SUBHEAD: The art of Phillip Hua displays the contrast between grace and rigidity, between animate life and financial growth.

By Barry Lopez on 1 May 2016 for Orion Magazine -

(https://orionmagazine.org/article/gross-domestic-product/)

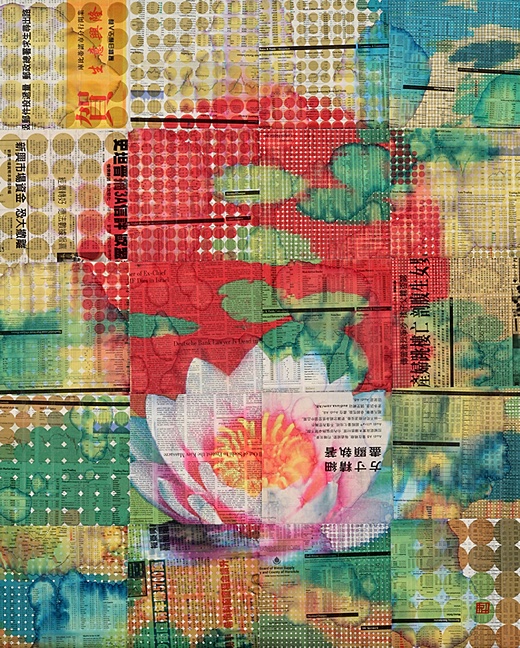

Image above: "What You Own" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

Like a leopard hiding in the limbs of an acacia, Phillip Hua’s artwork caught me by surprise. The contrast between grace and rigidity, between animate life and random, inert news of financial growth, posed for me unbidden questions about wealth, though a mind other than mine could have gone off in some other direction. Hua has layered in a lot of meaning here, in a style reminiscent of classical Chinese painting, which also combines text with image.

I thought first, on seeing these collages, of Sven Beckert, a scholar of the Industrial Revolution, whose Empire of Cotton provides the reader with 250 years of perspective on the situation the West faces today. He begins his analysis by meticulously tracing the origins of industrial capitalism.

The years 1492–1780, writes Beckert, were an era during which the proprietary rights of entrepreneurs, the development of innovative instruments to move capital, state-financed expansion of infrastructure, and the militarized exploration of Europe’s hinterlands prepared the ground from which the Industrial Revolution would spring.

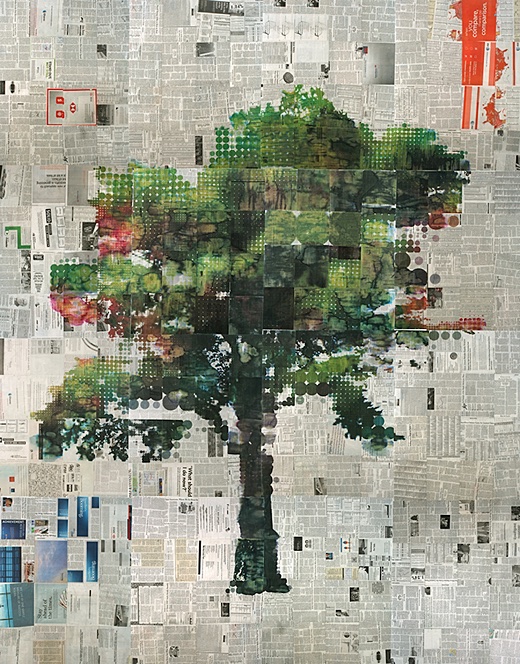

Image above: "Owning the Risk" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

He calls this time “the era of war capitalism” because its most distinctive characteristic was violence—crushing native resistance, expropriating lands, and establishing slavery on a gargantuan scale.

The underlayer of Hua’s collages, a palimpsest beneath the airy layer through which his birds fly, his fish swim, and his trees climb, is the perpetuated record of the violent exploitation Beckert describes. The newspaper graphics seem sinister, in the way a snake ascending a tree toward a clutch of eggs in a nest might seem sinister.

For the moment, Hua’s creatures are able to flit and soar and flourish apart from the implacable lines of regimented information, with all the indifference and volatility they imply.

It’s the very precariousness of the situation, though, that raises for me the question of what we value. Is the promise of material wealth, the rhetoric of buy and sell on these pages, the sort of wealth we hope to secure? Or is the wealth we most desire symbolized by the birds?

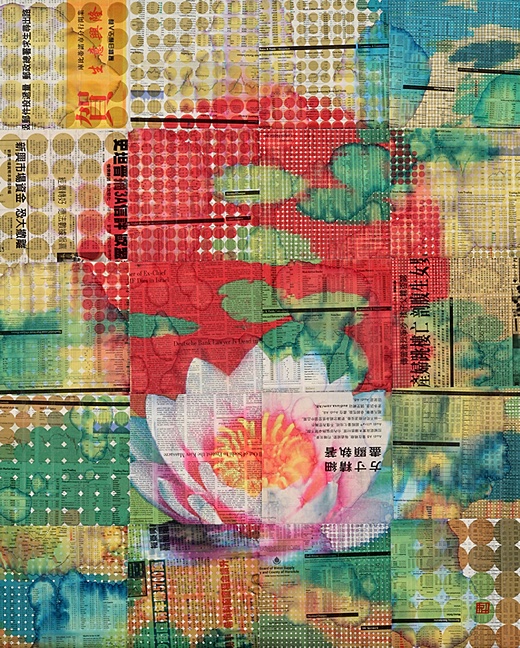

Image above: "Eloquent Indicators" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

Generally speaking, we have enough folklore streaming through our minds about birds—the canary in the mine, the prize goes to the early bird, not a sparrow falls, a life free as a bird’s—to understand at several levels the contrast Hua is creating. His art is not narrowly didactic. It is, instead, ethical and stark, and, importantly, has an international reach.

A shopkeeper in Dhaka or one in Brooklyn knows exactly what’s going on here. Hua’s work follows a line of moral objection that can be traced back at least five hundred years to Bartolomé de las Casas, writing to his Dominican superiors in Spain from the “new world,” in the mid 1500s, denouncing the inhumanity of the encomienda system.

If art is to fulfill its primary purpose, to recollect for us a world other than the one of our daily lives, it must do what Hua has done here—remind us of what we aspire to. His creatures move freely, not yet trapped in the acquisitive, reductive prose beneath them, in which numbers, not lives, often stand for reality.

It would be wrong, I believe, to categorize Hua’s work as political. He is a historian, really, telling us the story we repeatedly forget, the story of unflinching objection to the legacy of war capitalism. His primary aim, I have to think, is not to entertain but to encourage.

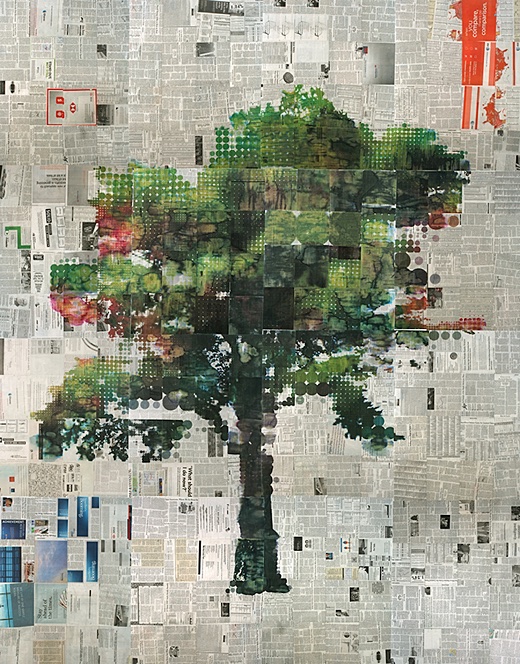

Image above: "Atlas" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

He’s asking whether we wish to continue entrusting our future to strategies for individual profit, to the clamor of bells on the trading floors of stock exchanges, or to the informing sound of birdsong, a sound far more profound than the narrow slot we have provided for birdsong in our cherished texts of natural history.

• Phillip Hua’s art has been widely exhibited, and he has been shortlisted for the Young Masters Art Prize. He teaches at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. Barry Lopez, an Orion contributing editor, is the author of fourteen books, including Arctic Dreams, for which he received the 1986 National Book Award.

.

By Barry Lopez on 1 May 2016 for Orion Magazine -

(https://orionmagazine.org/article/gross-domestic-product/)

Image above: "What You Own" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

Like a leopard hiding in the limbs of an acacia, Phillip Hua’s artwork caught me by surprise. The contrast between grace and rigidity, between animate life and random, inert news of financial growth, posed for me unbidden questions about wealth, though a mind other than mine could have gone off in some other direction. Hua has layered in a lot of meaning here, in a style reminiscent of classical Chinese painting, which also combines text with image.

I thought first, on seeing these collages, of Sven Beckert, a scholar of the Industrial Revolution, whose Empire of Cotton provides the reader with 250 years of perspective on the situation the West faces today. He begins his analysis by meticulously tracing the origins of industrial capitalism.

The years 1492–1780, writes Beckert, were an era during which the proprietary rights of entrepreneurs, the development of innovative instruments to move capital, state-financed expansion of infrastructure, and the militarized exploration of Europe’s hinterlands prepared the ground from which the Industrial Revolution would spring.

Image above: "Owning the Risk" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

He calls this time “the era of war capitalism” because its most distinctive characteristic was violence—crushing native resistance, expropriating lands, and establishing slavery on a gargantuan scale.

The underlayer of Hua’s collages, a palimpsest beneath the airy layer through which his birds fly, his fish swim, and his trees climb, is the perpetuated record of the violent exploitation Beckert describes. The newspaper graphics seem sinister, in the way a snake ascending a tree toward a clutch of eggs in a nest might seem sinister.

For the moment, Hua’s creatures are able to flit and soar and flourish apart from the implacable lines of regimented information, with all the indifference and volatility they imply.

It’s the very precariousness of the situation, though, that raises for me the question of what we value. Is the promise of material wealth, the rhetoric of buy and sell on these pages, the sort of wealth we hope to secure? Or is the wealth we most desire symbolized by the birds?

Image above: "Eloquent Indicators" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

Generally speaking, we have enough folklore streaming through our minds about birds—the canary in the mine, the prize goes to the early bird, not a sparrow falls, a life free as a bird’s—to understand at several levels the contrast Hua is creating. His art is not narrowly didactic. It is, instead, ethical and stark, and, importantly, has an international reach.

A shopkeeper in Dhaka or one in Brooklyn knows exactly what’s going on here. Hua’s work follows a line of moral objection that can be traced back at least five hundred years to Bartolomé de las Casas, writing to his Dominican superiors in Spain from the “new world,” in the mid 1500s, denouncing the inhumanity of the encomienda system.

If art is to fulfill its primary purpose, to recollect for us a world other than the one of our daily lives, it must do what Hua has done here—remind us of what we aspire to. His creatures move freely, not yet trapped in the acquisitive, reductive prose beneath them, in which numbers, not lives, often stand for reality.

It would be wrong, I believe, to categorize Hua’s work as political. He is a historian, really, telling us the story we repeatedly forget, the story of unflinching objection to the legacy of war capitalism. His primary aim, I have to think, is not to entertain but to encourage.

Image above: "Atlas" by Phillip Hua. From original article.

He’s asking whether we wish to continue entrusting our future to strategies for individual profit, to the clamor of bells on the trading floors of stock exchanges, or to the informing sound of birdsong, a sound far more profound than the narrow slot we have provided for birdsong in our cherished texts of natural history.

• Phillip Hua’s art has been widely exhibited, and he has been shortlisted for the Young Masters Art Prize. He teaches at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. Barry Lopez, an Orion contributing editor, is the author of fourteen books, including Arctic Dreams, for which he received the 1986 National Book Award.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment