SUBHEAD: This story is no longer just about the bees, but also butterflies, and even people.

By Andy Russell on 26 August 2014 for Autonomy Acres -

(http://autonomyacres.wordpress.com/2014/08/26/an-unplanned-break-writers-block-and-the-art-of-extinction/)

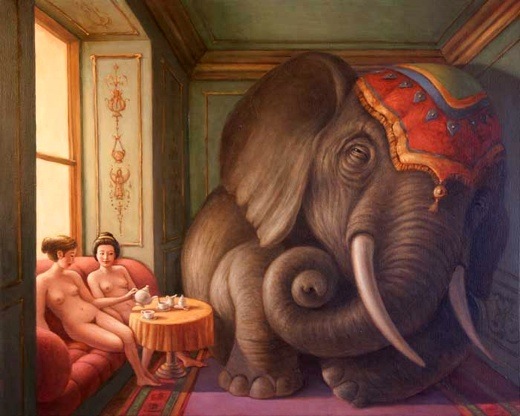

Image above: GMOs threaten bees and butterflies (Essentially food and life as you know it). From (http://www.fabulousfoodlife.com/gmos-threaten-bees-butterflies-essentially-food-life-as-you-know-it/).

While the title of this essay may be tinted with a bit of doom and gloom, it is not as ominous as it sounds, and it is a fairly accurate description of the events and stories that follow. For anyone who has followed this blog over the last five years may have noticed, I have gone through periods of consistent, productive writing, balanced out with dry periods of nothing but writers’ block growing up through the cracks of my mindscape.

While these droughts have been few for the most part, this last one has been pretty epic in scale! The last time I sat down to write was back in February of this year when I continued with an ongoing series of essays about DIY homebrewing.

Since this last winter (the one filled with all of the Polar Vortexes) many things have happened here at the Dead End Alley Farm, and much of it would have made great copy for essays and DIY how – to’s here on the blog. I am not going to touch on everything, but I guess it is time for us to catch up on current events and happenings around the homestead and the world at large.

As I sit here in the afternoon shade with a cold beer in the outside office (a picnic table and some benches, and a hacked together arbor covered in wild grapes and honeysuckle) I am listening to one of the hens cluck away in pride or fear or some other emotion that only a chicken can know. I can see bumble bees feeding on white clover and catnip, an overcast sky, and my old dog Harvey lying in the grass watching the world go by.

There are parts of our yard that are overgrown with weeds that should have been ripped from the ground long ago, and some of our apple trees (especially the big old one in back) are beginning to shed apples like drops of rain. There is garlic hanging from the roof joists of my back deck and the tomato plants are overloaded with luscious fruit this year.

I have three hives of bees this season. My pride and joy are the Carniolans that overwintered and have proven to be exceptional bees. They are 3 deep with 2 honey supers (which translates to a very healthy colony that is making a lot of honey), a naturally mated queen (who may be the same one from last year, not real sure if they have swarmed or not this season) leads this tribe, and they are poised to enter this upcoming winter appearing very strong and healthy with adequate food supplies.

This spring I also purchased 2 packages of hybrid Buckfast bees that came up from Georgia. Sadly one perished within the first week (dead queen), but the other one has shown to be a vigorous (if not a bit pissy) hive of bees.

At last check they were finishing up drawing out comb and making honey in 3 deep boxes which should be enough stores for winter. And throughout the early part of the year these Buckfast bees provided frames of brood and eggs to help strengthen my Carniolans, and have also helped out to create a third colony.

At the end of June I came across a local company, 4 Seasons Apiaries, that specializes in locally bred queens and nucs. This is a huge deal for us in Minnesota, not only for the fact that it is hard to find northern bred queens anywhere, but because it was only 20 minutes from my house as the car drives. I ended up purchasing a really dark queen for $28 and put together a split that was made up of two frames each of the Buckfasts and the Carniolans.

The jury is still out on how this hive is doing though. The queen is laying eggs, there is brood (both capped and otherwise), and they are actually making quite a bit of honey, but their overall numbers seem low to me. They will most likely be subsidized with honey from the Carniolans this winter in hopes that they will have enough food to survive the cold, dark days of the upper midwest winter.

While I cross my fingers in hopes that all 3 of my colonies will pull through and survive this upcoming winter, observation and common sense tell me that the likelihood of all 3 surviving is slim at best. Current numbers from this last winters survival rate was anywhere from about 30-50%. These are horseshit numbers when compared to 20-30 years ago when a beekeeper could expect close to 90% survival rate in their apiaries.

So the same story continues for the bees. While the numbers of reported cases of colony collapse disorder have evened out (and possibly plateaued), bee losses continue throughout many parts of the world, but seem especially high here in America.

Why this is such a surprise to people baffles me. Our modern – mono crop – anthropocentric ways of inhabiting this planet are not compatible with a diverse, living, natural world. This story is no longer just about the bees, but also of the monarch butterfly, the oceans, the remaining old growth forests of the world, and even people.

Habitat destruction, climate change, slavery, edible-food-like-products engineered to grow with poison, industrial pollution, and profit – from – disease are all symptoms of the overarching cancer that is this modern day capitalist society. It has grown up around us over the last 300 years, the whole time was spent in a petrochemical party binge, and now that we are drying out we are starting to feel the hangover!

It is as simple as this – when the bees lose, we lose, and that is the road we are going down. The world that we live in, regardless of your flavor of religion, or politics, or indifference is still ruled by cold hard facts established through observation and the scientific method. The world is changing, mainly its’ climate, but also the make-up of its varied populations.

Every day the Earth loses another creature, another plant. The last of manifest destiny is completing itself as the few remaining “wild” people are driven from their forest homes, and the blood of ethnic genocide still waters the tree of “Liberty” for those of us in the privileged world .

This spring my family experienced climate change first hand. For some naive reason I thought we were insulated from climate change here in Minnesota, but was I wrong!

Starting towards the end of May and going through towards the end of June, we received upwards of 15 inches of rain for the month, with a lot of this rain coming in bursts of multiple inches in short periods of time. At some point a sewer line about a block and a half away from my home could no longer keep up with the amount of stormwater entering the system and literally collapsed in on itself.

This blockage led to my whole neighborhoods’ sanitary sewers backing up and we had upwards of 14 inches of sewage water in our basements!

Lets just say it was a real shitty and smelly problem to clean up. To add to the mess, the city that I live in is not claiming any real responsibility for the sewer collapsing. They are saying that the amount of rain that we received is to blame (because no one could have predicted that we would ever get that much rain in such a small space of time), and it is not their problem that the sewer wasn’t designed to handle that much water.

This situation is a good illustration of the intersecting problems of failing infrastructure and its ability to deal with the symptoms of climate change.

Not only is it bad enough that our infrastructure is falling apart and failing throughout the country, climate change will only hasten the collapse of these systems that we take for granted.

As there is less and less money to spend on domestic infrastructure projects and basic preventative maintenance, and the ever increasing threats of unstable weather conditions loom closer on all of our horizons, our roads and sewers and all the other systems that make modern lifestyles possible will be challenged and frequently overcome by a force far greater than themselves.

What is the quick take away from this conversation? That as we face the future of a world that struggles to adapt to a changing climate with far fewer cheap resources on hand to work with, we can no longer rely on the long term support of our governments to solve these problems or to even help clean up the messes that ensue.

Just think back to hurricanes Katrina or Sandy (or any number of other climate disasters that happen regularly around the world) and you have all the evidence that you need to show government ineptitude when a climate-crisis strikes.

Most of the collapse will be slow and unnoticeable except for those places directly affected by whatever natural disaster decides to strike next. But with each changing season, and every new climate change induced disaster, bit by bit the comfort and convenience that we are used to will begin to erode away.

As long as we keep spending our resources, whether that be gold or oil, in a way that denies climate change and resource depletion, we will find ourselves in a world that is an empty shell of the one we now know.

If I were a religious man I may start praying extra hard right now, but thankfully I let science rather than superstition guide my life. Critical observation and the ability to make rational decisions based on the facts is important.

Not just for a nation or a civilization, but also on the personal and family level. I think if there is anything I have learned, is that when we can look at problems on multiple levels, do the research that is needed to educate ourselves on these problems, and then make decisions based on these observations to correct the problem, we can do a lot just in our own lives to change the course of events, and add a bit of resiliency and human spirit back into our everyday lives.

As briefly mentioned here in other posts, a year and a half ago I quit a long time job of mine in favor of one that affords me far more free time.

The trade off has been huge, and sometimes quite challenging. This has been my second summer off, and my first full season as a partially self employed, full time stay at home dad. It has probably been the most eye opening, and sometimes hardest role I have ever had to play.

Being use to the role as the main breadwinner in my family for so long and then giving up that economic control is not easy, but a lesson that I urge you to all try at some point in your life. After these last few months of being at home with the kids, I have a far greater appreciation and respect for the work that my wife (as well as all you other moms out there!) has done over the last 8 years.

Child rearing is the hardest thing I have ever participated in, but I am glad that I have had the chance to dive in full time.

For me the hardest part has been balancing time between time actively spent with the kids, chores, and coordinating our CSA. The CSA we run is small. 2 full shares, and 2, ½ shares, but it gave me a nice chunk of cash in the spring and early summer for things like groceries (I can’t grow cheese cake!) and gas money.

That cash is gone now, so my new endeavor is working on a business plan that expands out from the CSA in other directions to increase my summer cash flow for a few more months.

Eventually I hope to start making a bit of money by raising bees to sell, starting a small plant nursery, and I am also exploring some options for teaching classes. Using outlets like the public library system, community education, and space at my local co-op,

I am hoping to put together a selection of classes that will include introductions to beekeeping and Permaculture, and also a tree grafting workshop each spring. I am in the early phases of research and planning, but I hope to teach my first official tree grafting class this upcoming spring (contact me if you are interested in hosting a class).

I guess when I really sit down and think about it, my ultimate long term goal is to not have to ever work a full time job again, unless it is for myself. I am not scared of hard work, but it comes back to the fact that I am no longer alright selling my time to some asshole when I am fully capable of doing something(s) I am passionate about and generate an income for myself at the same time.

Is this selfish? Maybe, but I am okay with that as well. I have begun to realize more than ever most people are just clueless drones. Who after years of taking orders, and numbing themselves with TV, processed food, and fanatical beliefs in fairy tales can no longer truly take care of themselves or make desicions that impact their destiny.

As it stands, with humans being prisoners to their own creations and all, I do not have a lot of hope for humanity right now.

If you follow David Holmgren’s work Future Scenarios, we are most likely entering into the Brown Tech future. A world where we will continue draining the Earth of its fossil fuels, destroying the last of the wild lands, converting more and more of that land to desertscapes of monocrops, and the further erosion of our shared cultural heritage, modern Homo Sapiens have perfected the art of extinction.

It is a bleak future. One that leaves less and less room for those of us who seek freedom and justice. It is a world that has been reduced to cultural poverty by traditions and tragedies alike.

It is a world where all life on Earth has been reduced to interchangeable and disposable parts in the pursuit of Progress. It is a world filled with death and injustice, but it is also falling apart.

Whether humans can survive this collapse of our own making is yet to be determined. It will be hard, but even the strongest rock is defeated by water and wind in the end. It is in these cracks and fissures that we can seek our refuge. The spots forgotten about and overlooked. The areas where literal and figurative weeds grow. The edges. The TAZs where humanity still flourish.

Go on hikes. Hunt mushrooms. Raise bees. Raise Kids. Bake bread. Love. Hate. Grow some carrots. Chop some wood. Pull some weeds. Laugh. Hug a puppy. Cry. Resist! Grow. Take a nap. Rise up! Read a book. Lend a hand. Take notes. Have fun. Fish. Visit a friend. Hug your mom. Plant trees. Be human….

.

By Andy Russell on 26 August 2014 for Autonomy Acres -

(http://autonomyacres.wordpress.com/2014/08/26/an-unplanned-break-writers-block-and-the-art-of-extinction/)

Image above: GMOs threaten bees and butterflies (Essentially food and life as you know it). From (http://www.fabulousfoodlife.com/gmos-threaten-bees-butterflies-essentially-food-life-as-you-know-it/).

While the title of this essay may be tinted with a bit of doom and gloom, it is not as ominous as it sounds, and it is a fairly accurate description of the events and stories that follow. For anyone who has followed this blog over the last five years may have noticed, I have gone through periods of consistent, productive writing, balanced out with dry periods of nothing but writers’ block growing up through the cracks of my mindscape.

While these droughts have been few for the most part, this last one has been pretty epic in scale! The last time I sat down to write was back in February of this year when I continued with an ongoing series of essays about DIY homebrewing.

Since this last winter (the one filled with all of the Polar Vortexes) many things have happened here at the Dead End Alley Farm, and much of it would have made great copy for essays and DIY how – to’s here on the blog. I am not going to touch on everything, but I guess it is time for us to catch up on current events and happenings around the homestead and the world at large.

As I sit here in the afternoon shade with a cold beer in the outside office (a picnic table and some benches, and a hacked together arbor covered in wild grapes and honeysuckle) I am listening to one of the hens cluck away in pride or fear or some other emotion that only a chicken can know. I can see bumble bees feeding on white clover and catnip, an overcast sky, and my old dog Harvey lying in the grass watching the world go by.

There are parts of our yard that are overgrown with weeds that should have been ripped from the ground long ago, and some of our apple trees (especially the big old one in back) are beginning to shed apples like drops of rain. There is garlic hanging from the roof joists of my back deck and the tomato plants are overloaded with luscious fruit this year.

I have three hives of bees this season. My pride and joy are the Carniolans that overwintered and have proven to be exceptional bees. They are 3 deep with 2 honey supers (which translates to a very healthy colony that is making a lot of honey), a naturally mated queen (who may be the same one from last year, not real sure if they have swarmed or not this season) leads this tribe, and they are poised to enter this upcoming winter appearing very strong and healthy with adequate food supplies.

At last check they were finishing up drawing out comb and making honey in 3 deep boxes which should be enough stores for winter. And throughout the early part of the year these Buckfast bees provided frames of brood and eggs to help strengthen my Carniolans, and have also helped out to create a third colony.

At the end of June I came across a local company, 4 Seasons Apiaries, that specializes in locally bred queens and nucs. This is a huge deal for us in Minnesota, not only for the fact that it is hard to find northern bred queens anywhere, but because it was only 20 minutes from my house as the car drives. I ended up purchasing a really dark queen for $28 and put together a split that was made up of two frames each of the Buckfasts and the Carniolans.

The jury is still out on how this hive is doing though. The queen is laying eggs, there is brood (both capped and otherwise), and they are actually making quite a bit of honey, but their overall numbers seem low to me. They will most likely be subsidized with honey from the Carniolans this winter in hopes that they will have enough food to survive the cold, dark days of the upper midwest winter.

While I cross my fingers in hopes that all 3 of my colonies will pull through and survive this upcoming winter, observation and common sense tell me that the likelihood of all 3 surviving is slim at best. Current numbers from this last winters survival rate was anywhere from about 30-50%. These are horseshit numbers when compared to 20-30 years ago when a beekeeper could expect close to 90% survival rate in their apiaries.

Why this is such a surprise to people baffles me. Our modern – mono crop – anthropocentric ways of inhabiting this planet are not compatible with a diverse, living, natural world. This story is no longer just about the bees, but also of the monarch butterfly, the oceans, the remaining old growth forests of the world, and even people.

Habitat destruction, climate change, slavery, edible-food-like-products engineered to grow with poison, industrial pollution, and profit – from – disease are all symptoms of the overarching cancer that is this modern day capitalist society. It has grown up around us over the last 300 years, the whole time was spent in a petrochemical party binge, and now that we are drying out we are starting to feel the hangover!

It is as simple as this – when the bees lose, we lose, and that is the road we are going down. The world that we live in, regardless of your flavor of religion, or politics, or indifference is still ruled by cold hard facts established through observation and the scientific method. The world is changing, mainly its’ climate, but also the make-up of its varied populations.

Every day the Earth loses another creature, another plant. The last of manifest destiny is completing itself as the few remaining “wild” people are driven from their forest homes, and the blood of ethnic genocide still waters the tree of “Liberty” for those of us in the privileged world .

This spring my family experienced climate change first hand. For some naive reason I thought we were insulated from climate change here in Minnesota, but was I wrong!

Starting towards the end of May and going through towards the end of June, we received upwards of 15 inches of rain for the month, with a lot of this rain coming in bursts of multiple inches in short periods of time. At some point a sewer line about a block and a half away from my home could no longer keep up with the amount of stormwater entering the system and literally collapsed in on itself.

This blockage led to my whole neighborhoods’ sanitary sewers backing up and we had upwards of 14 inches of sewage water in our basements!

Lets just say it was a real shitty and smelly problem to clean up. To add to the mess, the city that I live in is not claiming any real responsibility for the sewer collapsing. They are saying that the amount of rain that we received is to blame (because no one could have predicted that we would ever get that much rain in such a small space of time), and it is not their problem that the sewer wasn’t designed to handle that much water.

This situation is a good illustration of the intersecting problems of failing infrastructure and its ability to deal with the symptoms of climate change.

Not only is it bad enough that our infrastructure is falling apart and failing throughout the country, climate change will only hasten the collapse of these systems that we take for granted.

As there is less and less money to spend on domestic infrastructure projects and basic preventative maintenance, and the ever increasing threats of unstable weather conditions loom closer on all of our horizons, our roads and sewers and all the other systems that make modern lifestyles possible will be challenged and frequently overcome by a force far greater than themselves.

What is the quick take away from this conversation? That as we face the future of a world that struggles to adapt to a changing climate with far fewer cheap resources on hand to work with, we can no longer rely on the long term support of our governments to solve these problems or to even help clean up the messes that ensue.

Just think back to hurricanes Katrina or Sandy (or any number of other climate disasters that happen regularly around the world) and you have all the evidence that you need to show government ineptitude when a climate-crisis strikes.

Most of the collapse will be slow and unnoticeable except for those places directly affected by whatever natural disaster decides to strike next. But with each changing season, and every new climate change induced disaster, bit by bit the comfort and convenience that we are used to will begin to erode away.

As long as we keep spending our resources, whether that be gold or oil, in a way that denies climate change and resource depletion, we will find ourselves in a world that is an empty shell of the one we now know.

If I were a religious man I may start praying extra hard right now, but thankfully I let science rather than superstition guide my life. Critical observation and the ability to make rational decisions based on the facts is important.

Not just for a nation or a civilization, but also on the personal and family level. I think if there is anything I have learned, is that when we can look at problems on multiple levels, do the research that is needed to educate ourselves on these problems, and then make decisions based on these observations to correct the problem, we can do a lot just in our own lives to change the course of events, and add a bit of resiliency and human spirit back into our everyday lives.

The trade off has been huge, and sometimes quite challenging. This has been my second summer off, and my first full season as a partially self employed, full time stay at home dad. It has probably been the most eye opening, and sometimes hardest role I have ever had to play.

Being use to the role as the main breadwinner in my family for so long and then giving up that economic control is not easy, but a lesson that I urge you to all try at some point in your life. After these last few months of being at home with the kids, I have a far greater appreciation and respect for the work that my wife (as well as all you other moms out there!) has done over the last 8 years.

Child rearing is the hardest thing I have ever participated in, but I am glad that I have had the chance to dive in full time.

For me the hardest part has been balancing time between time actively spent with the kids, chores, and coordinating our CSA. The CSA we run is small. 2 full shares, and 2, ½ shares, but it gave me a nice chunk of cash in the spring and early summer for things like groceries (I can’t grow cheese cake!) and gas money.

That cash is gone now, so my new endeavor is working on a business plan that expands out from the CSA in other directions to increase my summer cash flow for a few more months.

Eventually I hope to start making a bit of money by raising bees to sell, starting a small plant nursery, and I am also exploring some options for teaching classes. Using outlets like the public library system, community education, and space at my local co-op,

I am hoping to put together a selection of classes that will include introductions to beekeeping and Permaculture, and also a tree grafting workshop each spring. I am in the early phases of research and planning, but I hope to teach my first official tree grafting class this upcoming spring (contact me if you are interested in hosting a class).

I guess when I really sit down and think about it, my ultimate long term goal is to not have to ever work a full time job again, unless it is for myself. I am not scared of hard work, but it comes back to the fact that I am no longer alright selling my time to some asshole when I am fully capable of doing something(s) I am passionate about and generate an income for myself at the same time.

Is this selfish? Maybe, but I am okay with that as well. I have begun to realize more than ever most people are just clueless drones. Who after years of taking orders, and numbing themselves with TV, processed food, and fanatical beliefs in fairy tales can no longer truly take care of themselves or make desicions that impact their destiny.

As it stands, with humans being prisoners to their own creations and all, I do not have a lot of hope for humanity right now.

If you follow David Holmgren’s work Future Scenarios, we are most likely entering into the Brown Tech future. A world where we will continue draining the Earth of its fossil fuels, destroying the last of the wild lands, converting more and more of that land to desertscapes of monocrops, and the further erosion of our shared cultural heritage, modern Homo Sapiens have perfected the art of extinction.

It is a bleak future. One that leaves less and less room for those of us who seek freedom and justice. It is a world that has been reduced to cultural poverty by traditions and tragedies alike.

It is a world where all life on Earth has been reduced to interchangeable and disposable parts in the pursuit of Progress. It is a world filled with death and injustice, but it is also falling apart.

Whether humans can survive this collapse of our own making is yet to be determined. It will be hard, but even the strongest rock is defeated by water and wind in the end. It is in these cracks and fissures that we can seek our refuge. The spots forgotten about and overlooked. The areas where literal and figurative weeds grow. The edges. The TAZs where humanity still flourish.

Go on hikes. Hunt mushrooms. Raise bees. Raise Kids. Bake bread. Love. Hate. Grow some carrots. Chop some wood. Pull some weeds. Laugh. Hug a puppy. Cry. Resist! Grow. Take a nap. Rise up! Read a book. Lend a hand. Take notes. Have fun. Fish. Visit a friend. Hug your mom. Plant trees. Be human….

.