SUBHEAD: The Saudi led debacle in Doha will be seen as marking the beginning of the end of the old oil order.

By Michael Klare on 28 April 2016 for Tom Dispatch -

(http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/176134/tomgram%3A_michael_klare%2C_the_coming_world_of_%22peak_oil_demand%2C%22_not_%22peak_oil%22/)

Image above: Skyscrapers in the city of Doha, Qatar. From (http://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-04-29/the-debacle-at-doha).

Sunday, April 17th was the designated moment. The world’s leading oil producers were expected to bring fresh discipline to the chaotic petroleum market and spark a return to high prices.

Meeting in Doha, the glittering capital of petroleum-rich Qatar, the oil ministers of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), along with such key non-OPEC producers as Russia and Mexico, were scheduled to ratify a draft agreement obliging them to freeze their oil output at current levels.

In anticipation of such a deal, oil prices had begun to creep inexorably upward, from $30 per barrel in mid-January to $43 on the eve of the gathering. But far from restoring the old oil order, the meeting ended in discord, driving prices down again and revealing deep cracks in the ranks of global energy producers.

It is hard to overstate the significance of the Doha debacle. At the very least, it will perpetuate the low oil prices that have plagued the industry for the past two years, forcing smaller firms into bankruptcy and erasing hundreds of billions of dollars of investments in new production capacity. It may also have obliterated any future prospects for cooperation between OPEC and non-OPEC producers in regulating the market.

Most of all, however, it demonstrated that the petroleum-fueled world we’ve known these last decades -- with oil demand always thrusting ahead of supply, ensuring steady profits for all major producers -- is no more. Replacing it is an anemic, possibly even declining, demand for oil that is likely to force suppliers to fight one another for ever-diminishing market shares.

The Road to Doha

Before the Doha gathering, the leaders of the major producing countries expressed confidence that a production freeze would finally halt the devastating slump in oil prices that began in mid-2014. Most of them are heavily dependent on petroleum exports to finance their governments and keep restiveness among their populaces at bay.

Both Russia and Venezuela, for instance, rely on energy exports for approximately 50% of government income, while for Nigeria it’s more like 75%. So the plunge in prices had already cut deep into government spending around the world, causing civil unrest and even in some cases political turmoil.

No one expected the April 17th meeting to result in an immediate, dramatic price upturn, but everyone hoped that it would lay the foundation for a steady rise in the coming months. The leaders of these countries were well aware of one thing: to achieve such progress, unity was crucial.

Otherwise they were not likely to overcome the various factors that had caused the price collapse in the first place. Some of these were structural and embedded deep in the way the industry had been organized; some were the product of their own feckless responses to the crisis.

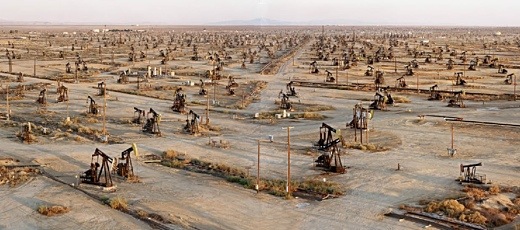

On the structural side, global demand for energy had, in recent years, ceased to rise quickly enough to soak up all the crude oil pouring onto the market, thanks in part to new supplies from Iraq and especially from the expanding shale fields of the United States.

This oversupply triggered the initial 2014 price drop when Brent crude -- the international benchmark blend -- went from a high of $115 on June 19th to $77 on November 26th, the day before a fateful OPEC meeting in Vienna. The next day, OPEC members, led by Saudi Arabia, failed to agree on either production cuts or a freeze, and the price of oil went into freefall.

The failure of that November meeting has been widely attributed to the Saudis’ desire to kill off new output elsewhere -- especially shale production in the United States -- and to restore their historic dominance of the global oil market. Many analysts were also convinced that Riyadh was seeking to punish regional rivals Iran and Russia for their support of the Assad regime in Syria (which the Saudis seek to topple).

The rejection, in other words, was meant to fulfill two tasks at the same time: blunt or wipe out the challenge posed by North American shale producers and undermine two economically shaky energy powers that opposed Saudi goals in the Middle East by depriving them of much needed oil revenues.

Because Saudi Arabia could produce oil so much more cheaply than other countries -- for as little as $3 per barrel -- and because it could draw upon hundreds of billions of dollars in sovereign wealth funds to meet any budget shortfalls of its own, its leaders believed it more capable of weathering any price downturn than its rivals.

Today, however, that rosy prediction is looking grimmer as the Saudi royals begin to feel the pinch of low oil prices, and find themselves cutting back on the benefits they had been passing on to an ever-growing, potentially restive population while still financing a costly, inconclusive, and increasingly disastrous war in Yemen.

Many energy analysts became convinced that Doha would prove the decisive moment when Riyadh would finally be amenable to a production freeze. Just days before the conference, participants expressed growing confidence that such a plan would indeed be adopted.

After all, preliminary negotiations between Russia, Venezuela, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia had produced a draft document that most participants assumed was essentially ready for signature. The only sticking point: the nature of Iran’s participation.

The Iranians were, in fact, agreeable to such a freeze, but only after they were allowed to raise their relatively modest daily output to levels achieved in 2012 before the West imposed sanctions in an effort to force Tehran to agree to dismantle its nuclear enrichment program. Now that those sanctions were, in fact, being lifted as a result of the recently concluded nuclear deal, Tehran was determined to restore the status quo ante.

On this, the Saudis balked, having no wish to see their arch-rival obtain added oil revenues. Still, most observers assumed that, in the end, Riyadh would agree to a formula allowing Iran some increase before a freeze.

“There are positive indications an agreement will be reached during this meeting... an initial agreement on freezing production,” said Nawal Al-Fuzaia, Kuwait’s OPEC representative, echoing the views of other Doha participants.

But then something happened. According to people familiar with the sequence of events, Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Crown Prince and key oil strategist, Mohammed bin Salman, called the Saudi delegation in Doha at 3:00 a.m. on April 17th and instructed them to spurn a deal that provided leeway of any sort for Iran.

When the Iranians -- who chose not to attend the meeting -- signaled that they had no intention of freezing their output to satisfy their rivals, the Saudis rejected the draft agreement it had helped negotiate and the assembly ended in disarray.

Geopolitics to the Fore

Most analysts have since suggested that the Saudi royals simply considered punishing Iran more important than raising oil prices. No matter the cost to them, in other words, they could not bring themselves to help Iran pursue its geopolitical objectives, including giving yet more support to Shiite forces in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon.

Already feeling pressured by Tehran and ever less confident of Washington’s support, they were ready to use any means available to weaken the Iranians, whatever the danger to themselves.

“The failure to reach an agreement in Doha is a reminder that Saudi Arabia is in no mood to do Iran any favors right now and that their ongoing geopolitical conflict cannot be discounted as an element of the current Saudi oil policy,” said Jason Bordoff of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

Many analysts also pointed to the rising influence of Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, entrusted with near-total control of the economy and the military by his aging father, King Salman. As Minister of Defense, the prince has spearheaded the Saudi drive to counter the Iranians in a regional struggle for dominance.

Most significantly, he is the main force behind Saudi Arabia’s ongoing intervention in Yemen, aimed at defeating the Houthi rebels, a largely Shia group with loose ties to Iran, and restoring deposed former president Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi.

After a year of relentless U.S.-backed airstrikes (including the use of cluster bombs), the Saudi intervention has, in fact, failed to achieve its intended objectives, though it has produced thousands of civilian casualties, provoking fierce condemnation from U.N. officials, and created space for the rise of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Nevertheless, the prince seems determined to keep the conflict going and to counter Iranian influence across the region.

For Prince Mohammed, the oil market has evidently become just another arena for this ongoing struggle. “Under his guidance,” the Financial Times noted in April, “Saudi Arabia’s oil policy appears to be less driven by the price of crude than global politics, particularly Riyadh’s bitter rivalry with post-sanctions Tehran.”

This seems to have been the backstory for Riyadh’s last-minute decision to scuttle the talks in Doha. On April 16th, for instance, Prince Mohammed couldn’t have been blunter to Bloomberg, even if he didn’t mention the Iranians by name: “If all major producers don’t freeze production, we will not freeze production.”

With the proposed agreement in tatters, Saudi Arabia is now expected to boost its own output, ensuring that prices will remain bargain-basement low and so deprive Iran of any windfall from its expected increase in exports.

The kingdom, Prince Mohammed told Bloomberg, was prepared to immediately raise production from its current 10.2 million barrels per day to 11.5 million barrels and could add another million barrels “if we wanted to” in the next six to nine months.

With Iranian and Iraqi oil heading for market in larger quantities, that’s the definition of oversupply. It would certainly ensure Saudi Arabia’s continued dominance of the market, but it might also wound the kingdom in a major way, if not fatally.

A New Global Reality

No doubt geopolitics played a significant role in the Saudi decision, but that’s hardly the whole story.

Overshadowing discussions about a possible production freeze was a new fact of life for the oil industry: the past would be no predictor of the future when it came to global oil demand. Whatever the Saudis think of the Iranians or vice versa, their industry is being fundamentally transformed, altering relationships among the major producers and eroding their inclination to cooperate.

Until very recently, it was assumed that the demand for oil would continue to expand indefinitely, creating space for multiple producers to enter the market, and for ones already in it to increase their output.

Even when supply outran demand and drove prices down, as has periodically occurred, producers could always take solace in the knowledge that, as in the past, demand would eventually rebound, jacking prices up again. Under such circumstances and at such a moment, it was just good sense for individual producers to cooperate in lowering output, knowing that everyone would benefit sooner or later from the inevitable price increase.

But what happens if confidence in the eventual resurgence of demand begins to wither? Then the incentives to cooperate begin to evaporate, too, and it’s every producer for itself in a mad scramble to protect market share.

This new reality -- a world in which “peak oil demand,” rather than “peak oil,” will shape the consciousness of major players -- is what the Doha catastrophe foreshadowed.

At the beginning of this century, many energy analysts were convinced that we were at the edge of the arrival of “peak oil”; a peak, that is, in the output of petroleum in which planetary reserves would be exhausted long before the demand for oil disappeared, triggering a global economic crisis. As a result of advances in drilling technology, however, the supply of oil has continued to grow, while demand has unexpectedly begun to stall.

This can be traced both to slowing economic growth globally and to an accelerating “green revolution” in which the planet will be transitioning to non-carbon fuel sources. With most nations now committed to measures aimed at reducing emissions of greenhouse gases under the just-signed Paris climate accord, the demand for oil is likely to experience significant declines in the years ahead. In other words, global oil demand will peak long before supplies begin to run low, creating a monumental challenge for the oil-producing countries.

This is no theoretical construct. It’s reality itself. Net consumption of oil in the advanced industrialized nations has already dropped from 50 million barrels per day in 2005 to 45 million barrels in 2014. Further declines are in store as strict fuel efficiency standards for the production of new vehicles and other climate-related measures take effect, the price of solar and wind power continues to fall, and other alternative energy sources come on line.

While the demand for oil does continue to rise in the developing world, even there it’s not climbing at rates previously taken for granted. With such countries also beginning to impose tougher constraints on carbon emissions, global consumption is expected to reach a peak and begin an inexorable decline. According to experts Thijs Van de Graaf and Aviel Verbruggen, overall world peak demand could be reached as early as 2020.

In such a world, high-cost oil producers will be driven out of the market and the advantage -- such as it is -- will lie with the lowest-cost ones. Countries that depend on petroleum exports for a large share of their revenues will come under increasing pressure to move away from excessive reliance on oil.

This may have been another consideration in the Saudi decision at Doha. In the months leading up to the April meeting, senior Saudi officials dropped hints that they were beginning to plan for a post-petroleum era and that Deputy Crown Prince bin Salman would play a key role in overseeing the transition.

On April 1st, the prince himself indicated that steps were underway to begin this process. As part of the effort, he announced, he was planning an initial public offering of shares in state-owned Saudi Aramco, the world’s number one oil producer, and would transfer the proceeds, an estimated $2 trillion, to its Public Investment Fund (PIF).

“IPOing Aramco and transferring its shares to PIF will technically make investments the source of Saudi government revenue, not oil,” the prince pointed out. “What is left now is to diversify investments. So within 20 years, we will be an economy or state that doesn’t depend mainly on oil.”

For a country that more than any other has rested its claim to wealth and power on the production and sale of petroleum, this is a revolutionary statement. If Saudi Arabia says it is ready to begin a move away from reliance on petroleum, we are indeed entering a new world in which, among other things, the titans of oil production will no longer hold sway over our lives as they have in the past.

This, in fact, appears to be the outlook adopted by Prince Mohammed in the wake of the Doha debacle. In announcing the kingdom’s new economic blueprint on April 25th, he vowed to liberate the country from its “addiction” to oil.” This will not, of course, be easy to achieve, given the kingdom’s heavy reliance on oil revenues and lack of plausible alternatives.

The 30-year-old prince could also face opposition from within the royal family to his audacious moves (as well as his blundering ones in Yemen and possibly elsewhere). Whatever the fate of the Saudi royals, however, if predictions of a future peak in world oil demand prove accurate, the debacle in Doha will be seen as marking the beginning of the end of the old oil order.

• Michael T. Klare, a TomDispatch regular, is a professor of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and the author, most recently, of The Race for What’s Left. A documentary movie version of his book Blood and Oil is available from the Media Education Foundation. Follow him on Twitter at @mklare1.

.

By Michael Klare on 28 April 2016 for Tom Dispatch -

(http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/176134/tomgram%3A_michael_klare%2C_the_coming_world_of_%22peak_oil_demand%2C%22_not_%22peak_oil%22/)

Image above: Skyscrapers in the city of Doha, Qatar. From (http://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-04-29/the-debacle-at-doha).

Sunday, April 17th was the designated moment. The world’s leading oil producers were expected to bring fresh discipline to the chaotic petroleum market and spark a return to high prices.

Meeting in Doha, the glittering capital of petroleum-rich Qatar, the oil ministers of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), along with such key non-OPEC producers as Russia and Mexico, were scheduled to ratify a draft agreement obliging them to freeze their oil output at current levels.

In anticipation of such a deal, oil prices had begun to creep inexorably upward, from $30 per barrel in mid-January to $43 on the eve of the gathering. But far from restoring the old oil order, the meeting ended in discord, driving prices down again and revealing deep cracks in the ranks of global energy producers.

It is hard to overstate the significance of the Doha debacle. At the very least, it will perpetuate the low oil prices that have plagued the industry for the past two years, forcing smaller firms into bankruptcy and erasing hundreds of billions of dollars of investments in new production capacity. It may also have obliterated any future prospects for cooperation between OPEC and non-OPEC producers in regulating the market.

Most of all, however, it demonstrated that the petroleum-fueled world we’ve known these last decades -- with oil demand always thrusting ahead of supply, ensuring steady profits for all major producers -- is no more. Replacing it is an anemic, possibly even declining, demand for oil that is likely to force suppliers to fight one another for ever-diminishing market shares.

The Road to Doha

Before the Doha gathering, the leaders of the major producing countries expressed confidence that a production freeze would finally halt the devastating slump in oil prices that began in mid-2014. Most of them are heavily dependent on petroleum exports to finance their governments and keep restiveness among their populaces at bay.

Both Russia and Venezuela, for instance, rely on energy exports for approximately 50% of government income, while for Nigeria it’s more like 75%. So the plunge in prices had already cut deep into government spending around the world, causing civil unrest and even in some cases political turmoil.

No one expected the April 17th meeting to result in an immediate, dramatic price upturn, but everyone hoped that it would lay the foundation for a steady rise in the coming months. The leaders of these countries were well aware of one thing: to achieve such progress, unity was crucial.

Otherwise they were not likely to overcome the various factors that had caused the price collapse in the first place. Some of these were structural and embedded deep in the way the industry had been organized; some were the product of their own feckless responses to the crisis.

On the structural side, global demand for energy had, in recent years, ceased to rise quickly enough to soak up all the crude oil pouring onto the market, thanks in part to new supplies from Iraq and especially from the expanding shale fields of the United States.

This oversupply triggered the initial 2014 price drop when Brent crude -- the international benchmark blend -- went from a high of $115 on June 19th to $77 on November 26th, the day before a fateful OPEC meeting in Vienna. The next day, OPEC members, led by Saudi Arabia, failed to agree on either production cuts or a freeze, and the price of oil went into freefall.

The failure of that November meeting has been widely attributed to the Saudis’ desire to kill off new output elsewhere -- especially shale production in the United States -- and to restore their historic dominance of the global oil market. Many analysts were also convinced that Riyadh was seeking to punish regional rivals Iran and Russia for their support of the Assad regime in Syria (which the Saudis seek to topple).

The rejection, in other words, was meant to fulfill two tasks at the same time: blunt or wipe out the challenge posed by North American shale producers and undermine two economically shaky energy powers that opposed Saudi goals in the Middle East by depriving them of much needed oil revenues.

Because Saudi Arabia could produce oil so much more cheaply than other countries -- for as little as $3 per barrel -- and because it could draw upon hundreds of billions of dollars in sovereign wealth funds to meet any budget shortfalls of its own, its leaders believed it more capable of weathering any price downturn than its rivals.

Today, however, that rosy prediction is looking grimmer as the Saudi royals begin to feel the pinch of low oil prices, and find themselves cutting back on the benefits they had been passing on to an ever-growing, potentially restive population while still financing a costly, inconclusive, and increasingly disastrous war in Yemen.

Many energy analysts became convinced that Doha would prove the decisive moment when Riyadh would finally be amenable to a production freeze. Just days before the conference, participants expressed growing confidence that such a plan would indeed be adopted.

After all, preliminary negotiations between Russia, Venezuela, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia had produced a draft document that most participants assumed was essentially ready for signature. The only sticking point: the nature of Iran’s participation.

The Iranians were, in fact, agreeable to such a freeze, but only after they were allowed to raise their relatively modest daily output to levels achieved in 2012 before the West imposed sanctions in an effort to force Tehran to agree to dismantle its nuclear enrichment program. Now that those sanctions were, in fact, being lifted as a result of the recently concluded nuclear deal, Tehran was determined to restore the status quo ante.

On this, the Saudis balked, having no wish to see their arch-rival obtain added oil revenues. Still, most observers assumed that, in the end, Riyadh would agree to a formula allowing Iran some increase before a freeze.

“There are positive indications an agreement will be reached during this meeting... an initial agreement on freezing production,” said Nawal Al-Fuzaia, Kuwait’s OPEC representative, echoing the views of other Doha participants.

But then something happened. According to people familiar with the sequence of events, Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Crown Prince and key oil strategist, Mohammed bin Salman, called the Saudi delegation in Doha at 3:00 a.m. on April 17th and instructed them to spurn a deal that provided leeway of any sort for Iran.

When the Iranians -- who chose not to attend the meeting -- signaled that they had no intention of freezing their output to satisfy their rivals, the Saudis rejected the draft agreement it had helped negotiate and the assembly ended in disarray.

Geopolitics to the Fore

Most analysts have since suggested that the Saudi royals simply considered punishing Iran more important than raising oil prices. No matter the cost to them, in other words, they could not bring themselves to help Iran pursue its geopolitical objectives, including giving yet more support to Shiite forces in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon.

Already feeling pressured by Tehran and ever less confident of Washington’s support, they were ready to use any means available to weaken the Iranians, whatever the danger to themselves.

“The failure to reach an agreement in Doha is a reminder that Saudi Arabia is in no mood to do Iran any favors right now and that their ongoing geopolitical conflict cannot be discounted as an element of the current Saudi oil policy,” said Jason Bordoff of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

Many analysts also pointed to the rising influence of Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, entrusted with near-total control of the economy and the military by his aging father, King Salman. As Minister of Defense, the prince has spearheaded the Saudi drive to counter the Iranians in a regional struggle for dominance.

Most significantly, he is the main force behind Saudi Arabia’s ongoing intervention in Yemen, aimed at defeating the Houthi rebels, a largely Shia group with loose ties to Iran, and restoring deposed former president Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi.

After a year of relentless U.S.-backed airstrikes (including the use of cluster bombs), the Saudi intervention has, in fact, failed to achieve its intended objectives, though it has produced thousands of civilian casualties, provoking fierce condemnation from U.N. officials, and created space for the rise of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Nevertheless, the prince seems determined to keep the conflict going and to counter Iranian influence across the region.

For Prince Mohammed, the oil market has evidently become just another arena for this ongoing struggle. “Under his guidance,” the Financial Times noted in April, “Saudi Arabia’s oil policy appears to be less driven by the price of crude than global politics, particularly Riyadh’s bitter rivalry with post-sanctions Tehran.”

This seems to have been the backstory for Riyadh’s last-minute decision to scuttle the talks in Doha. On April 16th, for instance, Prince Mohammed couldn’t have been blunter to Bloomberg, even if he didn’t mention the Iranians by name: “If all major producers don’t freeze production, we will not freeze production.”

With the proposed agreement in tatters, Saudi Arabia is now expected to boost its own output, ensuring that prices will remain bargain-basement low and so deprive Iran of any windfall from its expected increase in exports.

The kingdom, Prince Mohammed told Bloomberg, was prepared to immediately raise production from its current 10.2 million barrels per day to 11.5 million barrels and could add another million barrels “if we wanted to” in the next six to nine months.

With Iranian and Iraqi oil heading for market in larger quantities, that’s the definition of oversupply. It would certainly ensure Saudi Arabia’s continued dominance of the market, but it might also wound the kingdom in a major way, if not fatally.

A New Global Reality

No doubt geopolitics played a significant role in the Saudi decision, but that’s hardly the whole story.

Overshadowing discussions about a possible production freeze was a new fact of life for the oil industry: the past would be no predictor of the future when it came to global oil demand. Whatever the Saudis think of the Iranians or vice versa, their industry is being fundamentally transformed, altering relationships among the major producers and eroding their inclination to cooperate.

Until very recently, it was assumed that the demand for oil would continue to expand indefinitely, creating space for multiple producers to enter the market, and for ones already in it to increase their output.

Even when supply outran demand and drove prices down, as has periodically occurred, producers could always take solace in the knowledge that, as in the past, demand would eventually rebound, jacking prices up again. Under such circumstances and at such a moment, it was just good sense for individual producers to cooperate in lowering output, knowing that everyone would benefit sooner or later from the inevitable price increase.

But what happens if confidence in the eventual resurgence of demand begins to wither? Then the incentives to cooperate begin to evaporate, too, and it’s every producer for itself in a mad scramble to protect market share.

This new reality -- a world in which “peak oil demand,” rather than “peak oil,” will shape the consciousness of major players -- is what the Doha catastrophe foreshadowed.

At the beginning of this century, many energy analysts were convinced that we were at the edge of the arrival of “peak oil”; a peak, that is, in the output of petroleum in which planetary reserves would be exhausted long before the demand for oil disappeared, triggering a global economic crisis. As a result of advances in drilling technology, however, the supply of oil has continued to grow, while demand has unexpectedly begun to stall.

This can be traced both to slowing economic growth globally and to an accelerating “green revolution” in which the planet will be transitioning to non-carbon fuel sources. With most nations now committed to measures aimed at reducing emissions of greenhouse gases under the just-signed Paris climate accord, the demand for oil is likely to experience significant declines in the years ahead. In other words, global oil demand will peak long before supplies begin to run low, creating a monumental challenge for the oil-producing countries.

This is no theoretical construct. It’s reality itself. Net consumption of oil in the advanced industrialized nations has already dropped from 50 million barrels per day in 2005 to 45 million barrels in 2014. Further declines are in store as strict fuel efficiency standards for the production of new vehicles and other climate-related measures take effect, the price of solar and wind power continues to fall, and other alternative energy sources come on line.

While the demand for oil does continue to rise in the developing world, even there it’s not climbing at rates previously taken for granted. With such countries also beginning to impose tougher constraints on carbon emissions, global consumption is expected to reach a peak and begin an inexorable decline. According to experts Thijs Van de Graaf and Aviel Verbruggen, overall world peak demand could be reached as early as 2020.

In such a world, high-cost oil producers will be driven out of the market and the advantage -- such as it is -- will lie with the lowest-cost ones. Countries that depend on petroleum exports for a large share of their revenues will come under increasing pressure to move away from excessive reliance on oil.

This may have been another consideration in the Saudi decision at Doha. In the months leading up to the April meeting, senior Saudi officials dropped hints that they were beginning to plan for a post-petroleum era and that Deputy Crown Prince bin Salman would play a key role in overseeing the transition.

On April 1st, the prince himself indicated that steps were underway to begin this process. As part of the effort, he announced, he was planning an initial public offering of shares in state-owned Saudi Aramco, the world’s number one oil producer, and would transfer the proceeds, an estimated $2 trillion, to its Public Investment Fund (PIF).

“IPOing Aramco and transferring its shares to PIF will technically make investments the source of Saudi government revenue, not oil,” the prince pointed out. “What is left now is to diversify investments. So within 20 years, we will be an economy or state that doesn’t depend mainly on oil.”

For a country that more than any other has rested its claim to wealth and power on the production and sale of petroleum, this is a revolutionary statement. If Saudi Arabia says it is ready to begin a move away from reliance on petroleum, we are indeed entering a new world in which, among other things, the titans of oil production will no longer hold sway over our lives as they have in the past.

This, in fact, appears to be the outlook adopted by Prince Mohammed in the wake of the Doha debacle. In announcing the kingdom’s new economic blueprint on April 25th, he vowed to liberate the country from its “addiction” to oil.” This will not, of course, be easy to achieve, given the kingdom’s heavy reliance on oil revenues and lack of plausible alternatives.

The 30-year-old prince could also face opposition from within the royal family to his audacious moves (as well as his blundering ones in Yemen and possibly elsewhere). Whatever the fate of the Saudi royals, however, if predictions of a future peak in world oil demand prove accurate, the debacle in Doha will be seen as marking the beginning of the end of the old oil order.

• Michael T. Klare, a TomDispatch regular, is a professor of peace and world security studies at Hampshire College and the author, most recently, of The Race for What’s Left. A documentary movie version of his book Blood and Oil is available from the Media Education Foundation. Follow him on Twitter at @mklare1.

.