SUBHEAD: Text of GMO label bill includes a definition of bioengineering that critics disagree with.

By Lindsey Wise on 1 July 2016 for Miami Herald -

(http://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/article87197417.html)

Image above: Some packaged foods are voluntarily labeled as being free of GMO at the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-Op in Sacramento on Sept. 18, 2012. From original article.

[IB Publisher's Note: This bill is what used to be called "The Big Runaround". It's a bunch of bullshit to avoid dealing with the real problem - in fact it's to avoid even admitting there is a problem. Note that meat is not included in the labeling bill. This is significant because virtually all commercial food used to raise farm fed beef, pork, chicken and fish relies on GMO corn for feed. The American Bread Basket has been totally taken over by genetic modification of seeds, dependence on pesticides, reliance on synthetic fertilizer and other environmentally destructive practices. Big Ag is approaching a dead end. They know they are doomed... especially if the public comes to realize what they are doing to our food.]

“There may be no genetically engineered food that we commonly eat that’s actually covered by this law as it’s currently written,” said Jean Halloran of Consumers Union, the policy arm of Consumer Reports. “I have to think that that’s a drafting error, but nobody’s said they’re going to fix it.”

The bipartisan compromise bill, negotiated last month by the Republican chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee, Pat Roberts of Kansas, and the panel’s top Democrat, Sen. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, is on the verge of passing the U.S. Senate this month. Next it will go to the U.S. House of Representatives, where it’s expected to face little resistance.

The bill would require producers to identify foods that contain genetically modified ingredients with text on packages, a symbol or a link to a website with a QR code, a bar code that can be scanned on a smart phone.

But the legislation contains several sentences that “raise confusion,” according to a June 27 memo to lawmakers from the Food and Drug Administration, which has long maintained that GMOs are safe to eat, and therefore do not need to be labeled.

In the memo, the FDA noted that one paragraph in the Roberts-Stabenow bill narrowly defines bioengineered food as containing “genetic material,” which could exclude many products made from bioengineered crops, such as refined sugars, oils and starches.

The bill’s language also would limit coverage to foods where the genetic modification “could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature,” a standard that could be hard to prove, the agency said.

Halloran said consumer groups are scrambling to bring lawmakers attention to these concerns before an expected vote July 13.

“It was brought forward so quickly without a hearing or much review, and it took us a while to tussle through what it actually says, so I think it hasn’t gotten the kind of serious scrutiny that it needs,” she said.

A coalition of nearly 70 consumer groups and organic farming associations has sent a letter urging senators to oppose the legislation, calling it “a non-labeling bill under the guise of a mandatory labeling bill.”

The letter estimates that 99 percent of all GMO food ultimately could be exempt from labeling since the bill leaves it up to a future Secretary of Agriculture to decide how much GMO content in a food qualifies it for labeling. “If that secretary were to decide on a high percentage of GMO content, it would exempt virtually all processed GMO foods,” the letter said.

Consumer advocates also object to the lack of consequences for companies that fail to properly label their products and the fact that the labels themselves won’t necessarily have to contain the words “GMO,” “genetically modified” or “biotechnology.”

Roberts defended the bill in a statement on Friday.

“All bioengineered food crops currently on the market are captured by the definition of ‘bioengineering,’ ” he said.

Whether that definition also captures refined sugars, oils and other products made from genetically engineered crops, will be determined through rule-making by federal agencies that implement the legislation, said Meghan Cline, a spokeswoman for the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Roberts also took issue with consumer advocates’ criticism that the compromise bill released on June 23 had not been subject to public hearings or testimony.

“This is a good, bipartisan, commonsense way to set a national standard — it’ll give certainty to consumers, and to our producers, without stigmatizing the important use of science,” said Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri, a Democrat who plans to vote for the bill.

For those opposed to the Roberts-Stabenow bill, the fight has taken on particular urgency because the federal legislation would nullify any state laws that require GMO labeling.

The first such law in the nation went into effect in Vermont on July 1.

Fresh off the campaign trail, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has vowed to do everything he can to defeat the Roberts-Stabenow bill.

From the steps of the statehouse in Montpelier, Vermont, on Friday, Sanders said he and other members of Congress would not allow Vermont’s law to be overturned by bad federal legislation.

Sanders said the Roberts-Stabenow bill “would create a confusing, misleading and unenforceable national standard” for GMO labeling.

The major agribusiness and biotech companies “do not believe people have a right to know what’s in the food they eat,” Sanders said. “That is why they have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in lobbying and campaign contributions to overturn the GMO right-to-know legislation that states have already passed and that many other states are on the verge of passing.”

Voluntary GMO labeling grows

SUBHEAD: Campbell's, is calling on the federal government to create a mandatory labeling law.

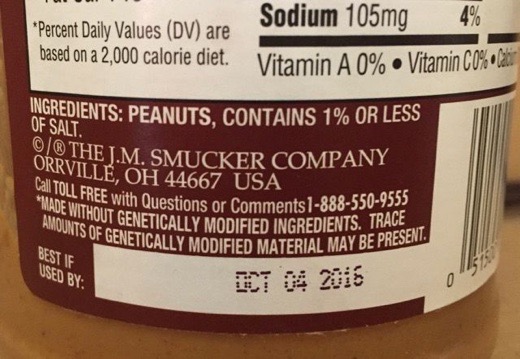

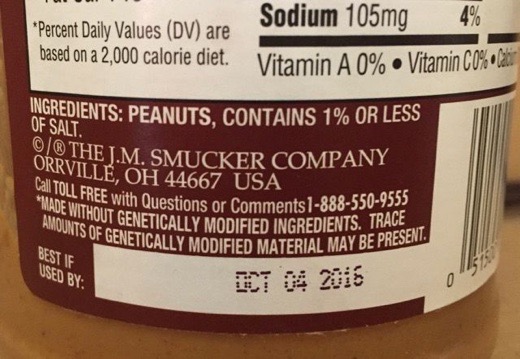

Image above: "MADE WITHOUT GENETICALLY MODIFIED INGREDIENTS> TRACE AMOUNTS OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED MATERIAL MAY BE PRESENT". If this is the case of many food products the truth about GMO ingredients will be fuzzy around the edges. From original article.

It's been less than a month since the Senate stopped an anti-GMO labeling act from becoming law which would have banned individual states from requiring GMO labeling on foods. Since the law did not pass, it looks like Vermont's GMO labeling law will be enacted as planned this July.

The law will require food manufacturers that use GMOs in their foods to label them as such if the foods are sold in Vermont. This creates a problem for the food manufacturers. Do they create one label for Vermont and another label for the rest of the country? What happens if a second state creates a law that require different wording than Vermont's? Do the food manufacturers now have to have three different labels?

That problem could be solved by the federal government creating a standard that requires clear, mandatory labeling on the package. Earlier this year Campbell's broke with the rest of the major food manufacturers and called on the federal government to create a standard for the entire U.S. Campbell's made this announcement before the Senate voted down the anti-GMO labeling bill, in hopes to avoid a "patchwork of state-by-state labeling laws" that they believe would create consumer confusion.

Other big food manufacturers must have been hoping for the Senate to pass the law, but planning for its defeat. In the days following the defeat, several of them made announcements that they would begin to label foods with GMOs, even though they stand by the safety of genetically modified ingredients.

Just two days after the bill failed to gain the votes it needed to pass, General Mills announced it would begin to label GMOs on all its products, not just the ones in Vermont. The company announced they would label nationally because labeling products just in one state would cost consumers too much money. In the next week or two after that, several other companies made similar announcements.

On March 22, ConAgra said it's urging Congress to pass a national solution to GMO labeling as quickly as possible. Until then it will begin to nationally label GMOs because state-by-state labeling laws would cause "significant complications and costs for food companies."

On March 23, Kellogg's released a statement from North American President Paul Norman who said the company would like a federal solution, but until then "in order to comply with Vermont’s labeling law, we will start labeling some of our products nationwide for the presence of GMOs beginning in mid-to-late April. We chose nationwide labeling because a special label for Vermont would be logistically unmanageable and even more costly for us and our consumers."

Mars also has an undated statement on its website in response to the Vermont law. "To comply with that law, Mars is introducing clear, on-pack labeling on our products that contain GM ingredients nationwide."

Only one of these five big food companies, Campbell's, is calling on the federal government to create a mandatory labeling law. The federal or national solution that General Mills, ConAgra and Kellogg's would like is not necessarily a mandatory labeling law. A national solution that would satisfy them would be the same national solution that was in the anti-GMO labeling bill that was struck down — one where the government sets standards for voluntary labeling and states would not be allowed to legally require labeling.

Until we have a national, mandatory GMO labeling law, the possibility of big food companies adding these voluntary labels to their packaging while continuing to pour money into fighting labeling laws is very real. For those who want GMO labels on all foods to be on them indefinitely, the fight is not over yet.

.

By Lindsey Wise on 1 July 2016 for Miami Herald -

(http://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/article87197417.html)

Image above: Some packaged foods are voluntarily labeled as being free of GMO at the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-Op in Sacramento on Sept. 18, 2012. From original article.

[IB Publisher's Note: This bill is what used to be called "The Big Runaround". It's a bunch of bullshit to avoid dealing with the real problem - in fact it's to avoid even admitting there is a problem. Note that meat is not included in the labeling bill. This is significant because virtually all commercial food used to raise farm fed beef, pork, chicken and fish relies on GMO corn for feed. The American Bread Basket has been totally taken over by genetic modification of seeds, dependence on pesticides, reliance on synthetic fertilizer and other environmentally destructive practices. Big Ag is approaching a dead end. They know they are doomed... especially if the public comes to realize what they are doing to our food.]

Polls show Americans find the idea of "Frankenfoods" unappetizing and are open to labels identifying which products contain genetically modified ingredients. But some in the scientific community say GMOs are safe. And some anti-hunger advocates say the science behind them can help deliver nourishment to millions living in poverty.A bill to create the first nationwide labeling standard for genetically modified foods is getting push-back from consumer advocates alarmed that its language could exempt a vast majority of foods made with genetic engineering.

- Randall Benton The Sacramento Bee.

“There may be no genetically engineered food that we commonly eat that’s actually covered by this law as it’s currently written,” said Jean Halloran of Consumers Union, the policy arm of Consumer Reports. “I have to think that that’s a drafting error, but nobody’s said they’re going to fix it.”

The bipartisan compromise bill, negotiated last month by the Republican chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee, Pat Roberts of Kansas, and the panel’s top Democrat, Sen. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, is on the verge of passing the U.S. Senate this month. Next it will go to the U.S. House of Representatives, where it’s expected to face little resistance.

The bill would require producers to identify foods that contain genetically modified ingredients with text on packages, a symbol or a link to a website with a QR code, a bar code that can be scanned on a smart phone.

But the legislation contains several sentences that “raise confusion,” according to a June 27 memo to lawmakers from the Food and Drug Administration, which has long maintained that GMOs are safe to eat, and therefore do not need to be labeled.

In the memo, the FDA noted that one paragraph in the Roberts-Stabenow bill narrowly defines bioengineered food as containing “genetic material,” which could exclude many products made from bioengineered crops, such as refined sugars, oils and starches.

The bill’s language also would limit coverage to foods where the genetic modification “could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature,” a standard that could be hard to prove, the agency said.

Halloran said consumer groups are scrambling to bring lawmakers attention to these concerns before an expected vote July 13.

“It was brought forward so quickly without a hearing or much review, and it took us a while to tussle through what it actually says, so I think it hasn’t gotten the kind of serious scrutiny that it needs,” she said.

A coalition of nearly 70 consumer groups and organic farming associations has sent a letter urging senators to oppose the legislation, calling it “a non-labeling bill under the guise of a mandatory labeling bill.”

The letter estimates that 99 percent of all GMO food ultimately could be exempt from labeling since the bill leaves it up to a future Secretary of Agriculture to decide how much GMO content in a food qualifies it for labeling. “If that secretary were to decide on a high percentage of GMO content, it would exempt virtually all processed GMO foods,” the letter said.

Consumer advocates also object to the lack of consequences for companies that fail to properly label their products and the fact that the labels themselves won’t necessarily have to contain the words “GMO,” “genetically modified” or “biotechnology.”

Roberts defended the bill in a statement on Friday.

“All bioengineered food crops currently on the market are captured by the definition of ‘bioengineering,’ ” he said.

Whether that definition also captures refined sugars, oils and other products made from genetically engineered crops, will be determined through rule-making by federal agencies that implement the legislation, said Meghan Cline, a spokeswoman for the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Roberts also took issue with consumer advocates’ criticism that the compromise bill released on June 23 had not been subject to public hearings or testimony.

“We held a hearing last October that covered all facets of agriculture biotechnology, including labeling,” Roberts said. “To say we have not been transparent in this process is simply incorrect.The bill is likely to pass in the Senate, where it received 68 votes to overcome a procedural hurdle on Wednesday.

Myself, and members of the Agriculture Committee, have listened to constituents from all sides of this debate and crafted the best piece of legislation that allows farmers to keep using safe technology on the farm while satisfying consumers’ (desire) to know what’s in their food.”

“This is a good, bipartisan, commonsense way to set a national standard — it’ll give certainty to consumers, and to our producers, without stigmatizing the important use of science,” said Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri, a Democrat who plans to vote for the bill.

For those opposed to the Roberts-Stabenow bill, the fight has taken on particular urgency because the federal legislation would nullify any state laws that require GMO labeling.

The first such law in the nation went into effect in Vermont on July 1.

Fresh off the campaign trail, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders has vowed to do everything he can to defeat the Roberts-Stabenow bill.

From the steps of the statehouse in Montpelier, Vermont, on Friday, Sanders said he and other members of Congress would not allow Vermont’s law to be overturned by bad federal legislation.

Sanders said the Roberts-Stabenow bill “would create a confusing, misleading and unenforceable national standard” for GMO labeling.

The major agribusiness and biotech companies “do not believe people have a right to know what’s in the food they eat,” Sanders said. “That is why they have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in lobbying and campaign contributions to overturn the GMO right-to-know legislation that states have already passed and that many other states are on the verge of passing.”

Voluntary GMO labeling grows

SUBHEAD: Campbell's, is calling on the federal government to create a mandatory labeling law.

Image above: "MADE WITHOUT GENETICALLY MODIFIED INGREDIENTS> TRACE AMOUNTS OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED MATERIAL MAY BE PRESENT". If this is the case of many food products the truth about GMO ingredients will be fuzzy around the edges. From original article.

It's been less than a month since the Senate stopped an anti-GMO labeling act from becoming law which would have banned individual states from requiring GMO labeling on foods. Since the law did not pass, it looks like Vermont's GMO labeling law will be enacted as planned this July.

The law will require food manufacturers that use GMOs in their foods to label them as such if the foods are sold in Vermont. This creates a problem for the food manufacturers. Do they create one label for Vermont and another label for the rest of the country? What happens if a second state creates a law that require different wording than Vermont's? Do the food manufacturers now have to have three different labels?

That problem could be solved by the federal government creating a standard that requires clear, mandatory labeling on the package. Earlier this year Campbell's broke with the rest of the major food manufacturers and called on the federal government to create a standard for the entire U.S. Campbell's made this announcement before the Senate voted down the anti-GMO labeling bill, in hopes to avoid a "patchwork of state-by-state labeling laws" that they believe would create consumer confusion.

Other big food manufacturers must have been hoping for the Senate to pass the law, but planning for its defeat. In the days following the defeat, several of them made announcements that they would begin to label foods with GMOs, even though they stand by the safety of genetically modified ingredients.

Just two days after the bill failed to gain the votes it needed to pass, General Mills announced it would begin to label GMOs on all its products, not just the ones in Vermont. The company announced they would label nationally because labeling products just in one state would cost consumers too much money. In the next week or two after that, several other companies made similar announcements.

On March 22, ConAgra said it's urging Congress to pass a national solution to GMO labeling as quickly as possible. Until then it will begin to nationally label GMOs because state-by-state labeling laws would cause "significant complications and costs for food companies."

On March 23, Kellogg's released a statement from North American President Paul Norman who said the company would like a federal solution, but until then "in order to comply with Vermont’s labeling law, we will start labeling some of our products nationwide for the presence of GMOs beginning in mid-to-late April. We chose nationwide labeling because a special label for Vermont would be logistically unmanageable and even more costly for us and our consumers."

Mars also has an undated statement on its website in response to the Vermont law. "To comply with that law, Mars is introducing clear, on-pack labeling on our products that contain GM ingredients nationwide."

Only one of these five big food companies, Campbell's, is calling on the federal government to create a mandatory labeling law. The federal or national solution that General Mills, ConAgra and Kellogg's would like is not necessarily a mandatory labeling law. A national solution that would satisfy them would be the same national solution that was in the anti-GMO labeling bill that was struck down — one where the government sets standards for voluntary labeling and states would not be allowed to legally require labeling.

Until we have a national, mandatory GMO labeling law, the possibility of big food companies adding these voluntary labels to their packaging while continuing to pour money into fighting labeling laws is very real. For those who want GMO labels on all foods to be on them indefinitely, the fight is not over yet.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment