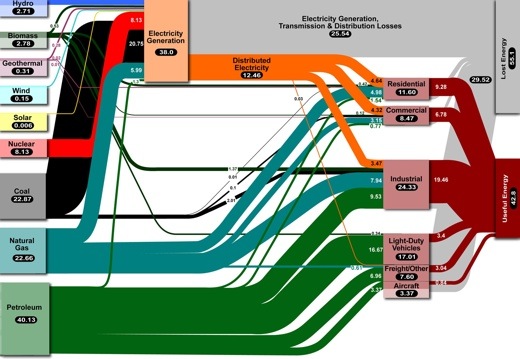

Image above: Detail of energy flow chart for US economy. Click to enlarge. From (http://www.schizoidboy.com/wasted-energy.html).

By George Mobus on 15 November 2010 in Question Everything -

(http://questioneverything.typepad.com/question_everything/2010/11/the-economy-is-energy.html)

Image above: Detail of energy flow chart for US economy. Click to enlarge. From (http://www.schizoidboy.com/wasted-energy.html).

By George Mobus on 15 November 2010 in Question Everything -

(http://questioneverything.typepad.com/question_everything/2010/11/the-economy-is-energy.html)

And why do American manufacturing and some service industries move off-shore?

The answer to both of these questions is ridiculously simple. Americans, and to a little lesser degree all of the developed world workers, require a huge amount of energy to live. Chinese workers have lived lifestyles that use far less energy. The same applies to the Indian workers.

This won't remain so for much longer. In fact it is already starting to shift in China where the workers, as consumers, are starting to demand higher wages so that they can also live the ‘good life’. They want stuff and services like the developed countries have supplied to their people. And all of that stuff and services take more energy to produce.

Everything is About Energy FlowThis may seem like a rash claim. It is certainly not what comes to mind when we think about our lives and our economic activities. Yet it is a simple law of nature that all activity is some form of physical work, even mental activity is biochemical work. And all work takes energy to accomplish. If you think this is overplayed try stopping eating for a while and see if the economy of your body can last very long without calories.

Work can come in the form of moving things, reshaping things, extracting resources from nature, putting things together, etc. It can be accomplished by human labor or machine labor (with control labor supplied by humans). In all cases, regardless of what materials are involved, the one common, absolutely necessary, element is energy.

We human beings are at the center of a vast network of material and high power energy flows. We are the ultimate users of all energy flows that we control. Everything we do by way of economic work is designed to support our lives. In the developed world this support comes in the form of making our lives easier so that we don't have to do as much physical work to meet our needs and wants. This is a slightly different perspective on a subject that I've written about before (“Our Energy Cocoon”). I thought this graphic might make it clearer how each of us, and particularly our family units are at the center of this web of energy flows.

Everything that we use or consume directly comes from work processes in the general economy that also consume energy in producing what they make. And today, most of that energy comes from fossil fuels, more than 80% in the US (the other 20% coming mostly from hydroelectric dams and nuclear power plants with a very small contributions from wind and solar).

Start with the absolutely most fundamental things that keep you and your family alive — food. Unless you are involved in some form of agricultural activity (raising your own veggies?) you more than likely do what most people do and buy your food stuffs at a grocery store. The grocery store requires quite a lot of energy, mostly electricity, to operate, especially those freezers that keep prepackaged foods viable. The foods generally come from far away and require a fair amount of liquid fuels for transportation. Most of them were prepared and packaged at a processing plant and sent in bulk to distributors. All of that work required energy. And then, of course there is the energy needed to grow the food in the first place, on industrial-sized mega farms. I'm not talking about the sunlight, I'm talking about the fossil fuels needed to run the farm equipment. I'm talking about the energy needed to maintain the farmhouse and occupants (more on this in a bit).

Solar energy is, in a sense, free. Crops do a wonderful job of converting sunlight into chemical energy packets that our bodies can use to keep us alive. But crops don't plant and harvest themselves! Modern industrial-scale agriculture depends on a lot of heavy equipment that uses fossil fuels at a prodigious rate. It also depends on inputs of artificial fertilizers (made from natural gas) and pesticides (derived from petroleum) as well as irrigation made possible by very large electric pumps.

By the time you add up all of the calories of fossil fuels needed to put one calorie of food onto your plate you get something like 9 to 10, not counting the solar energy that the plants absorbed but didn't get into the food products. If you added that in (like the calories stored in the non-edible parts of the plants and animals) you are looking at something like 1,000 calories of sunlight needed for every calorie of food you eat. Not terribly efficient considering that hunter-gatherers' supply chain needed maybe one tenth of that to get one calorie.

But this just considers the obvious, direct energy needed to put food on your table. There is also the energy that is consumed by every worker in the supply chain. Each worker has energy requirements for him or herself and their families. They too want to live lifestyles comparable with their ultimate customers. When a farm worker looks for an income, it is based on getting food and basics as well as some amenities for his/her family.

Workers and ConsumersFamilies need clothing, shelter (a home), and various other services such as transportation as well as food. Each of these needs can be seen as having origins in production processes that consume energy producing the products and services involved. Around the circle of direct use are myriad other processes that are composed of machines consuming energy and humans who want to consume energy in the form of the things those other processes produce. Every worker directs the consumption of energy in production at their job, but also consumes the energy used in all of the other productions surrounding them and their families. Each person is at the nexus of an incredibly complex web of energy flows.

It actually started out quite simply in times gone by. An excellent hunter provided some of his kill to the excellent arrow maker. They both got sufficient energy for their biological units (the family) by both specializing and using their combined skills to efficiently supply meat. But it was always about the flow of energy to keep the biology working. Both worked and both consumed. It was all quite natural.

Over time the specializations increased as the needs for managing energy flow increased. The advent of agriculture required very elaborate management systems. The need to protect settled land invoked even more complexity in the form of professional warriors. And the rest, as we say, was history.

Since sooner or later all things manufactured deteriorate to scrap, in a sense everything that humans produce is eventually consumed. We do a pretty poor job of recycling the scrap, though we have gotten a bit better over the last several decades. We are still far from nature's examples of recycling, which is everything eventually gets recycled. Recycling, however, also takes energy.

In nature the Sun provides most of that energy with gravitation and deep nuclear decay in the Earth interior providing more (recycling minerals through volcanos, etc.) Carbon, water, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and many other elements/molecules participate in elaborate solar-driven (but slow) cycles from one source to a sink that later becomes a source. Living ecosystems participate in these and many cycles (e.g. organic carbon in soils). Nothing is wasted in nature. Nothing is lost forever. Mankind has not quite figured out that cycling needs to be the pattern of use for material natural resources.

The one resource that cannot be recycled is energy. It can be stored such as when ancient solar energy got stored as fossil fuels. But once energy is used to do work, it is gone forever. That is it is gone so far as doing any additional work is concerned. All energy is subject to what is known as the first law of thermodynamics which says that energy is neither created nor destroyed. But the second law says that with every conversion of energy (for example in doing work) some portion of that energy is lost in the form of non-recoverable waste heat. Eventually in any work chain all of the input energy is converted to heat, so energy is on a one-way trip through the economy over time. We can store tiny amounts of it for a time, to do some amount of work a little later, as when we charge a battery, but in the long run it all gets used up.

So this is the basic problem. As consumers we are using up stuff that eventually degrades and would need additional energy to repair or recycle. When we work to produce new stuff we are consuming energy for that production. We simply can't get away from the fact that we are always using energy up in everything we do.

Why Things Cost More Over TimeOne thing we've learned from classical economics is that there are rarely super abundances of extracted resources. And from population studies we know that there are generally excesses of human beings being produced as long as the food supply is up to the job. Modern agriculture, especially after the Green Revolution shares some similarities with Moore's Law as applies to digital microelectronics.

With the advent of an abundance of power afforded by the use of fossil fuels, especially oil, agriculture became increasingly capable of supplying abundant food while reducing the number of people required in farming (of course the migrant farm worker population, many illegal aliens in the US, didn't hurt either). In classical economic terms the units of output given the units of labor input is called the productivity.

It is not, however, the same as physical (thermodynamic) efficiency. What was happening is that cheap fuel was increasingly substituted for human labor (through increasingly capable machines) which hid from view what was really going on. In fact more actual energy was being consumed for each calorie of output. But because labor costs were going down economists were left with their own definitional illusion that “efficiency” (the non-thermodynamic kind) was increasing. Everyone was happy.

But how is it that farming costs could be driven down so effectively? And why did the costs of transportation, as well as many other costs go down per unit of output? Why did the gross domestic product increase over time, giving the impression that things might be cheaper to buy?

The answer is the early ease with which high powered fuels could be extracted coupled with the advent and development of efficient machines that could use those fuels to produce the work that had previously been done by human beings. In the early days (late 1800s and early 1900s), for example, it took only about 1 barrel of oil (in equivalent energy units) to extract 100 barrels, giving a net return of 99 barrels to be used for non-energy extraction purposes; in other words the economy.

But over time, as the easy to get oil was extracted, the amount of energy required to get the same 100 barrels started to rise. It got progressively harder to find new oil deposits and they were found in increasingly difficult situations (e.g. off shore, Arctic circle, etc.) that required substantially greater energy investments in equipment as well as higher energy costs in labor and machine work to get the stuff out of the ground.

Today, on average, it takes something like 25 to 30 barrels to extract 100 barrels, or a net return to the economy of 70 to 75 barrels. That may still sound like a lot, but you need to look at the variances between older fields that are still providing relatively cheap production vs. the newer, exotic extraction processes. And you need to look at the dynamics of extraction in these various forms. For example some Saudi Arabian oil is still coming out of the ground at nearly the 75:1 cost but these fields are in declining production — they are running low!

As a result, over time the ratio of return on investment has been steadily declining. But the really dramatic costly extraction is from the newest sources such as shale oil and tar sands. Here the extractions take so much additional energy that the net return is closer to 10 barrels for every 100 extracted! [Note that a lot of work is going into how to best account for the energy return on energy investment and there is still no general consensus on what counts in the cost side. I am basing these numbers generally on the work by some of the experts in this field that I had the pleasure to work with directly. Even if they are not accurate, the magnitude and direction of change are telling enough to be worried.]

Food production got its major boost right at the sweet spot in energy extraction and energy uses in machines to replace human labor. But it couldn't last.

As the net energy return on energy investments (ERoEI) has gone down over the last fifty years or so, the true cost of energy has risen. I say the true cost meaning the cost in terms of energy needed to do the work of extraction as well as conversion to human-usable forms like electricity and liquid fuels for the machines. The dollar costs of fuels and materials is not a good guide to these true costs because dollar values float and are horribly manipulated by the financial system that creates money out of nothing (debt and various forms of appreciation). But most people gauge value in dollar terms because once, not that long ago, the dollar actually had a fixed value based on a weight of gold, a hard asset.

Tying the dollar to a physical measure actually worked pretty well, but there was no real intrinsic value in gold. Its perceived value too came from historical factors (its rarity, value as ornamentation, and later as coins and the economic theories of, e.g. mercantilism) and had no basis in what really mattered to people. You could not, in the end, eat gold. Nor can you eat dollars. You can't build a shelter out of gold or dollars. The truth is that money can only represent one thing in this physical world and that is the amount of energy that is available to do useful work (or the energy that was used to do useful work, called energy memory, also embodied energy, or emergy for short).

You, as a worker (producer), are paid a wage for your labor (energy you expend and control in production). Presumably, either because of skill or smarts, the more production you accomplish per the amounts of energy you use, you are paid more than others. You are not, generally, paid because you are such a sweet person.

As a consumer you pay for things and services, meaning you are paying for work already done or about to be done by other people. You are paying for the way in which energy was used and for the amount of energy used (in toto) to produce the results. You are paying for energy usage based upon your skill at using energy in your job. In other words, money is just a means of sending signals through the economy to guide how energy flows are to be managed and used. That is all it ever was, whether gold coin or paper currency backed by a government's promises. Each unit of money is simply a message about the use of energy in the economy.

The problem is that the way governments get into power, at least in the West and North (and this now includes China!), is by making promises they really can't keep. There is no such thing as infinite growth, especially when it comes to fossil fuel extraction. Yet the promise of a better life for all citizens depends crucially on such growth. This is especially the case when the population of citizens is constantly growing. So governments are deeply motivated to practice legerdemain when it comes to the purchasing power of their currencies.

For the past fifty years we have seemingly enjoyed what appeared to be an increase in purchasing power of the American dollar. First by a real increase supported by expansion of energy sources to do real work, but later by slight of hands by governments in cahoots with banks. The middle class grew and bought lots of stuff. It was supported by increasing incomes up until sometime in the 1970s when it became clear to most households that aspired to the American Dream that it would take two incomes to support the lifestyle desired for the average American middle class family. In spite of the government statistics used to show how wealthy Americans were, the ground truth was that most things were becoming more expensive.

Inflation has haunted the American economy for many decades and most American workers got used to the notion that they could demand, and were owed, a cost of living increase in their wages. Remarkably, given the supposed intelligence of the average American worker, it never occurred to anyone that increasing labor wages contributed to inflation itself. We were caught on a spiral staircase. Increasing labor costs (in dollars but not in energy) because of cost-of-living increases, simply contributed eventually to the cost of products. Then prices moved upward and forced people to think that they needed additional cost-of-living increases to keep up with inflation. What a comical predicament!

Meanwhile, while everyone in politics and economics were focusing on the dollar values of goods and services, no one but a few intrepid critical thinkers were looking at the costs of things in terms of energy. Those were on the rise because of several factors. Energy was increasingly more expensive in energy terms, as argued above. But also, technology, that great mystical power that kept seeming to deliver cheaper goods to us (most made from oil-based plastics!!!) was slowing down. In the arena of digital electronics we were still making strides because of Moore's Law bringing down the energy per bit cost making it possible to manufacture cell phones and give them away in order to capture the service prices of communications and mindless applications.

The same applied to computers, so that the digital revolution looked like a real model of classical economics. There was just one hitch. It only applied to digital electronics, and then only if you had a blind eye to the environmental costs that were accruing due to the way microelectronics were made. All other machines are subject only to the laws of thermodynamics writ large. And in that arena we were already approaching the technological limits of efficiency.

What we had not realized, however, is that a huge and growing amount of our energy uses were really extremely wasteful. We opted for urban sprawl when energy was abundant and cheap. We started a pattern of lifestyle that used up energy in a wasteful way. Everybody wanted a piece of the countryside to call their own and automobiles (with cheap gasoline) made it possible. So why not? We wanted more gadgets and extravagant sports and entertainment events to amuse us. After all, we had so many energy slaves working for us (doing laundry, cooking food, or just buying it already cooked and ready to eat) that we had lots of spare time to waste away on trivialities. Or so we thought.

All the while, the government inflating the sense of wealth of the citizens (who then felt compelled to borrow money to pay for more stuff), the citizens sucking it up as the status quo because it felt good, the basis of all this great feeling was being sucked out of the ground at a rate that could never be sustained. And then, all of a sudden, we reached the slow down in the rate of oil extraction, and now even the peak of extraction rate. And it all has started to crumble beneath our feet.

The Effects of a High Energy LifestyleLook at the carpenters working on the house in the figure above. Each one has a family (on average!) and those families need to eat, have their own house, their own transportation, their own clothes, and their own access to entertainments. Indeed, for every worker involved in every one of the production processes surrounding our center family, construct another circle with its periphery of production processes. As I said above, we are all at the center of our own nexus of the complex web.

Energy costs. It costs in energy needed to supply energy. And it costs in dollars needed to consume energy used. And then the simple fact that the vast majority of the energy we consume comes from non-renewable sources hits home.

Who can actually blame American companies for seeking to cut costs by moving their manufacturing processes off-shore where labor costs are (for the time being) lower. They are lower because those workers consume less energy in their own nexi. They put fewer demands on the energy flows for the time being. Thus, energy costs can be isolated to machine production which is relatively efficient and away from labor. But it will only last for a while.

American (and generally OECD) workers demand lifestyles that are inherently energy intensive. And because energy is the true currency of the economy, they are too expensive for companies to support. Globalization is a completely rational response by international corporations to reduce costs. Produce goods where the labor costs are less and use cheap transportation fuel (bunker oil) to move the products to their respective markets.

The problem is that by forgetting that the consumers of those products, the people who can pay for them, are also in need of productive jobs in order to earn wages to pay for them, those rational managers have destroyed the basis for consumption in the US. Soon, the markets for cheap Chinese-made goods will dry up because the consumers are also the former producers who earned energy credits by virtue of their work.

This is the classic double bind, a no-win scenario. As long as consumers demand the ability to consume energy and energy supply is in decline there is no way to balance the books. Americans and most developed country's citizens feel entitled to a level of consumption that is the historical accident of finding cheap, and previously abundant fossil fuel energy.

They will very likely continue to demand their “rights” to consume even as the supply of energy starts to diminish. They are spoiled. And like all spoiled children can be expected to have temper tantrums when the realities of constraints dawns. Look at the reactions of the populaces in Greece, France, and now England, as austerity measures are enacted. Expect the same thing in the US as conservatives push for expenditure reductions to quell the growing national debt. No one is immune from this fact. The decline of energy available to do real work means we are all going to get a whole lot poorer over the next few decades.

But we need to recognize that this version of being poorer is based on the idea that increasing consumption is what we mean by being richer. This is a fundamental fallacy that has been promoted and promulgated by many neoclassical economists and all politicians. They are fundamentally wrong.

We are not richer by wasting energy. We are poorer. The sooner we get this, the sooner we understand and start to change our behaviors, the sooner we will be able to build true wealth. True wealth is embodied in our ability to sustainably provide for future generations (see “Could we solve two problems at once?” for a proposal to create true wealth). In society today we are consumed with consuming at the fastest possible rate for reasons that are, in the end, totally foolish.

I have maintained that we humans are ill-fit in terms of our inherent wisdom (sapience) when it comes to thinking about, and providing for, the future. We will, I have no doubts, consume away without real regard for the damage we do. We will use up the fossil fuels as fast as we possibly can in the name of profits. We will destroy the ability of the planet to support human life in the name of capitalism. And for what? So that a few rich bankers can prove to everyone how clever they are by virtue of their monetary wealth? I hope I can be witness to the day when those bankers are forced to eat their money. Bits in a computer's memory (where money now mostly resides) carry very few calories!

.

No comments :

Post a Comment