SUBHEAD: This is a decision that will be made in this community, by this community.

By Joan Conrow on 22 June 2011 for Honolulu Weekly -

(http://honoluluweekly.com/cover/2011/06/kauais-hydro-battle)

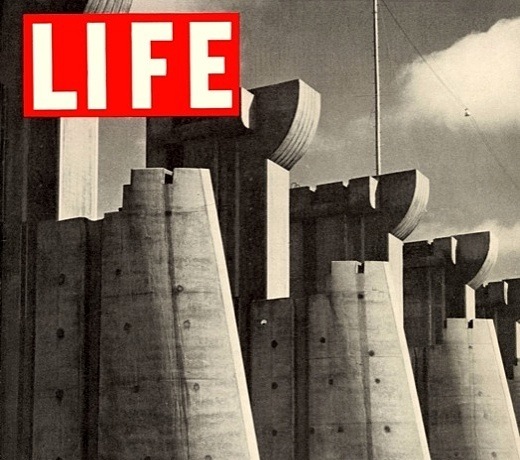

Image above: TVA Fort Peck Dam on cover of the first pictorial Life Magazine on 11/23/1936 From (http://www.milkintheclock.com/2008/11/first-issue-of-life-is-published/).

Hawaii has very strong and nationally recognized protections regarding stream flows and Native Hawaiian rights. That stands to be completely wiped out by what KIUC is doing, and it seems they’re doing it for that purpose. Isaac Moriwake COVER Farmer Jerry Ornellas bristled when he read in the local newspaper that Kauai Island Utility Cooperative (KIUC) was looking to develop a hydroelectric project on the Wailua reservoir. It was the first he’d heard of it, and that rankled, considering he was president of a water users cooperative whose system includes the reservoir.

“They know who we are,” Ornellas said. “You’d think they would have given us the courtesy of a call. But they never said a word.” The Robinson family was equally vexed to discover they had not been consulted on plans to study hydro on land in western Kauai they have owned for more than a century. Conservationists, meanwhile, were outraged to learn that a twice-bitterly-beaten-down plan to dam the Wailua River apparently had been resurrected.

Thus began KIUC’s clumsy foray into hydroelectric development under a federal process that allows investors to stake a claim, gold rush-style, on rivers and irrigation ditches. The utility actually followed the lead of Free Flow Power (FFP), a Massachusetts-based consortium of consultants and investors that filed the permit applications that created a community uproar.

The utility became embroiled when it bought Free Flow’s permits and hired the firm to guide it through a hydro development process administered by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in Washington, DC. It’s a process that has been attempted in Hawaii, but never completed, and Sen. Daniel Akaka has unsuccessfully sought legislation to prevent its use in the Islands. The core concern is whether the FERC process will respect the state’s progressive water code, particularly its instream flow standards, which determine the quantity, flow and depth of water required to protect the various uses of a specific stream.

Others wonder if federal bureaucrats–given their unfamiliarity with Hawaii’s unique cultural, environmental and historical characteristics–can be reasonably expected to set the right standards. Whether or not Hawaii residents can effectively participate in a proceeding based in Washington, DC has yet to be determined. For all those reasons, KIUC’s decision to take the FERC route has raised suspicion and resistance. But the secrecy surrounding the initial applications, and uncertainty about exactly what might be developed, has also fed the opposition.

KIUC claims it is too early to discuss project plans, and regardless of what Free Flow wrote on the applications, it is not going to build any dams. “These permits just give us the right to do feasibility studies,” says David Bissell, chief executive officer of KIUC, a member-owned utility cooperative. “We are just at the very preliminary stages of trying to see what’s possible.”

Hindu Monks Oppose

Not everyone is convinced. “All we have to go on is what’s in their applications,” said Rev. Easan Katir, a monk at Kauai’s Hindu monastery. The monks, who normally eschew political activism, are vigorously opposing the utility’s proposed hydro projects on the Wailua River, which runs through the monastery’s grounds and feeds the East Kauai Water Users Cooperative they helped to form. FERC opponents are leery of both Free Flow and the process that brought it into a relationship with KIUC. “Free Flow Power has never done hydro development,” said Adam Asquith, a taro farmer and Universiy of Hawaii Sea Grant extenson agent on Kauai.

Keeping the Flow

Bissell maintains that the non-profit utility cooperative will benefit from having FFP manage the process, which he says offers insurance that KIUC will not be edged out by a private developer who would charge more for any electricity generated. He also says that without FERC, hydro has no future at KIUC. “I would not recommend we go forward investing possibly millions of dollars without the FERC process because a for-profit developer could jump in front of us,” Bissell said. To stake its own claim, KIUC purchased the shell companies that FFP formed to file six applications on waterways from Hanalei to Kekaha.

FERC has already approved three, giving KIUC preliminary permits that carry the exclusive right to study hydroelectric development for three years. Bissell said no specific price was placed on the applications, which were purchased as part of a larger consulting contract. The utility has refused to disclose the full value of the contract, which includes an incentive for delivering completed projects, but KIUC attorney David Proudfoot said FFP will be paid “several million dollars if none go past the first stage.”

In response, Asquith led a petition drive that is forcing KIUC to put its FFP contract to a vote of its members, with ballots being mailed out this week. Although FERC opponents have little money for advertising, the monastery funded a full-page informational ad in the Kauai newspaper, and citizens have used social media and the Island’s community radio station and public access television station to take their message to co-op members.

Navigating the Waters

Meanwhile, the East Kauai Water Users Cooperative, County of Kauai, Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL) and State Agricultural Development Corporation filed formal petitions to intervene in the FERC permits, and the state attorney general’s office apparently plans to take similar action.

“Why go to Washington, DC, to decide how Hawaii streams are managed?” said William Tam, deputy director of the Hawaii Commission on Water Resources and Management. “It is hard to understand some facts when you’re 5,000 miles away. Written statements do not always tell the whole story.” Tam has taken no stand on the current KIUC permits. The matter may come before the Water Commission, and he has not thoroughly reviewed the applications. But he is familiar with FERC from his earlier tenure in the State attorney general’s office.

Between 1989 and 1991, the State opposed FERC jurisdiction over three proposed hydroelectric projects for the upper and lower Wailua River and the Hanalei River. The State objected on the grounds that the projects were not located on “navigable waters,” as provided under the Federal Power Act, and that FERC would assert its authority over in-stream flow standards.

The State Water Code vests that authority to the State Water Commission, which is charged with managing Hawaii’s stream water–a public trust resource–for cultural, ecological and economic purposes. While a California court recognized FERC’s authority to set instream flow standards and another court upheld the State of Washington’s right to set Clean Water Act standards, those questions remain untested in Hawaii, because no FERC hydro project has ever been built in the Islands. However, the issue of FERC jurisdiction has been addressed, at least in part.

On June 2, 1989, FERC ruled that it had no jurisdiction over a proposed “lower Wailua” project–a diversion dam about 1,000 feet upstream from Wailua Falls with a powerhouse about .9 miles upstream of the Fern Grotto–because “the Wailua River has not been shown to be a navigable water at the site of Island Power Co.’s proposed project.” On July 18, 1991, FERC issued an order stating that federal licensing was not required for Island Power’s proposed “upper Wailua” project–again because the site was not on “navigable waters.”

License to Flow

In 1990, however, FERC ruled that it had the authority to issue “voluntary licenses” for a proposed project on the Hanalei River because it constitutes “Commerce Clause waters.” These are defined as “any waterway within the United States…where…water will ultimately end up in public waters such as a river or stream, tributary to a river or stream, lake, reservoir, bay, gulf, sea or ocean either within or adjacent to the United States,” which is true of virtually all streams in Hawaii. Developers ultimately dropped all three projects, leaving unanswered the question of whether federal or state interests prevail. In light of these decade-old orders, Tam said, it is not correct for KIUC to claim that the FERC process is required for the Wailua River. Nor is it accurate to claim that FERC is the only way to secure priority for a project. “The applicant will have to obtain an option or a lease from the landowner at some point,” he said. “Do it up front. No one else will be able to use the property.” Asquith said the KIUC Board could “level the playing field” simply by passing a resolution refusing to buy electricity from any project developed under a FERC permit. KIUC officials say it is too early in the process to sign a lease or obtain an option, because they are uncertain which locations may bear fruit.

Besides, they say, FERC offers the benefit of a clear roadmap for developing hydro, which is lacking at the state level. “It’s a well-defined, transparent process that requires intensive involvement by all stakeholders,” Bissell said. “It gives stakeholders a seat at the table on these important resources people feel very passionate about. It’s really not a way to circumvent the state process.”

KIUC board members also have vowed to secure all the state permits needed for a hydro project. While the FERC process is relatively common in the western United States, Tam does not believe it is appropriate for Hawaii. First, the methodology for determining stream flows on the Mainland is “very different” than what is used in Hawaii, he said. There is also the distance factor. “There just is not a similar ability to participate.

You have to go to Washington to participate in hearings about what is happening in Hawaii streams. We think those kinds of decisions should be made here.” Isaac Moriwake, an Earthjustice attorney who has litigated water use issues on Maui, agrees. “Hawaii has very strong and nationally recognized protections regarding stream flows and Native Hawaiian rights. That stands to be completely wiped out by what KIUC is doing, and it seems they’re doing it for that purpose,” he said.

A Matter of Trust

The (DHHL) raised similar concerns in its intervention request. “Hawaii law grants DHHL priority over other users of the State of Hawaii’s water resources, including water in the East Kauai Irrigation System, which encompasses the Wailua Reservoir. In addition, a preliminary permit would afford [KIUC] certain priorities that may interfere with DHHL’s current and future development of the area’s hydrologic resources.” Asquith was also disturbed by that prospect. “Water in Hawaii is a highly provincial resource, hydrologically, socially, culturally–even the rain has a different name in each valley,” he said. “It is impossible to convey the depth of the value of water to someone who hasn’t taken time to understand it. The FERC bomb was just this horrific breach of protocol that was shocking to me.”

The insensitivity displayed by KIUC and FFP, both of which failed to consult key players before filing permit applications, and the prospect of working through a federal process that he termed “more procedural than substantive” motivated Asquith to mount the petition drive. In addition to forcing a vote on the FFP contract–ballots must be cast by July 8–the petition drive also required KIUC to host a general membership meeting, which was held June 4.

More than 100 people attended. Most expressed concerns, grievances and reservations in testimony that spanned the better part of a day. “I support hydro, but in good conscience, how can I vote yes when I don’t know what it’s going to entail, is all I’m saying,” testified Mark Sueyasu, who identified himself as a west Kauai hunter. Puanani Rogers said the utility should have met with Native Hawaiians before moving forward, prompting Bissell to reply that such consultation “is very high on our priorities.”

“You’ve run off down this road in secret…without having the community on board, and I think that’s the core of your problem,” said Les Brosnan, who noted that in its earlier forays into alternative energy, KIUC “chose weak partners that are still flailing around and have failed to deliver.” Some, however, urged KIUC to move ahead. Among them was Councilwoman JoAnn Yukimura, who said she believes that ending the Free Flow contract “will stop our in-house efforts to develop hydro.”

That spurred others to address Bissell’s desire to “get the discussion out of the FERC process and into hydro,” which apparently prompted the utility to distribute hand-held paper fans that read “hydros” on one side and “yes!” on the other. “KIUC has successfully blurred the reason for this meeting,” said Elaine Dunbar, who helped collect petition signatures. “It’s not about hydro. It’s about secrecy and an improper process.” Criticism about the process spilled over into KIUC’s approach to the upcoming vote, including its preparation of a “voter guide” that focused on hydro, with no reference to the petitioners’ concerns about FERC. Petitioners said it seemed unreasonable that KIUC had written the pro and con arguments. KIUC attorney Proudfoot disagreed.

“The Board voted for [the Free Flow contract]. They are entitled to support it. They are not required to help others who don’t support it with the member’s money. That’s why it’s clearly labeled ‘KIUC voters guide.’” Despite edging petitioners out of that particular process, and acknowledging past failures with consultations, KIUC officials said they are fully committed to carefully considering public concerns as they explore hydroelectric development. “This is a decision that will be made in this community, by this community,” said KIUC director, Jan TenBruggencate. Bissell offered his own exhortations at the meeting.

“I encourage everyone to have trust in KIUC, have trust in your elected board, have trust in me and, most importantly, have trust in yourself. The only way these projects will go forward is through overwhelming community support.”Therein seems to lay the crux of the conflict. “If KIUC cannot conduct a single meeting in a manner which addresses the acknowledged intent of the petition and the clear interest of the people attending, how can they possibly conduct complicated community interactions on hydro?” Asquith questioned, in a widely circulated email. “If they cannot refrain from shameful ballot propaganda that completely distorts the intent of the petition and vote, how can they possibly deliver a balanced presentation on hydro?” Or as Kapaa resident Glenn Mickens noted during a break in the meeting:

“There’s only one reason we’re here. It’s a matter of trust. From the get-go, there’s this underlying mistrust for KIUC.And overcoming that mistrust ultimately may prove more difficult for the utility than successfully developing hydroelectric under any process.

Plenty water but no kokua

With one of the world’s wettest places at its summit, Waialeale receives 424 inches of rain each year. Many of Kauai’s numerous streams derive from the lush hilltop, feeding sugar and pineapple plantations and generating the hydroelectric power that ran the plantations’ mills and camps. McBryde Sugar Co. built a plant on the north shore’s Wainiha River in 1905 that continues to generate about 3.6 megawatts of power for Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, while also serving the needs of Kauai Coffee. Seven smaller systems–five of them privately owned–produce another 5 megawatts for the utility. Together, they account for about 15 percent of the island’s total power generation. While several hydro projects were proposed for the Wailua and Hanalei rivers in recent decades, they were all stalled by environmental concerns, community opposition and funding problems.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment