SUBHEAD: Chevron, Exxon and Shell spent more than $120B in 2013 to boost oil and gas output, but production is down.

By Daniel Gilbert on 28 January 2014 for the Wall Street Journal -

(http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303277704579348332283819314)

Image above: A group that includes Exxon and Shell plans to spend $40 billion to pump oil from man-made islands in the Caspian Sea. The project's budget has ballooned from $10 billion. From original article.

Chevron Corporation, Exxon Corporation and Royal Dutch Shell spent more than $120 billion in 2013 to boost their oil and gas output—about the same cost in today's dollars as putting a man on the moon.

But the three oil giants have little to show for all their big spending. Oil and gas production are down despite combined capital expenses of a half-trillion dollars in the past five years. Each company is expected to report later this week a profit decline for 2013 compared with 2012, even though oil prices are high.

One of the biggest problems: Costs are soaring for many of the new "megaprojects" to tap petroleum deposits needed to replenish depleting fields.

Plans under way to pump oil using man-made islands in the Caspian Sea could cost a consortium that includes Exxon and Shell $40 billion, up from the original budget of $10 billion. The price tag for a natural-gas project in Australia, called Gorgon and jointly owned by the three companies, has ballooned 45% to $54 billion. Shell is spending at least $10 billion on untested technology to build a natural-gas plant on a large boat so the company can tap a remote field, according to people who have worked on the project.

Finding the next gusher has always been a risky business, sending oil companies beneath the ocean floor and into unstable parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Now the pursuit is trickier and more expensive than ever. The easiest-to-reach oil ran dry long ago, and the most prolific fields often are controlled by state-owned companies in places like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

As a result, Chevron, Exxon and Shell are digging even deeper into their pockets, putting their usually reliable profit margins in jeopardy. Exxon is borrowing more, dipping into its cash pile and buying back fewer shares to help the Irving, Texas, company cover capital costs.

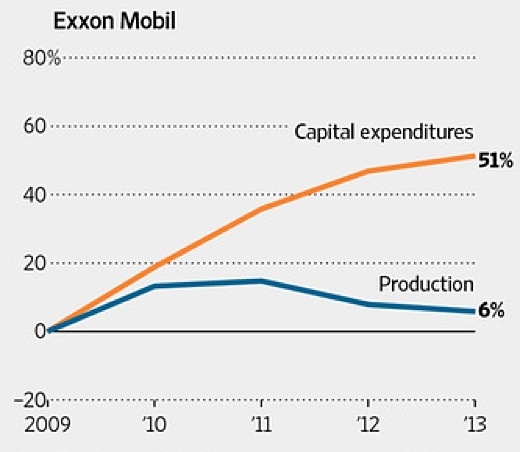

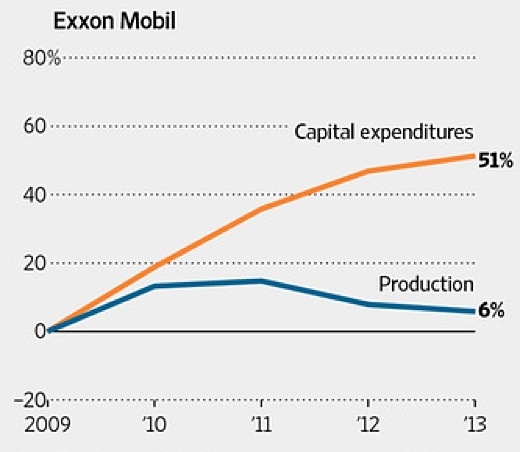

Exxon has said such costs would hit about $41 billion last year, up 51% from $27.1 billion in 2009.

Image above: Chart of Exxon investment dollars and production results. To see Chevron and Shell results click on image. From original article.

As they pursued the big-bet strategy, the three oil giants arrived late to the shale boom in North America, where they missed out on profits raked in by smaller, nimbler companies that pioneered how to extract oil and gas from the dense rock.

The news isn't all bad. Combined profits at Chevron, Exxon and Shell totaled about $70 billion in 2013, according to analysts' estimates. Exxon and Shell report fourth-quarter and full-year results Thursday, while Chevron announces its results Friday. In 2012, the three companies earned nearly $100 billion.

Exxon and Chevron are pressing ahead with their megaprojects, confident they will boost production within three years. "Before we make the first cut with a saw, we re-measure five times instead of one," says Ken Cohen, Exxon's vice president of public and government affairs.

By 2017, Exxon will pump a million new barrels of oil per day and the equivalent in natural gas, showing the company's ability to deliver big projects on time, executives say. Exxon's output started to rebound in late 2013 after a two-year decline, helped by new crude from a $13 billion oil-sands project in Canada. The project's cost rose $2 billion since 2011 because of regulatory hurdles and permit delays.

In a sign of the growing pressure, Shell is reconsidering some investments in "elephant projects" that cost billions of dollars and were a key part of the company's growth strategy. Earlier this month, Shell announced its first profit warning in 10 years and has vowed to focus more on profitability than increasing its oil and gas output.

Full-year earnings at Shell are expected to total about $16.8 billion, down from $27.2 billion in 2012. Net capital spending hit $44.3 billion in 2013, up nearly 50% from 2012.

Oil-industry experts say it will be difficult for the oil giants to spend less because they need to replenish the oil and gas they are pumping—and must keep up with rivals in the world-wide exploration race.

"If you don't spend, you're going to shrink," says Dan Pickering, co-president of Tudor, Pickering Holt & Co., an investment bank in Houston that specializes in the energy industry. Unfortunately for the oil giants, though, "I don't think there's any way these projects are more profitable than their legacy production," he adds.

Chevron has been especially aggressive, promising a 25% increase in oil and gas output by 2017. Last year, the San Ramon, Calif., company poured $42 billion into oil and gas projects, more than double its 2010 total, even though Chevron is half as big as Exxon or Shell by annual revenue. Chevron plans to spend an additional $40 billion in 2014.

The spending surge has drawn attention from U.S. securities regulators, who have demanded more disclosure from Chevron about whether the jump will get even bigger and affect the company's liquidity. Chevron told regulators it will provide more details.

Chevron's most gargantuan projects, from Australia to the Gulf of Mexico, haven't generated any cash flow yet—and might not until next year. The lag between the upfront investment in the projects and their output is pressuring Chevron's bottom line. Analysts expect the company to report that profits fell about 20% to $21 billion in 2013 from $26.2 billion in 2012.

The Gorgon natural-gas project is one of the most extreme examples of the runaway costs that haunt Chevron, Exxon and Shell. The three companies teamed up in 2009 to build the plant on an island reserve 40 miles off Australia's coast, aiming to tap a natural-gas trove estimated at 40 trillion cubic feet. Gorgon could be productive for decades and feed energy-hungry Japan, South Korea and China.

Chevron staked more than $18 billion of its own money on Gorgon, one of the company's biggest projects ever, owns nearly half of the project and runs it. Exxon and Shell own a 25% stake each.

Gorgon, also the name of sisters in Greek mythology who had snakes in their hair and could turn beholders to stone, presents unusually tough challenges. The gas produced there must be piped 80 miles across a mountainous sea floor to Barrow Island, home to so many unusual species of plants and animals that locals call it "Australia's Ark."

Then the natural gas has to be purified and run through giant chillers that condense it into liquid form so it can be shipped on tankers.

Barrow Island's sensitive ecology meant that much of Gorgon's construction had to be done elsewhere, with hundreds of thousands of tons of buildings and equipment disinfected and shrink-wrapped to keep out invasive species.

Chevron executives brushed aside analysts' worries about the project's cost. "We see a window of opportunity to move forward with Gorgon, timing it to capture growing market demand while benefiting from a lowering cost environment," George Kirkland, now Chevron's vice chairman, said in March 2009.

Costs soon spiked higher. Labor costs rose because of fierce competition for skilled workers as other companies committed to spending more than $100 billion in similar gas projects across Australia. The strong Australian dollar inflated the cost of materials. Cyclones slowed work on Gorgon and forced Chevron, Exxon and Shell to build stormproof camps for workers.

Gorgon was about half-finished in December 2012 when Chevron estimated the project would cost a total of $52 billion—or 40% over budget. Last month, Chevron tacked an additional $2 billion to the price tag. The project now is 75% complete, according to the company.

"The economics of the Gorgon project are strong," says Kurt Glaubitz, a Chevron spokesman. The company has struck deals to sell most of Gorgon's output under contracts tied to oil prices that are up about 60% since Chevron committed itself to the project, he adds.

Chevron says it is working hard to keep costs in line. A civil-engineering unit dedicated to managing expenses and overseeing contractors has tripled to 120 employees since 2008. The company has about 62,000 employees.

Gary Fischer, who leads the unit and started at Chevron as an intern in 1979, said at an industry conference in November that the company has intensified its focus on completing megaprojects on time and on budget. Those projects "are very fragile," he said, "and they're totally unforgiving."

See also:

New Shell CEO Ben van Beurden "I am not prepared to commit further resources for drilling in Alaska in 2014" (http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/media/news-and-media-releases/2014/2014-results-announcement-media-release1.html)

.

By Daniel Gilbert on 28 January 2014 for the Wall Street Journal -

(http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303277704579348332283819314)

Image above: A group that includes Exxon and Shell plans to spend $40 billion to pump oil from man-made islands in the Caspian Sea. The project's budget has ballooned from $10 billion. From original article.

Chevron Corporation, Exxon Corporation and Royal Dutch Shell spent more than $120 billion in 2013 to boost their oil and gas output—about the same cost in today's dollars as putting a man on the moon.

But the three oil giants have little to show for all their big spending. Oil and gas production are down despite combined capital expenses of a half-trillion dollars in the past five years. Each company is expected to report later this week a profit decline for 2013 compared with 2012, even though oil prices are high.

One of the biggest problems: Costs are soaring for many of the new "megaprojects" to tap petroleum deposits needed to replenish depleting fields.

Plans under way to pump oil using man-made islands in the Caspian Sea could cost a consortium that includes Exxon and Shell $40 billion, up from the original budget of $10 billion. The price tag for a natural-gas project in Australia, called Gorgon and jointly owned by the three companies, has ballooned 45% to $54 billion. Shell is spending at least $10 billion on untested technology to build a natural-gas plant on a large boat so the company can tap a remote field, according to people who have worked on the project.

Finding the next gusher has always been a risky business, sending oil companies beneath the ocean floor and into unstable parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Now the pursuit is trickier and more expensive than ever. The easiest-to-reach oil ran dry long ago, and the most prolific fields often are controlled by state-owned companies in places like Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

As a result, Chevron, Exxon and Shell are digging even deeper into their pockets, putting their usually reliable profit margins in jeopardy. Exxon is borrowing more, dipping into its cash pile and buying back fewer shares to help the Irving, Texas, company cover capital costs.

Exxon has said such costs would hit about $41 billion last year, up 51% from $27.1 billion in 2009.

Image above: Chart of Exxon investment dollars and production results. To see Chevron and Shell results click on image. From original article.

As they pursued the big-bet strategy, the three oil giants arrived late to the shale boom in North America, where they missed out on profits raked in by smaller, nimbler companies that pioneered how to extract oil and gas from the dense rock.

The news isn't all bad. Combined profits at Chevron, Exxon and Shell totaled about $70 billion in 2013, according to analysts' estimates. Exxon and Shell report fourth-quarter and full-year results Thursday, while Chevron announces its results Friday. In 2012, the three companies earned nearly $100 billion.

Exxon and Chevron are pressing ahead with their megaprojects, confident they will boost production within three years. "Before we make the first cut with a saw, we re-measure five times instead of one," says Ken Cohen, Exxon's vice president of public and government affairs.

By 2017, Exxon will pump a million new barrels of oil per day and the equivalent in natural gas, showing the company's ability to deliver big projects on time, executives say. Exxon's output started to rebound in late 2013 after a two-year decline, helped by new crude from a $13 billion oil-sands project in Canada. The project's cost rose $2 billion since 2011 because of regulatory hurdles and permit delays.

In a sign of the growing pressure, Shell is reconsidering some investments in "elephant projects" that cost billions of dollars and were a key part of the company's growth strategy. Earlier this month, Shell announced its first profit warning in 10 years and has vowed to focus more on profitability than increasing its oil and gas output.

Full-year earnings at Shell are expected to total about $16.8 billion, down from $27.2 billion in 2012. Net capital spending hit $44.3 billion in 2013, up nearly 50% from 2012.

Oil-industry experts say it will be difficult for the oil giants to spend less because they need to replenish the oil and gas they are pumping—and must keep up with rivals in the world-wide exploration race.

"If you don't spend, you're going to shrink," says Dan Pickering, co-president of Tudor, Pickering Holt & Co., an investment bank in Houston that specializes in the energy industry. Unfortunately for the oil giants, though, "I don't think there's any way these projects are more profitable than their legacy production," he adds.

Chevron has been especially aggressive, promising a 25% increase in oil and gas output by 2017. Last year, the San Ramon, Calif., company poured $42 billion into oil and gas projects, more than double its 2010 total, even though Chevron is half as big as Exxon or Shell by annual revenue. Chevron plans to spend an additional $40 billion in 2014.

The spending surge has drawn attention from U.S. securities regulators, who have demanded more disclosure from Chevron about whether the jump will get even bigger and affect the company's liquidity. Chevron told regulators it will provide more details.

Chevron's most gargantuan projects, from Australia to the Gulf of Mexico, haven't generated any cash flow yet—and might not until next year. The lag between the upfront investment in the projects and their output is pressuring Chevron's bottom line. Analysts expect the company to report that profits fell about 20% to $21 billion in 2013 from $26.2 billion in 2012.

The Gorgon natural-gas project is one of the most extreme examples of the runaway costs that haunt Chevron, Exxon and Shell. The three companies teamed up in 2009 to build the plant on an island reserve 40 miles off Australia's coast, aiming to tap a natural-gas trove estimated at 40 trillion cubic feet. Gorgon could be productive for decades and feed energy-hungry Japan, South Korea and China.

Chevron staked more than $18 billion of its own money on Gorgon, one of the company's biggest projects ever, owns nearly half of the project and runs it. Exxon and Shell own a 25% stake each.

Gorgon, also the name of sisters in Greek mythology who had snakes in their hair and could turn beholders to stone, presents unusually tough challenges. The gas produced there must be piped 80 miles across a mountainous sea floor to Barrow Island, home to so many unusual species of plants and animals that locals call it "Australia's Ark."

Then the natural gas has to be purified and run through giant chillers that condense it into liquid form so it can be shipped on tankers.

Barrow Island's sensitive ecology meant that much of Gorgon's construction had to be done elsewhere, with hundreds of thousands of tons of buildings and equipment disinfected and shrink-wrapped to keep out invasive species.

Chevron executives brushed aside analysts' worries about the project's cost. "We see a window of opportunity to move forward with Gorgon, timing it to capture growing market demand while benefiting from a lowering cost environment," George Kirkland, now Chevron's vice chairman, said in March 2009.

Costs soon spiked higher. Labor costs rose because of fierce competition for skilled workers as other companies committed to spending more than $100 billion in similar gas projects across Australia. The strong Australian dollar inflated the cost of materials. Cyclones slowed work on Gorgon and forced Chevron, Exxon and Shell to build stormproof camps for workers.

Gorgon was about half-finished in December 2012 when Chevron estimated the project would cost a total of $52 billion—or 40% over budget. Last month, Chevron tacked an additional $2 billion to the price tag. The project now is 75% complete, according to the company.

"The economics of the Gorgon project are strong," says Kurt Glaubitz, a Chevron spokesman. The company has struck deals to sell most of Gorgon's output under contracts tied to oil prices that are up about 60% since Chevron committed itself to the project, he adds.

Chevron says it is working hard to keep costs in line. A civil-engineering unit dedicated to managing expenses and overseeing contractors has tripled to 120 employees since 2008. The company has about 62,000 employees.

Gary Fischer, who leads the unit and started at Chevron as an intern in 1979, said at an industry conference in November that the company has intensified its focus on completing megaprojects on time and on budget. Those projects "are very fragile," he said, "and they're totally unforgiving."

See also:

New Shell CEO Ben van Beurden "I am not prepared to commit further resources for drilling in Alaska in 2014" (http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/media/news-and-media-releases/2014/2014-results-announcement-media-release1.html)

.

No comments :

Post a Comment