnerable) orchards from the rest of the biosphere. We need orchards that can take care of themselves, and we need to allow them the genetic diversity to figure it out. We need to stop telling the trees exactly what to do – we’re no damn good at it! We need to let them tell us what they need, and then work with them to make sure they get it. If they need seedling-tree genetic diversity to survive the coming climatic shit-storms, then we should let them explore it and just facilitate the process. Free the trees, dammit!

Note: See (1) J. Russell Smith’s Tree Crops, (2) Mark Shepard’s Restoration Agriculture, (3) Samuel Thayer’s Nature’s Garden, and (4) the wonderful Oikos Tree Crops website (

http://www.oikostreecrops.com/) for more details on breeding, wild cultivars, and genetic diversity.

4. MODEST FARM-SIZED SCALE:

Manage each orchard on a modest farm-sized scale.

Why? To address drought, deluge, pests, nutrients, theft, labor, and storage. Explanation: The industrial orchard ‘economies of scale’ were intended to maximize abstract monetary profits by reducing infrastructure and labor costs and increasing volume -- while also scandalously ignoring a host of very real and very substantial energetic, environmental, and social costs. But in the post-industrial era, we will no longer care about such narrowly-defined ‘profits’, and we will no longer be able to ignore these long-ignored costs. In short, we will find that a return to a much more modest orchard scale will be as unavoidable as it is beneficial and enjoyable.

How does a post-industrial family water 1000 acres of newly-planted seedlings by hand during a punishing early-summer drought? Answer: They can’t. But they can – with much effort – water, say, 15 acres of new seedlings. The same small-is-easier principle applies to orchard maintenance, harvest, processing, and storage: In the absence of fossil energy, we will need to run these orchards on mostly human labor at traditional, farm-sized, human scales. One family (or small community) can accomplish an awful lot with just their own bodies and a little supplemental draft/solar/wind/hydro power – but the hitches are that (1) there is a limit to what that one family (or community) can accomplish in a year, and (2) the work must be spread out over a sufficiently long window so as not to overload the people and their energy sources. Quickly ramping up production by seasonal importation of labor and labor-saving machinery will no longer be an option. Maintenance of people-sized orchard scales will be our only choice.

Furthermore, an overriding concern for these post-industrial, ecosystem-partnered orchards will be the maintenance of ecosystem health and sufficiently closed nutrient cycles. Such place-based concerns need to be addressed quite differently on each farm, requiring ever-present, knowledgeable eyes – what Wes Jackson calls a high “eyes to acres” ratio. For example, if there’s a gully starting to open up at some stream-head, someone needs to (1) be there to notice it, (2) care that it’s happening, and (3) have the time and knowledge to fix it.

We can no longer afford to manage any given 50 acres all the same. (But could we ever? We really just pretended to be able to afford it!) Only small family & community managed farms will allow such careful caretaking of the land – as well as the resulting higher probabilities that the land will take care of us.

5. CUSTOMIZED ACCOMPANIMENTS:

5. CUSTOMIZED ACCOMPANIMENTS:

Include other biological elements to complement the trees.

Why? To both generate a living yield while the orchard is maturing and increase total baseline yield of the mature orchard. Explanation: The orchard can and should be so much more than just the trees. There are two main reasons for this – one having to do with the early stages of orchard development and one having to do with the mature orchard.

Firstly, in advocating for a perennial-based agriculture we’re asking farmers to plant tree crops that don’t start generating any measurable yield for 10 to 20 years! What are they supposed to do in the meantime? Watch trees grow? …Well, yes, actually -- but there are a bunch of other transitional additions to a developing orchard that can generate food and income while the trees are growing.

A few of these transitional options include:

- Growing hay and/or grazing sheep, cows, and laying hens amongst the growing trees,

- Alley-cropping strips of annual crops in the rows between the trees,

- Establishing relatively quick-yielding fruit and nut bushes (hazelnut, gooseberry, etc.) in and between the tree rows, and

- Including timber trees to be thinned out or coppiced as the fruit and nut trees mature. See Mark Shepard’s wonderful Restoration Agriculture for a demonstration of farm-scale applications of these techniques.

The second reason to include these other elements in the orchard is to take advantage of the phenomenon of ‘overyielding’ – where additional elements in the mature orchard decrease the yield of each individual crop, but generate a higher overall yield. For example, planting rows of hazelnut and gooseberry bushes in the tree rows will result in slightly lower yields of tree fruit and nuts, but a higher yield of all fruit and nuts from the orchard. This boost in yield results from both a more efficient use of the soil profile, and a more efficient gathering of sunlight energy in the multi-layered physical structure.

And while we need more than just trees in these orchards, each farm will be different. Because what that ‘more’ is depends on both the people and the land: What else do you want on the farm? What will work on the land? What does the land need? ...So go ahead, ask.

6. START NOW!!!:

We need to start planting these orchards right away – and then keep planting!

Why? Economic collapse and climate destabilization are accelerating. Explanation: We need to get our hands on as much tree diversity as possible, as soon as possible – including both a wide variety of species and rich diversity within species. Once the economy unravels sufficiently, fossil fuels and the easy transport they provide will become scarce for the average American. Access to mail-ordered trees from other states will become problematic. Even contact between different growers in the same county will likely become difficult.

So we need to get whatever tree-crop genetics we can, while we can – because that’s what we’ll have to work with as the climate unravels. And as the climate unravels, only a robust diversity will be able to provide us with the crucial steady baseline yield we’ll need to survive.

Now, I realize that my suggestions here are not the ones most experienced orchardists are making right now. But most experienced orchardists don’t have an eye on the rapidly crumbling industrial economy and all the luxuries we are soon to lose. And most experienced orchardists, while certainly noticing something amiss with the climate already, are not tuned into the alarming extent of climatic destabilization we are now expected to see. And that’s why most experienced orchardists are still married to the doomed orcharding paradigms of maximized yield, monoculture, and/or industrial biocides.

But I don’t imagine it will stay that way. Those ways simply won’t work much longer. There are big dark things looming on the biophysical horizon and I suspect it won’t be too long before my suggestions become actual requirements. And then, a true partnership with the land to grow our food will no longer be an ‘inefficient and idealistic’ choice – it’ll be a damn necessity.

VI. ONE EXAMPLE OF A RESILIENT ORCHARD FOR CENTRAL NEW JERSEY

“I have altogether something like a hundred varieties of walnuts, hickories, pecans, persimmons, pawpaws, and honey locust on test on my rocky hillside, and I find that I am having an amount of fun that is…perfectly unreasonable” – J. Russell Smith (in Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, 1950)

OK, so we’ve gone over the types of climatic and economic limitations our post-industrial orchards will face, and we’ve discussed some design guidelines that may help to address these limitations. But what exactly would such an orchard look like?

A quick search of the permaculture literature can give you a bunch of mature, mixed orchard or forest-farm examples. Here are a few of them:

Unfortunately, the design guidelines I outlined above didn’t pop into my head, fully-formed, fifteen years ago when I started planting trees. Thus I don’t have a nice fifteen year old example, designed by the above suggestions, to show you. My plantings are scattered all over the place – wherever I have found room.

But in the spirit of the general guidelines above, I’ll just sketch out a sample acre of the kind of resilient, mixed species orchard that I’ll be planting in central NJ – not as a template for what you should do on your farm, but to just flesh out some of the stuff I’ve been talking about. So here it is:

- Nuts I know can work on my farm without fossil fuels: (1) Chinese chestnut, (2) black walnut, (3) shagbark hickory, (4) northern-hardy pecan, (5) American hazelnut, (6) red oak, and (7) honey locust.

- Fruits I know can work on my farm without fossil fuels: (1) apple, (2) pear, (3) peach, (4) sour cherry, (5) persimmon, (6) pawpaw, (7) apricot, (8) asian pear, and (9) mulberry.

- Information on these tree-crop species: If you’re interested or skeptical about these trees as food crops, see (1) J. Russell Smith’s Tree Crops, (2) Mark Shepard’s Restoration Agriculture, (3) Samuel Thayer’s Nature’s Garden, and (4) the wonderful Oikos Tree Crops website (http://www.oikostreecrops.com/) for information on these and a bunch of other possible tree crop species.

- …And I’m still looking for more trees: I’m also in the process of testing other possibilities: hybrid hazelnuts, asian persimmon, Japanese walnut, hybrid plum, Persian walnut, and others – all of which have a chance to making it to the ‘big leagues’ (lists above) if they work out. In addition, blight-resistant American chestnuts from the ACF breeding program are set to be released to the public in the next few years, so I’ll likely be adding them too, if all goes as planned.

- Tree spacing: For simplicity, I’ll use 33’x33’ spacing here – which would require future thinning for some larger species (e.g., oak, pecan), and multiple trees together for some smaller species (e.g., pawpaw, hazelnut). But 33’ is a good one-size-fits all spacing to use here – mostly since it fits nicely in the 1-acre grid below. There are, of course, many spacing and inter-planting schemes possible (e.g., see Shepard’s Restoration Agriculture) – each orchard can literally become a work of art.

Figure 3: One possible multi-species tree-crop planting in Central NJ.

Figure 3: One possible multi-species tree-crop planting in Central NJ.

Each square is 33’x33’. The whole grid is one acre (200’x200’).

Key characteristics: deep perennial roots, family/genus diversity, and diversity within each species.

Goal: Super-resilient, low-input baseline yield of food, rather than high-input, maximized yield. Spacing and species can vary widely from farm to farm (or even within a farm), but the general principles will likely become more and more crucial for agriculture across the US as the economy collapses and the climate destabilizes.

VII. GOOD WORK IN THE AGE OF CONSEQUENCE

VII. GOOD WORK IN THE AGE OF CONSEQUENCE

“All of us have been fighting a battle that on average we are losing, and I doubt that there is any use in reviewing the statistical proofs. The point – the only interesting point – is that we have not quit. …We have not quit because we are not hopeless. …I am not looking for reasons to give up. I am looking for reasons to keep on.” -- Wendell Berry (in Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture)

Now bite your lower lip and listen to this: As a 10,000-year-old agricultural civilization, we have behaved dreadfully, even homicidally. As the fierce, 200-year-old industrial variant of that civilization, we have behaved abominably, even suicidally. The damage has been staggering, the losses incalculable. And as the land has suffered, so have we -- despite the delusional bromides we sing to ourselves. But in the coming decades and centuries, we will reap the full consequences of our past behavior. And these consequences will undoubtedly be severe. They will quite possibly be terminal.

The fact that the above paragraph is unpleasant doesn’t mean we can make it go away by collective denial.

But the fact that the above paragraph is true doesn’t mean I am absolved from trying my damndest to make things right.

So I will try to make things right. Which is why I do the work I do with trees, and which is why I speak and write about how we might go about fashioning a resilient agriculture that doesn’t destroy the land.

It is, I feel, good work.

And by doing this good work, it is my hope that you too will do good work; that you too will work to make things right.

And that perhaps we actually will make things right – perhaps truly right, but perhaps only a little bit right, and perhaps only for a short time.

But in any case, it will be the best that we can do.

And it just feels like the right thing to do.

So I will do it. So we will do it. So we must do it. Now.

…Good luck.

Now get outside and talk to the land.

.