SUBHEAD: Rootedness can be summarized in a longing to connect with nature, place and people.

By Chris Sunderland on 9 September 2016 for Resilience -

(http://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-08-09/rooted)

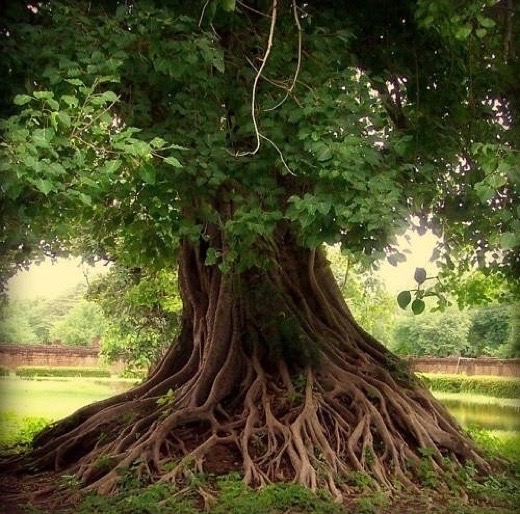

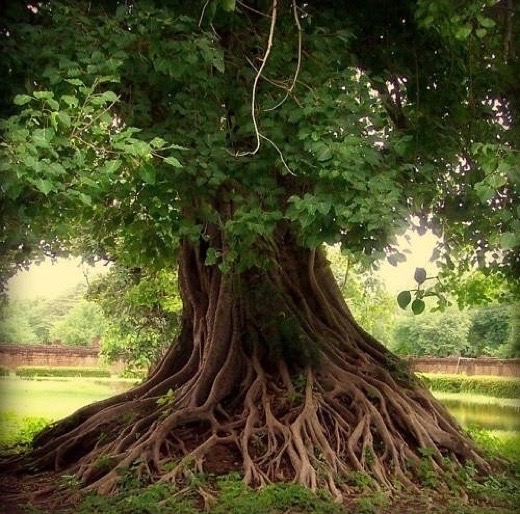

Image above: A magnificent rooted tree. From (https://facetsofcounseling.wordpress.com/2014/03/21/earths-grounding-and-the-roots-of-life/).

With the climate emergency now breaking upon the world, some may wonder whether human society is going to be capable of an effective response. It seems that our current toolkit is threefold.

First there is the political dimension. The Green party is making substantial progress and other parties are lining up their own positions in regard to climate change.

Second are the organizations, like the Transition Movement, where thousands of small scale projects are showing the way to a low energy future.

Third comes the activists, promoting disinvestment away from fossil fuels and opposing fracking. Each of these movements represents a dimension of our response to the ecological crisis with its own distinctive means of approach and each has real success to report, but the scale and urgency of the environmental emergency forces us to ask hard questions.

Are these things enough?

Can we rely on politics to solve this, or is the whole system simply too slow and cumbersome? Why are the activist voices so muted in this age of dread danger?

Can a set of small scale experiments, as witnessed so remarkably in the Transition movement, really shift public perception? Or even, can all these things combined actually do the business and lead us into a better harmony with the earth?

I have come to the opinion that we are set to fail as a human species unless we can embrace one further dimension of our response to the ecological crisis.

And that is the faith dimension. I say ‘faith’ rather than religion, because, in my opinion, the major religions of the world are currently failing in this area. I also use the term ‘faith’ to imply something deeper than a simple strategy for change, something that relates more to our being than our actions and which arises from a deep longing in our hearts.

To introduce my reasoning I would like to take a step back in time.

It is now nearly fifty years since Lynn White published his short paper entitled ‘The historical roots of our ecological crisis’ pointing his finger at the Christian faith for promoting attitudes of earth domination and anthropocentrism and blaming it for our prevailing attitude to the natural world.

It seemed a slightly strange charge to make at the time, because the church of the 1960’s was losing its hold on public consciousness and it was hard to conceive that it could have had such a deep and lasting effect on society.

Yet more recent studies of the human mind show that the structure of our minds changes continually in response to the set of stimuli1 around us. It is clear that through the course of human history we can lose sensitivity to some things and gain sensitivity to others. It is therefore very credible that a religion that attains a public following may nurture one set of moral sympathies while closing down on others and that this may have substantial and lasting impacts on public policy.

This ability to modulate our moral sensitivity may be one of the most important and least recognised properties of faith in society.

White asserted that Christianity was the most anthropocentric religion the world had ever seen. It was a shocking claim addressed, as it was, to members of a society that wanted to believe its historic faith was essentially good, but it raised vital questions.

In Cornwall there are about a hundred natural springs. One of these wells is to be found at, what is now, a National Trust property called Llanhydrock.

Imagine with me, how these springs may have been seen by ancient cultures.

Maybe at first, the fresh water bubbling up from underground reservoirs is perceived by the sensitive imagination as both important and wonderful. The community that grows around the well knows its need of fresh water and senses that the spring’s continual flow is essential to the life of the community.

The people may not document this. They may not even say it. But they know it.

Without this spring their community would not exist. They also may sense the importance of the cleanliness of water. They will have experienced how water from rivers and streams is prone to upstream contamination.

Here is fresh, clean and pure water, flowing continually. The people come each day to collect their water. The place becomes a place of gathering.

The deep sense of importance of this well is known at a subconscious level and finds an outlet in religious imagination, or inspiration. It may feel like a gift. It may feel like its properties need to be guarded, perhaps by a divine being.

So it may have been that a religious imagination gave rise to stories of the well’s origins in order to express such things about its importance to the community that were known at the subconscious level, and as a result, the place came to be invested with religious significance and to become ‘sacred’, meaning set apart, inviolable and a portal to the divine or ‘other’.

Records suggest that the well at Llanhydrock was most likely a pagan shrine in its origins, but was later adopted by the monks of Bodmin and rededicated to the Celtic Saint ‘St ‘ydroch’.

This type of ‘adoption’ of sacred springs was a common practice of the church. It was also an example of anthropocentrism whereby something of mystical value in relation to nature, was replaced by the veneration of a human being.

Such humanisation of the shrine subtly bound the community into the Christian religious fold with its norms and practices.

The Celtic interpretation of the place in due course gave way to Roman Catholic mores and then to the Reformation. Some say that the Protestant Reformation stood for the sweeping away of the sacred itself. Holiness in England, was now to be found in the text, that is the Bible, and in the state, with the King declaring himself head of the Church.

After the dissolution of the monasteries, Llanhydrock was closed as a religious community and became the seat of the Robartes family. They came to own around one third of Cornwall. The well now stands almost forgotten, as little more than a garden feature.

That little vignette of history may give an insight into deep changes in religious sensibility that have taken place in the history of England, and across many of those countries influenced by it.

The reverence for the well at Llanhydroch originated in faith, associated with deep unarticulated values, experience of life ‘beyond words’, and religious sensibility. The shared values, in the case of the well, are as simple as ‘we are the community that need this water’.

The religious sensibility came to inhabit the place by a process of imagination that has been repeated by religions across the world. Such sacred sites did not need to ‘teach’ their sacredness, as an abstract belief system.

Like all authentic religion, it was passed on by imitation. People, who wanted to be in the group, became part of the community and naturally adopted its beliefs. In this sense religion acts like music and values2, in being passed on by an imitative process.

People want to be members of the group. Their pro-social leanings make them want to take on board its understandings of the world. So they embrace the sacredness of the spring and come to ‘believe’ in it.

This anthropomorphic tendency, witnessed by the history of Llanhydroch, has been part and parcel of Judaeo-Christianity from the time of Judaism’s very first struggles with Baal and the Ashtoreth and the need to contend against abhorrent practices like child sacrifice, but anthropocentrism was dramatically accentuated by Christianity’s identification of divinity with a human being.

This has been the genius of Christianity in terms of making the divine feel accessible, but it may also have been its undoing in terms of its relationship with the natural world.3

Anthropocentrism is still very apparent in the church of today, being reinforced by the set services and readings of the church. Week by week the worshipper is presented with a human-focused conception of the world and its challenges.

For example, it is hard to find a single meaningful reference to the natural world in the weekly Anglican liturgy apart from a perfunctory acknowledgement of God who made the world in the creed.

Lynn White further proposed that Christian teaching, arising from the first chapter of Genesis, had led to a widespread attitude in Western Society justifying human domination of the earth.

He referred to the Genesis narrative which tells of the seven days of creation, climaxing in the creation of the human being as ‘the image of God’ and accompanied by the command:

It turns out that there is a strong case that these words were actually important in the rise of science and technology and all that has flowed from that in terms of our relationship to the earth.

They contributed to a scientific mindset, which, even now, continues to be tainted with arrogance towards the earth.

Francis Bacon is acknowledged to be an influential, early scientific visionary and populariser of scientific method. He was one of the first to really grasp the importance of rigorous, wide ranging experiment working in a dynamic relationship with an appropriate theory.

Useful theories would be those that interrogated observations and predicted further experiments. He saw the potential for his method to sweep away so many of the high level and useless theories, or ‘preposterous philosophies’ of his day.

Bacon lived in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when England had been through its church reformation, when Puritanism was in the ascendancy and people were free to imagine new forms of society without some of the constraints of the past.

This was also the age when the Bible was in the foreground of public policy. Dreams of the future were based on biblically justified visions and literal rather than metaphorical readings of the Bible were favoured.

So it was that Francis Bacon dreamt of a future where, through his new method, human beings would ‘conquer’ nature. He talks about science having the ability to ‘to storm and occupy her (nature’s) castles and strongholds and extend the bounds of human empire as far as God Almighty in his goodness shall permit’.5

And his justification for this was a way of reading Genesis, whereby science was helping humankind recover from the frustrations of our existence after ‘the Fall’, restoring us to the original vision of Genesis Chapter One where human beings were magnificently powerful and ruled over all things.6

He described this as the ‘Masculine Birth of Time’ with ‘masculine’ denoting the rationality of this new world as opposed to the supposedly feminine world of feelings.

Bacon may have been a pioneer in scientific development but his imagery about the ideal human relationship to nature is strangely domineering and he justifies it through his interpretation of the Genesis narrative.

His views were popular in his day and would be taken on by nascent scientific bodies like The Royal Society7 as well as colonizers like the New England Company, who wanted to ‘subdue’ and ‘civilise’ their new possessions as quickly as possible.

Since Bacon’s day the role of religion in supporting scientific endeavor has declined, yet it is arguable that that domineering attitude towards nature, established by Bacon, has been passed on to today’s much more secular society so that scientists, engineers and those modern colonizers, the free market fundamentalists, approach the world with an objectivity divorced from any proper fellow feeling that would arise from being participants in the natural order.

In the fifty years that have followed White’s paper, the church has had plenty of time to prove him wrong. Yet, tragically to my mind, it has failed to do so.

We have seen church leaders like Pope Francis and the Archbishop of Canterbury issue strong calls about our responsibilities towards climate change, but the awful truth is these statements do not translate to the grass roots and a dull apathy prevails in most congregations towards environmental concerns.

It is worth noting that Lynn White defined the ecological problem in religious terms. This, in itself, is a contentious thing for many in a secular age. He said:

Changing attitudes can be construed as a religious problem.

With this in mind I will close this essay with some proposals for the recognition of a new spirituality that can act as an antidote to the more poisonous elements of today’s world, like our consumerism, individualism, boredom, destruction of nature and loss of community life. It forges a set of values that allow us to stand against the tide of the free market and create better marks of progress.

I call this inner disposition by the word “Rooted” and it is based on a three-fold longing for connection that I think many people may recognise within themselves.

Firstly, we long to connect again with the natural world. We are searching for ways of life that are in a better harmony with the earth. We believe a new harmony can be found and shape our lives around this search. Some people make substantial sacrifices in this pursuit, doing with little money, exploring radical forms of community living and new enterprise that may shift the dominant patterns of human society.

Secondly, the pursuit of rootedness has to do with the love of a place or places. Reconnecting with the natural world must be expressed in dedicated practice of some kind and this necessarily creates an attachment to particular places.

We care about those places where we have lived and labored. We also care about the great diversity of life in these places that we have observed and come to value and will work to safeguard this.

Thirdly, we value human community life as something precious, which needs to be actively nurtured in our attitudes and practice. We long to go about the world knowing that we belong, as members of a vibrant and inclusive community, recognizing and welcoming the great diversity of humanity as part of the great diversity of the natural world.

So there it is, summarized in a longing to connect with nature, place and people. It is a spirituality for our age that can give shape to our life’s path, helping to form our sense of identity and create our friendships.

It is not a religion, because it has no rules, no membership and no prescribed set of beliefs in the divine.

It is also, for that reason, not a threat to religion and could be embraced by religious and secular people without discrimination.

It could also become a movement, if people chose to make it so. It is the fourth dimension.

This is not a plea for any sort of return to a primitive existence, or a denial of science and technology, or even a denial of city living, which may be the most sustainable way of life for the large numbers of human beings currently on earth, but it is a recognition that we need to find ways of feeling and expressing this sense of being ‘rooted’ within the life of the modern city.

So, we need to discover the natural world, even in this world of cars and tarmac and learn to cherish it with a sacred duty. We need to search for a deeper sense of human community and mutual responsibility for the natural world even within the diverse and creative dynamics of city life.

In my home city of Bristol we have a burgeoning underclass of people who are selfconsciously looking for a new way of life, who prize ‘community’ in a broad and inclusive sense and actively seek harmony with the natural world. These are the ‘rooted’ people. Their spirituality is shaped by their search for a different way of life.

They ‘believe’ another way is possible and are committed to try to live this out. Cities have very similar dynamics all across the world. If we can crack what it means to live as a sustainable city region, we may have the answer to the global problem. And its heart may be in changing our attitude to the world around us.

If we were to place a rediscovery of rootedness at the heart of our modern agenda, we would find a multitude of creative ways of relating to nature and to each other that were deeply enriching to our humanity, while encouraging a way of life in harmony with the earth.

Endnotes

1Susan Greenfield Mind Change Penguin Random House 2014

2Ian McGilchrist The Master and his Emissary Yale University Press 2009

3Chris Sunderland Rise up with wings like eagles Chapter Eight Earth Books, forthcoming publication 2016

4Peter Harrison Subduing the Earth: Genesis 1, Early Modern Science, and the Exploitation of Nature Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Bond University 1999

5Mary Midgely Science and Poetry Routledge 2001 p56ff

6Harrison ibid

7Mary Midgely Science and Poetry Routledge 2001 p 62

Chris' new book, Rise Up with Wings Like Eagles, will be published by Earth Books in December of 2016.

.

By Chris Sunderland on 9 September 2016 for Resilience -

(http://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-08-09/rooted)

Image above: A magnificent rooted tree. From (https://facetsofcounseling.wordpress.com/2014/03/21/earths-grounding-and-the-roots-of-life/).

With the climate emergency now breaking upon the world, some may wonder whether human society is going to be capable of an effective response. It seems that our current toolkit is threefold.

First there is the political dimension. The Green party is making substantial progress and other parties are lining up their own positions in regard to climate change.

Second are the organizations, like the Transition Movement, where thousands of small scale projects are showing the way to a low energy future.

Third comes the activists, promoting disinvestment away from fossil fuels and opposing fracking. Each of these movements represents a dimension of our response to the ecological crisis with its own distinctive means of approach and each has real success to report, but the scale and urgency of the environmental emergency forces us to ask hard questions.

Are these things enough?

Can we rely on politics to solve this, or is the whole system simply too slow and cumbersome? Why are the activist voices so muted in this age of dread danger?

Can a set of small scale experiments, as witnessed so remarkably in the Transition movement, really shift public perception? Or even, can all these things combined actually do the business and lead us into a better harmony with the earth?

I have come to the opinion that we are set to fail as a human species unless we can embrace one further dimension of our response to the ecological crisis.

And that is the faith dimension. I say ‘faith’ rather than religion, because, in my opinion, the major religions of the world are currently failing in this area. I also use the term ‘faith’ to imply something deeper than a simple strategy for change, something that relates more to our being than our actions and which arises from a deep longing in our hearts.

To introduce my reasoning I would like to take a step back in time.

It is now nearly fifty years since Lynn White published his short paper entitled ‘The historical roots of our ecological crisis’ pointing his finger at the Christian faith for promoting attitudes of earth domination and anthropocentrism and blaming it for our prevailing attitude to the natural world.

It seemed a slightly strange charge to make at the time, because the church of the 1960’s was losing its hold on public consciousness and it was hard to conceive that it could have had such a deep and lasting effect on society.

Yet more recent studies of the human mind show that the structure of our minds changes continually in response to the set of stimuli1 around us. It is clear that through the course of human history we can lose sensitivity to some things and gain sensitivity to others. It is therefore very credible that a religion that attains a public following may nurture one set of moral sympathies while closing down on others and that this may have substantial and lasting impacts on public policy.

This ability to modulate our moral sensitivity may be one of the most important and least recognised properties of faith in society.

White asserted that Christianity was the most anthropocentric religion the world had ever seen. It was a shocking claim addressed, as it was, to members of a society that wanted to believe its historic faith was essentially good, but it raised vital questions.

In Cornwall there are about a hundred natural springs. One of these wells is to be found at, what is now, a National Trust property called Llanhydrock.

Imagine with me, how these springs may have been seen by ancient cultures.

Maybe at first, the fresh water bubbling up from underground reservoirs is perceived by the sensitive imagination as both important and wonderful. The community that grows around the well knows its need of fresh water and senses that the spring’s continual flow is essential to the life of the community.

The people may not document this. They may not even say it. But they know it.

Without this spring their community would not exist. They also may sense the importance of the cleanliness of water. They will have experienced how water from rivers and streams is prone to upstream contamination.

Here is fresh, clean and pure water, flowing continually. The people come each day to collect their water. The place becomes a place of gathering.

The deep sense of importance of this well is known at a subconscious level and finds an outlet in religious imagination, or inspiration. It may feel like a gift. It may feel like its properties need to be guarded, perhaps by a divine being.

So it may have been that a religious imagination gave rise to stories of the well’s origins in order to express such things about its importance to the community that were known at the subconscious level, and as a result, the place came to be invested with religious significance and to become ‘sacred’, meaning set apart, inviolable and a portal to the divine or ‘other’.

Records suggest that the well at Llanhydrock was most likely a pagan shrine in its origins, but was later adopted by the monks of Bodmin and rededicated to the Celtic Saint ‘St ‘ydroch’.

This type of ‘adoption’ of sacred springs was a common practice of the church. It was also an example of anthropocentrism whereby something of mystical value in relation to nature, was replaced by the veneration of a human being.

Such humanisation of the shrine subtly bound the community into the Christian religious fold with its norms and practices.

The Celtic interpretation of the place in due course gave way to Roman Catholic mores and then to the Reformation. Some say that the Protestant Reformation stood for the sweeping away of the sacred itself. Holiness in England, was now to be found in the text, that is the Bible, and in the state, with the King declaring himself head of the Church.

After the dissolution of the monasteries, Llanhydrock was closed as a religious community and became the seat of the Robartes family. They came to own around one third of Cornwall. The well now stands almost forgotten, as little more than a garden feature.

That little vignette of history may give an insight into deep changes in religious sensibility that have taken place in the history of England, and across many of those countries influenced by it.

The reverence for the well at Llanhydroch originated in faith, associated with deep unarticulated values, experience of life ‘beyond words’, and religious sensibility. The shared values, in the case of the well, are as simple as ‘we are the community that need this water’.

The religious sensibility came to inhabit the place by a process of imagination that has been repeated by religions across the world. Such sacred sites did not need to ‘teach’ their sacredness, as an abstract belief system.

Like all authentic religion, it was passed on by imitation. People, who wanted to be in the group, became part of the community and naturally adopted its beliefs. In this sense religion acts like music and values2, in being passed on by an imitative process.

People want to be members of the group. Their pro-social leanings make them want to take on board its understandings of the world. So they embrace the sacredness of the spring and come to ‘believe’ in it.

This anthropomorphic tendency, witnessed by the history of Llanhydroch, has been part and parcel of Judaeo-Christianity from the time of Judaism’s very first struggles with Baal and the Ashtoreth and the need to contend against abhorrent practices like child sacrifice, but anthropocentrism was dramatically accentuated by Christianity’s identification of divinity with a human being.

This has been the genius of Christianity in terms of making the divine feel accessible, but it may also have been its undoing in terms of its relationship with the natural world.3

Anthropocentrism is still very apparent in the church of today, being reinforced by the set services and readings of the church. Week by week the worshipper is presented with a human-focused conception of the world and its challenges.

For example, it is hard to find a single meaningful reference to the natural world in the weekly Anglican liturgy apart from a perfunctory acknowledgement of God who made the world in the creed.

Lynn White further proposed that Christian teaching, arising from the first chapter of Genesis, had led to a widespread attitude in Western Society justifying human domination of the earth.

He referred to the Genesis narrative which tells of the seven days of creation, climaxing in the creation of the human being as ‘the image of God’ and accompanied by the command:

‘Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon it’.Subsequent commentators have tried to argue that these words were not meant in their domineering sense but as a more benign ‘stewardship’ over all things, but this is to miss the point. The assessment of White’s critique concerns how these words were received by people at the time, not how they should have been interpreted.4

It turns out that there is a strong case that these words were actually important in the rise of science and technology and all that has flowed from that in terms of our relationship to the earth.

They contributed to a scientific mindset, which, even now, continues to be tainted with arrogance towards the earth.

Francis Bacon is acknowledged to be an influential, early scientific visionary and populariser of scientific method. He was one of the first to really grasp the importance of rigorous, wide ranging experiment working in a dynamic relationship with an appropriate theory.

Useful theories would be those that interrogated observations and predicted further experiments. He saw the potential for his method to sweep away so many of the high level and useless theories, or ‘preposterous philosophies’ of his day.

Bacon lived in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when England had been through its church reformation, when Puritanism was in the ascendancy and people were free to imagine new forms of society without some of the constraints of the past.

This was also the age when the Bible was in the foreground of public policy. Dreams of the future were based on biblically justified visions and literal rather than metaphorical readings of the Bible were favoured.

So it was that Francis Bacon dreamt of a future where, through his new method, human beings would ‘conquer’ nature. He talks about science having the ability to ‘to storm and occupy her (nature’s) castles and strongholds and extend the bounds of human empire as far as God Almighty in his goodness shall permit’.5

And his justification for this was a way of reading Genesis, whereby science was helping humankind recover from the frustrations of our existence after ‘the Fall’, restoring us to the original vision of Genesis Chapter One where human beings were magnificently powerful and ruled over all things.6

He described this as the ‘Masculine Birth of Time’ with ‘masculine’ denoting the rationality of this new world as opposed to the supposedly feminine world of feelings.

Bacon may have been a pioneer in scientific development but his imagery about the ideal human relationship to nature is strangely domineering and he justifies it through his interpretation of the Genesis narrative.

His views were popular in his day and would be taken on by nascent scientific bodies like The Royal Society7 as well as colonizers like the New England Company, who wanted to ‘subdue’ and ‘civilise’ their new possessions as quickly as possible.

Since Bacon’s day the role of religion in supporting scientific endeavor has declined, yet it is arguable that that domineering attitude towards nature, established by Bacon, has been passed on to today’s much more secular society so that scientists, engineers and those modern colonizers, the free market fundamentalists, approach the world with an objectivity divorced from any proper fellow feeling that would arise from being participants in the natural order.

In the fifty years that have followed White’s paper, the church has had plenty of time to prove him wrong. Yet, tragically to my mind, it has failed to do so.

We have seen church leaders like Pope Francis and the Archbishop of Canterbury issue strong calls about our responsibilities towards climate change, but the awful truth is these statements do not translate to the grass roots and a dull apathy prevails in most congregations towards environmental concerns.

It is worth noting that Lynn White defined the ecological problem in religious terms. This, in itself, is a contentious thing for many in a secular age. He said:

‘More science and technology are not going to get us out of the present ecological crisis until we find a new religion, or rethink our old one.’As I understand it, White was not saying there was anything wrong with scientific method per se, but there was something deeply wrong with the attitude towards the natural world that frequently accompanies scientific interventions.

Changing attitudes can be construed as a religious problem.

With this in mind I will close this essay with some proposals for the recognition of a new spirituality that can act as an antidote to the more poisonous elements of today’s world, like our consumerism, individualism, boredom, destruction of nature and loss of community life. It forges a set of values that allow us to stand against the tide of the free market and create better marks of progress.

I call this inner disposition by the word “Rooted” and it is based on a three-fold longing for connection that I think many people may recognise within themselves.

Firstly, we long to connect again with the natural world. We are searching for ways of life that are in a better harmony with the earth. We believe a new harmony can be found and shape our lives around this search. Some people make substantial sacrifices in this pursuit, doing with little money, exploring radical forms of community living and new enterprise that may shift the dominant patterns of human society.

Secondly, the pursuit of rootedness has to do with the love of a place or places. Reconnecting with the natural world must be expressed in dedicated practice of some kind and this necessarily creates an attachment to particular places.

We care about those places where we have lived and labored. We also care about the great diversity of life in these places that we have observed and come to value and will work to safeguard this.

Thirdly, we value human community life as something precious, which needs to be actively nurtured in our attitudes and practice. We long to go about the world knowing that we belong, as members of a vibrant and inclusive community, recognizing and welcoming the great diversity of humanity as part of the great diversity of the natural world.

So there it is, summarized in a longing to connect with nature, place and people. It is a spirituality for our age that can give shape to our life’s path, helping to form our sense of identity and create our friendships.

It is not a religion, because it has no rules, no membership and no prescribed set of beliefs in the divine.

It is also, for that reason, not a threat to religion and could be embraced by religious and secular people without discrimination.

It could also become a movement, if people chose to make it so. It is the fourth dimension.

This is not a plea for any sort of return to a primitive existence, or a denial of science and technology, or even a denial of city living, which may be the most sustainable way of life for the large numbers of human beings currently on earth, but it is a recognition that we need to find ways of feeling and expressing this sense of being ‘rooted’ within the life of the modern city.

So, we need to discover the natural world, even in this world of cars and tarmac and learn to cherish it with a sacred duty. We need to search for a deeper sense of human community and mutual responsibility for the natural world even within the diverse and creative dynamics of city life.

In my home city of Bristol we have a burgeoning underclass of people who are selfconsciously looking for a new way of life, who prize ‘community’ in a broad and inclusive sense and actively seek harmony with the natural world. These are the ‘rooted’ people. Their spirituality is shaped by their search for a different way of life.

They ‘believe’ another way is possible and are committed to try to live this out. Cities have very similar dynamics all across the world. If we can crack what it means to live as a sustainable city region, we may have the answer to the global problem. And its heart may be in changing our attitude to the world around us.

If we were to place a rediscovery of rootedness at the heart of our modern agenda, we would find a multitude of creative ways of relating to nature and to each other that were deeply enriching to our humanity, while encouraging a way of life in harmony with the earth.

Endnotes

1Susan Greenfield Mind Change Penguin Random House 2014

2Ian McGilchrist The Master and his Emissary Yale University Press 2009

3Chris Sunderland Rise up with wings like eagles Chapter Eight Earth Books, forthcoming publication 2016

4Peter Harrison Subduing the Earth: Genesis 1, Early Modern Science, and the Exploitation of Nature Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Bond University 1999

5Mary Midgely Science and Poetry Routledge 2001 p56ff

6Harrison ibid

7Mary Midgely Science and Poetry Routledge 2001 p 62

Chris' new book, Rise Up with Wings Like Eagles, will be published by Earth Books in December of 2016.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment