SUBHEAD: A new CRISPR gene-editing technology doesn't seem to bother our federal food regulator.

By Steve Hoffman on 10 May 2016 for Alternet -

(http://www.alternet.org/food/gmo-mushroom-waved-through-usda-potentially-opening-floodgates-wave-frankenfoods)

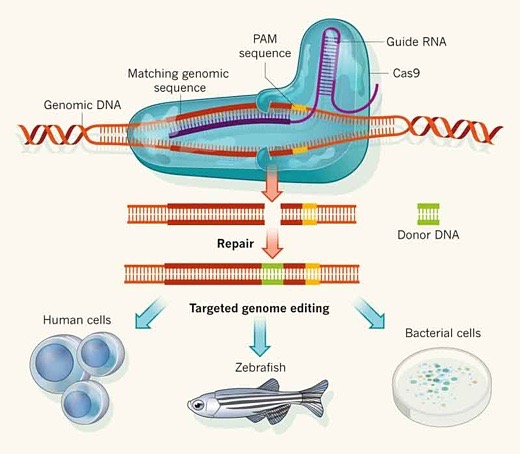

Image above: Diagram of Cas9 and CRISPR gene sequencing technology. From (http://mvresnovae.com/science/witnessing-gene-cutting-in-action/).

Repeat after me: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

That’s CRISPR, a new GE technology that uses an enzyme, Cas9, to cut, edit or remove genes from targeted region of a plant’s DNA. Because it doesn’t involve transgenics, i.e. inserting genes from foreign species into an animal or plant, foods produced in this manner just received a free pass from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to be sold into the marketplace.

In an April 2016 letter to Penn State researcher Yinong Yang, USDA informed the associate professor of plant pathology that his new patent-pending, non-browning mushroom, created via CRISPR technology, would not require USDA approval.

“The notification apparently clears the way for the potential commercial development of the mushroom, which is the first CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited crop deemed to require no regulatory review by USDA,” reported Chuck Gill in Penn State News.

Why does this anti-browning mushroom not require USDA regulation? ”Our genome-edited mushroom has small deletions in a specific gene but contains no foreign DNA integration in its genome," said Yang. "Therefore, we believed that there was no scientifically valid basis to conclude that the CRISPR-edited mushroom is a regulated article based on the definition described in the regulations."

The USDA ruling could open the door for many genetically engineered crops developed using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, said Penn State. In fact, just days after USDA's notification regarding Yang's anti-browning mushroom, the agency announced that a CRISPR-Cas9-edited corn variety developed by DuPont Pioneer also will not be subject to the same USDA regulations as traditional GMOs.

In response to Pioneer's "Regulated Article Letter of Inquiry," about the new GE corn product, the USDA said it does not consider the CRISPR corn "as regulated by USDA Biotechnology Regulatory Services," reported Business Insider.

Not so fast, cautions Michael Hansen, senior scientist for Consumers Union. Just because USDA says CRISPR needs no regulation, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which uses the international CODEX definition of “modern biotechnology,” would “clearly include” the new Penn State CRISPR mushroom, says Hansen.

“The biotechnology industry will be trying to argue to USDA that these newer techniques are more "precise and accurate" than older GE techniques and should require even less, or no scrutiny,” he says. “Thus, the issue of what definition to use for GE is a crucial one,” Hansen points out.

“The government does realize that there is a disconnect between USDA and EPA and FDA about what the definition of genetic engineering is, and that is part of the reason why it is in the process of reviewing the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology,” Hansen says. “Thus, the last sentence in USDA’s letter to Dr. Yang at Penn State would say, ‘Please be advised that your white button mushroom variety described in your letter may still be subject to other regulatory authorities such as FDA or EPA.’”

Yang does plan to submit data about the CRISPR mushroom to the FDA as a precaution before introducing the crop to the market, he says. While FDA clearance is not technically required, Yang told Science News, “We’re not just going to start marketing these mushrooms without FDA approval.”

Gary Ruskin, co-director of the advocacy group U.S. Right to Know, told Fusion on April 25 that the organization’s concerns about genetically engineered food crops extend to Penn State’s new CRISPR mushroom.

“What are the unknowns about CRISPR generally, and in particular, in its application in this mushroom?” he asked. “Regulators should determine whether there are off-target effects. Consumers have the right to know what’s in our food.”

In Europe, however, where anti-GMO advocates have strongly opposed CRISPR, Urs Niggli, director of the Swiss Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) was recently quoted in the German newspaper Taz that CRISPR may be different from traditional GMO technologies and could alleviate some concerns groups like FiBL have with older gene-editing techniques.

His comments have since been subject to much interpretation and criticism among both pro- and anti-GMO circles.

While biotech proponents claim that CRISPR has much to offer, Nature reported in June 2015 that scientists are worried that the field's fast pace leaves little time for addressing ethical and safety concerns. The issue was thrust into the spotlight in April 2015, when news media reported that scientists had used CRISPR technology to engineer human embryos.

The embryos they used were unable to result in a live birth. Nature reported that the news generated heated debate over whether and how CRISPR should be used to make heritable changes to the human genome.

Some scientists want to see more studies that probe whether the technique generates stray and potentially risky genome edits; others worry that edited organisms could disrupt entire ecosystems, Nature reported.

.

By Steve Hoffman on 10 May 2016 for Alternet -

(http://www.alternet.org/food/gmo-mushroom-waved-through-usda-potentially-opening-floodgates-wave-frankenfoods)

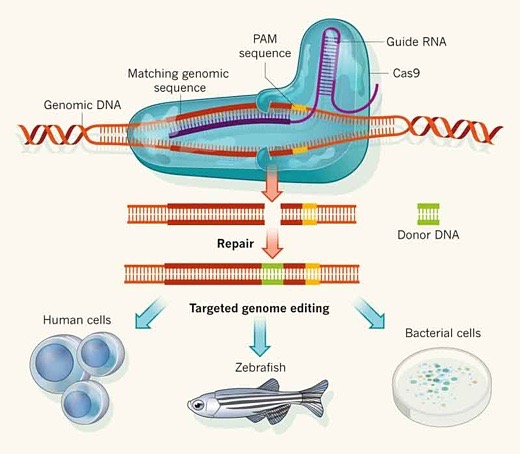

Image above: Diagram of Cas9 and CRISPR gene sequencing technology. From (http://mvresnovae.com/science/witnessing-gene-cutting-in-action/).

Repeat after me: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

That’s CRISPR, a new GE technology that uses an enzyme, Cas9, to cut, edit or remove genes from targeted region of a plant’s DNA. Because it doesn’t involve transgenics, i.e. inserting genes from foreign species into an animal or plant, foods produced in this manner just received a free pass from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to be sold into the marketplace.

In an April 2016 letter to Penn State researcher Yinong Yang, USDA informed the associate professor of plant pathology that his new patent-pending, non-browning mushroom, created via CRISPR technology, would not require USDA approval.

“The notification apparently clears the way for the potential commercial development of the mushroom, which is the first CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited crop deemed to require no regulatory review by USDA,” reported Chuck Gill in Penn State News.

Why does this anti-browning mushroom not require USDA regulation? ”Our genome-edited mushroom has small deletions in a specific gene but contains no foreign DNA integration in its genome," said Yang. "Therefore, we believed that there was no scientifically valid basis to conclude that the CRISPR-edited mushroom is a regulated article based on the definition described in the regulations."

The USDA ruling could open the door for many genetically engineered crops developed using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, said Penn State. In fact, just days after USDA's notification regarding Yang's anti-browning mushroom, the agency announced that a CRISPR-Cas9-edited corn variety developed by DuPont Pioneer also will not be subject to the same USDA regulations as traditional GMOs.

In response to Pioneer's "Regulated Article Letter of Inquiry," about the new GE corn product, the USDA said it does not consider the CRISPR corn "as regulated by USDA Biotechnology Regulatory Services," reported Business Insider.

Not so fast, cautions Michael Hansen, senior scientist for Consumers Union. Just because USDA says CRISPR needs no regulation, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which uses the international CODEX definition of “modern biotechnology,” would “clearly include” the new Penn State CRISPR mushroom, says Hansen.

“The biotechnology industry will be trying to argue to USDA that these newer techniques are more "precise and accurate" than older GE techniques and should require even less, or no scrutiny,” he says. “Thus, the issue of what definition to use for GE is a crucial one,” Hansen points out.

“The government does realize that there is a disconnect between USDA and EPA and FDA about what the definition of genetic engineering is, and that is part of the reason why it is in the process of reviewing the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology,” Hansen says. “Thus, the last sentence in USDA’s letter to Dr. Yang at Penn State would say, ‘Please be advised that your white button mushroom variety described in your letter may still be subject to other regulatory authorities such as FDA or EPA.’”

Yang does plan to submit data about the CRISPR mushroom to the FDA as a precaution before introducing the crop to the market, he says. While FDA clearance is not technically required, Yang told Science News, “We’re not just going to start marketing these mushrooms without FDA approval.”

Gary Ruskin, co-director of the advocacy group U.S. Right to Know, told Fusion on April 25 that the organization’s concerns about genetically engineered food crops extend to Penn State’s new CRISPR mushroom.

“What are the unknowns about CRISPR generally, and in particular, in its application in this mushroom?” he asked. “Regulators should determine whether there are off-target effects. Consumers have the right to know what’s in our food.”

In Europe, however, where anti-GMO advocates have strongly opposed CRISPR, Urs Niggli, director of the Swiss Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) was recently quoted in the German newspaper Taz that CRISPR may be different from traditional GMO technologies and could alleviate some concerns groups like FiBL have with older gene-editing techniques.

His comments have since been subject to much interpretation and criticism among both pro- and anti-GMO circles.

While biotech proponents claim that CRISPR has much to offer, Nature reported in June 2015 that scientists are worried that the field's fast pace leaves little time for addressing ethical and safety concerns. The issue was thrust into the spotlight in April 2015, when news media reported that scientists had used CRISPR technology to engineer human embryos.

The embryos they used were unable to result in a live birth. Nature reported that the news generated heated debate over whether and how CRISPR should be used to make heritable changes to the human genome.

Some scientists want to see more studies that probe whether the technique generates stray and potentially risky genome edits; others worry that edited organisms could disrupt entire ecosystems, Nature reported.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment