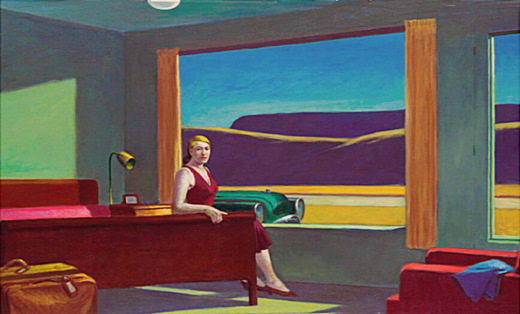

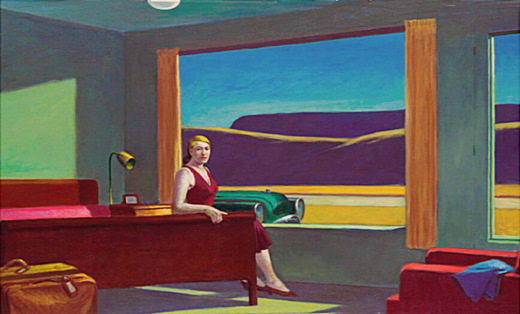

SUBHEAD: Edward Hopper's painting "Western Motel" has been built and occupied in a museum.

By David Pescovitz on 22 November 2019 for Boing Boing -

(https://boingboing.net/2019/11/22/sleeping-inside-one-of-edward.html)

Image above: Painting "Western Motel" by Edward Hopper 1957. From original article. Click to enlarge.

As part of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts' "Edward Hopper and the American Hotel" exhibition, the curators have created a brilliant installation and visitor experience that's seemingly made for Instagram.

They built a physical version of Hopper's above painting "Western Hotel" (1957) and offered overnight stays inside the artwork. The overnight packages sold out very quickly. The New York Times' Margot Boyer-Dry was one of the first guests:

Every detail here was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1957 painting “Western Motel,” which has been brought to vibrant, three-dimensional life. The only thing missing is the mysterious woman whose burgundy dress matches the bedspread. But that’s where the museum guest comes in.

I was the second person to stay in the museum’s Hopper hotel room, essentially becoming its subject for a night. (Before it sold out through February, the room cost anywhere from $150 a night to $500 for a package, including dinner, mini golf and a tour with the curator.)

My time there was short — a standard stay runs from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m. — and awkward. I had traveled all day to reach Richmond, and these pristinely basic quarters were the main event. Ultimately, it reminded me of every other hotel room I’ve ever stayed in...

Ellen Chapman, a Richmond resident who stayed the night before I did, was more focused on the novelty of an art overnight. “I’ve always had that childhood fantasy of spending the night in a museum,” she said. “The remarkable part for me was waking up, drinking my coffee and looking at this amazing exhibit right next to me.”

Every detail of Edward Hopper’s “Western Motel” has been brought to life at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where you can spend the night https://nyti.ms/34a1vl1

What's Better than Seeing a Hopper Painting?

(https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/edward-hopper-virginia-museum.html)

By Margot Boyer-Dry on 21 November 2019 for theNew York Times

Image above: Museum visitor viewing "Western Motel" installation that is rented out as a hotel room within the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. From original article. Click to enlarge.

Behind a pane of glass at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, a wooden bed frame anchors a sparsely decorated motel room. Vintage suitcases have been arranged at the foot of the bed, and light streams in diagonally through a window, just beyond which a green Buick is visible, parked in the foreground of a mesa landscape.

It looks like the setting of a painting, and it is. Every detail here was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1957 painting “Western Motel,” which has been brought to vibrant, three-dimensional life. The only thing missing is the mysterious woman whose burgundy dress matches the bedspread. But that’s where the museum guest comes in.

I was the second person to stay in the museum’s Hopper hotel room, essentially becoming its subject for a night. (Before it sold out through February, the room cost anywhere from $150 a night to $500 for a package, including dinner, mini golf and a tour with the curator.)

My time there was short — a standard stay runs from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m. — and awkward. I had traveled all day to reach Richmond, and these pristinely basic quarters were the main event. Ultimately, it reminded me of every other hotel room I’ve ever stayed in.

The “Hopper Hotel Experience” is the flashy centerpiece of “Edward Hopper and the American Hotel,” an exhibition featuring about 60 of the artist’s hospitality-themed works, including paintings, sketches and early-career cover illustrations for the trade magazine, Hotel Management.

Also on view are 35 works by other American artists exploring travel in America across time and medium, from Robert Salmon’s 1830 painting “Dismal Swamp Canal” to a 2009 photograph by Susan Worsham titled “Marine, Hotel Near Airport, Richmond, VA.”

Leo G. Mazow, the show’s curator, said he intends the Hopper room to do more than just generate buzz. “So many people say, ‘Well, Hopper’s about alienation.’” But for Mr. Mazow, Hopper’s themes of “transience and transportation yield a particular type of detachment,” which the hotel experience explores.

Hopper’s painting career coincided with the period when automobile production and expanding highway infrastructure made travel possible for a broader range of Americans.

A lifelong New Yorker, Hopper and his wife, Jo, took several extended road trips, during which he painted common elements of American life: hotels, motels and guesthouses; lighthouses; restaurants; city streets and interiors. His quietly dramatic depictions of those spaces and the people in them came to define an American aesthetic.

Image above: Ellen Chapman, a resident of Richmond, Va., inside the Hopper room at the museum. She said her stay fulfilled a childhood fantasy. From original article. Click to enlarge.

By David Pescovitz on 22 November 2019 for Boing Boing -

(https://boingboing.net/2019/11/22/sleeping-inside-one-of-edward.html)

Image above: Painting "Western Motel" by Edward Hopper 1957. From original article. Click to enlarge.

As part of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts' "Edward Hopper and the American Hotel" exhibition, the curators have created a brilliant installation and visitor experience that's seemingly made for Instagram.

They built a physical version of Hopper's above painting "Western Hotel" (1957) and offered overnight stays inside the artwork. The overnight packages sold out very quickly. The New York Times' Margot Boyer-Dry was one of the first guests:

Every detail here was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1957 painting “Western Motel,” which has been brought to vibrant, three-dimensional life. The only thing missing is the mysterious woman whose burgundy dress matches the bedspread. But that’s where the museum guest comes in.

I was the second person to stay in the museum’s Hopper hotel room, essentially becoming its subject for a night. (Before it sold out through February, the room cost anywhere from $150 a night to $500 for a package, including dinner, mini golf and a tour with the curator.)

My time there was short — a standard stay runs from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m. — and awkward. I had traveled all day to reach Richmond, and these pristinely basic quarters were the main event. Ultimately, it reminded me of every other hotel room I’ve ever stayed in...

Ellen Chapman, a Richmond resident who stayed the night before I did, was more focused on the novelty of an art overnight. “I’ve always had that childhood fantasy of spending the night in a museum,” she said. “The remarkable part for me was waking up, drinking my coffee and looking at this amazing exhibit right next to me.”

Every detail of Edward Hopper’s “Western Motel” has been brought to life at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where you can spend the night https://nyti.ms/34a1vl1

What's Better than Seeing a Hopper Painting?

(https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/21/arts/design/edward-hopper-virginia-museum.html)

By Margot Boyer-Dry on 21 November 2019 for theNew York Times

Image above: Museum visitor viewing "Western Motel" installation that is rented out as a hotel room within the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. From original article. Click to enlarge.

Behind a pane of glass at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, a wooden bed frame anchors a sparsely decorated motel room. Vintage suitcases have been arranged at the foot of the bed, and light streams in diagonally through a window, just beyond which a green Buick is visible, parked in the foreground of a mesa landscape.

It looks like the setting of a painting, and it is. Every detail here was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1957 painting “Western Motel,” which has been brought to vibrant, three-dimensional life. The only thing missing is the mysterious woman whose burgundy dress matches the bedspread. But that’s where the museum guest comes in.

I was the second person to stay in the museum’s Hopper hotel room, essentially becoming its subject for a night. (Before it sold out through February, the room cost anywhere from $150 a night to $500 for a package, including dinner, mini golf and a tour with the curator.)

My time there was short — a standard stay runs from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m. — and awkward. I had traveled all day to reach Richmond, and these pristinely basic quarters were the main event. Ultimately, it reminded me of every other hotel room I’ve ever stayed in.

The “Hopper Hotel Experience” is the flashy centerpiece of “Edward Hopper and the American Hotel,” an exhibition featuring about 60 of the artist’s hospitality-themed works, including paintings, sketches and early-career cover illustrations for the trade magazine, Hotel Management.

Also on view are 35 works by other American artists exploring travel in America across time and medium, from Robert Salmon’s 1830 painting “Dismal Swamp Canal” to a 2009 photograph by Susan Worsham titled “Marine, Hotel Near Airport, Richmond, VA.”

Leo G. Mazow, the show’s curator, said he intends the Hopper room to do more than just generate buzz. “So many people say, ‘Well, Hopper’s about alienation.’” But for Mr. Mazow, Hopper’s themes of “transience and transportation yield a particular type of detachment,” which the hotel experience explores.

Hopper’s painting career coincided with the period when automobile production and expanding highway infrastructure made travel possible for a broader range of Americans.

A lifelong New Yorker, Hopper and his wife, Jo, took several extended road trips, during which he painted common elements of American life: hotels, motels and guesthouses; lighthouses; restaurants; city streets and interiors. His quietly dramatic depictions of those spaces and the people in them came to define an American aesthetic.

Image above: Ellen Chapman, a resident of Richmond, Va., inside the Hopper room at the museum. She said her stay fulfilled a childhood fantasy. From original article. Click to enlarge.