SUBHEAD: The Justice Department began an antitrust investigation of Monsanto and the seed industry as prices soar.

By William Neuman on 11 March 2010 in The New York Times -

(http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/12/business/12seed.html)

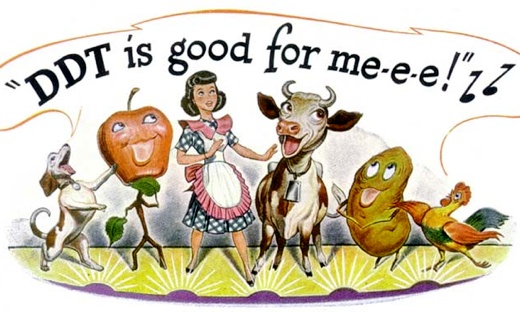

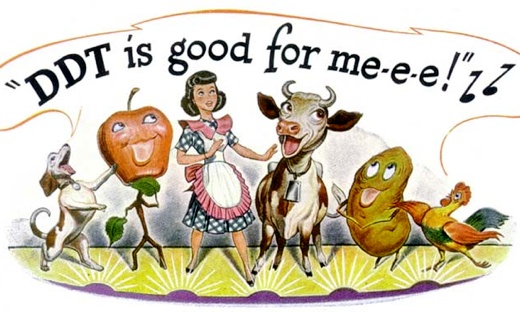

Image above: Detail of 1950's ad for DDT, developed by Monsanto, the company founded when the FDA was called the Bureau of Chemicals. From (http://allergykids.wordpress.com/2008/05/07/the-monopoly-of-the-food-supply-price-inflammation-and-one-corporations-allergy-to-labels)

By William Neuman on 11 March 2010 in The New York Times -

(http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/12/business/12seed.html)

Image above: Detail of 1950's ad for DDT, developed by Monsanto, the company founded when the FDA was called the Bureau of Chemicals. From (http://allergykids.wordpress.com/2008/05/07/the-monopoly-of-the-food-supply-price-inflammation-and-one-corporations-allergy-to-labels)

During the depths of the economic crisis last year, the prices for many goods held steady or even dropped. But on American farms, the picture was far different, as farmers watched the price they paid for seeds skyrocket. Corn seed prices rose 32 percent; soybean seeds were up 24 percent.

Such price increases for seeds — the most important purchase a farmer makes each year — are part of an unprecedented climb that began more than a decade ago, stemming from the advent of genetically engineered crops and the rapid concentration in the seed industry that accompanied it.

The price increases have not only irritated many farmers, they have caught the attention of the Obama administration. The Justice Department began an antitrust investigation of the seed industry last year, with an apparent focus on Monsanto, which controls much of the market for the expensive bioengineered traits that make crops resistant to insect pests and herbicides.

The investigation is just one facet of a push by the Obama administration to take a closer look at competition — or the lack thereof — in agriculture, from the dairy industry to livestock to commodity crops, like corn and soybeans.

On Friday, as the spring planting season approaches, Eric H. Holder Jr., the attorney general, and Tom Vilsack, the agriculture secretary, will speak at the first of a series of public meetings aimed at letting farmers and industry executives voice their ideas. The meeting, in Ankeny, Iowa, will include a session on the seed industry.

“I think most farmers would look to have more competition in the industry,” said Laura L. Foell, who raises corn and soybeans on 900 acres in Schaller, Iowa.

The Iowa attorney general, Tom Miller, has also been scrutinizing Monsanto’s market dominance. The company’s genetically engineered traits are in the vast majority of corn and soybeans grown in the United States, Mr. Miller said. “That gives them considerable power, and questions arise about how that power is used,” he said.

Critics charge that Monsanto has used license agreements with smaller seed companies to gain an unfair advantage over competitors and to block cheaper generic versions of its seeds from eventually entering the market. DuPont, a rival company, also claims Monsanto has unfairly barred it from combining biotech traits in a way that would benefit farmers.

In a recent interview at Monsanto’s headquarters in St. Louis, its chief executive, Hugh Grant, said that while his company might be the market leader, competition was increasing as the era of biotech crops matured.

“We were the first out of the blocks, and I think what you see now is a bunch of people catching up and aggressively competing, and I’m fighting with them,” Mr. Grant said. He said farmers chose the company’s products because they liked the results in the field, not because of any untoward conduct on Monsanto’s part.

Yet in a seed market that Monsanto dominates, the jump in prices has been nothing short of stunning.

Including the sharp increases last year, Agriculture Department figures show that corn seed prices have risen 135 percent since 2001. Soybean prices went up 108 percent over that period. By contrast, the Consumer Price Index rose only 20 percent in that period.

Many farmers have been willing to pay a premium price because the genetically engineered seeds that make up most of the market come with advantages. Genetic modifications for both corn and soybeans make the crops resistant to herbicides, simplifying weed control and saving labor, fuel and machinery costs. Many genetically engineered corn and cotton seeds also resist insect pests, which cuts down on chemical spraying.

Lee Quarles, a Monsanto spokesman, said the price increases were justified because the quality of the seeds had been going up, and new biotech traits kept being added. For example, he said, many corn varieties now include multiple genes to battle insect pests, raising their value.

Mr. Quarles said higher prices were justified because the traits saved farmers money and made their operations more efficient.

Monsanto began investing heavily in biotechnology in the 1980s — ahead of most other agricultural companies. In the mid-1990s, it became the first to widely market genetically engineered seeds for row crops, introducing soybeans containing the so-called Roundup Ready gene, which allowed plants to tolerate spraying of its popular Roundup weed killer. Soon after, it began selling corn seed engineered with a gene to resist insect pests.

The number of biotech plant traits has grown since then, and other large companies — including DuPont, Dow Chemical, Syngenta, BASF and Bayer CropScience — have gotten into the business. But Monsanto has taken advantage of its head start. Today more than 90 percent of soybeans and more than 80 percent of the corn grown in this country are genetically engineered. A majority of those crops contain one or more Monsanto genes.

As biotechnology has spread, Monsanto and its competitors have bought dozens of smaller seed companies, increasing the concentration of market power in the industry.

Monsanto sells its own branded seed varieties, like Dekalb in corn and Asgrow in soybeans, to farmers. But it has expanded its influence and profits by licensing those traits to hundreds of small seed companies, allowing them to incorporate the traits in the seeds they sell. It has also granted licenses to the other large trait developers, allowing them to create combinations of engineered traits in a process known as stacking.

Monsanto says that its licensing shows it is the opposite of a monopolist, encouraging rather than hampering competition.

But critics say the licenses give Monsanto excessive control. Seed company executives said the licenses were sometimes worded in a way that compelled them to sell Monsanto traits over those of its competitors. Mr. Quarles denied that, saying the contracts contain sales incentives typical of the industry.

Some of the most pointed accusations have come in a court battle between Monsanto and DuPont. Last year Monsanto sued its rival, saying DuPont had used a Monsanto trait to create a gene combination that was not permitted in its licensing agreement.

DuPont countered by charging that Monsanto was using its market power to strong-arm competitors and quash innovation that would benefit farmers and consumers.

In January, Monsanto won a partial victory. A federal judge ruled that the license barred DuPont from creating the gene stack. But the judge said that DuPont could move ahead with its antitrust claims, which, if successful, could potentially nullify the stacking ban.

DuPont made another accusation that caught the attention of farmers and regulators, saying that Monsanto was trying to head off the eventual entry into the marketplace of generic Roundup Ready seeds.

The company’s patent on the Roundup Ready trait in soybeans expires before the 2014 planting season, meaning that, just as in the pharmaceutical business, rivals would be free to sell a cheaper version. Farmers would also be free to save seed from one year to the next, a money-saving step they are now barred from taking.

But DuPont charged that Monsanto was trying to force seed companies to switch prematurely to its second-generation Roundup Ready soybeans and taking other steps to make the entry of generics more difficult.

Monsanto responded by announcing that it would not block companies from selling a generic version of Roundup Ready seeds. But farmers have continued to fret that cheaper generic seeds may be at risk.

See also:

Ea O Ka Aina: Monsanto Seed Business Role 3/15/10

.

Such price increases for seeds — the most important purchase a farmer makes each year — are part of an unprecedented climb that began more than a decade ago, stemming from the advent of genetically engineered crops and the rapid concentration in the seed industry that accompanied it.

The price increases have not only irritated many farmers, they have caught the attention of the Obama administration. The Justice Department began an antitrust investigation of the seed industry last year, with an apparent focus on Monsanto, which controls much of the market for the expensive bioengineered traits that make crops resistant to insect pests and herbicides.

The investigation is just one facet of a push by the Obama administration to take a closer look at competition — or the lack thereof — in agriculture, from the dairy industry to livestock to commodity crops, like corn and soybeans.

On Friday, as the spring planting season approaches, Eric H. Holder Jr., the attorney general, and Tom Vilsack, the agriculture secretary, will speak at the first of a series of public meetings aimed at letting farmers and industry executives voice their ideas. The meeting, in Ankeny, Iowa, will include a session on the seed industry.

“I think most farmers would look to have more competition in the industry,” said Laura L. Foell, who raises corn and soybeans on 900 acres in Schaller, Iowa.

The Iowa attorney general, Tom Miller, has also been scrutinizing Monsanto’s market dominance. The company’s genetically engineered traits are in the vast majority of corn and soybeans grown in the United States, Mr. Miller said. “That gives them considerable power, and questions arise about how that power is used,” he said.

Critics charge that Monsanto has used license agreements with smaller seed companies to gain an unfair advantage over competitors and to block cheaper generic versions of its seeds from eventually entering the market. DuPont, a rival company, also claims Monsanto has unfairly barred it from combining biotech traits in a way that would benefit farmers.

In a recent interview at Monsanto’s headquarters in St. Louis, its chief executive, Hugh Grant, said that while his company might be the market leader, competition was increasing as the era of biotech crops matured.

“We were the first out of the blocks, and I think what you see now is a bunch of people catching up and aggressively competing, and I’m fighting with them,” Mr. Grant said. He said farmers chose the company’s products because they liked the results in the field, not because of any untoward conduct on Monsanto’s part.

Yet in a seed market that Monsanto dominates, the jump in prices has been nothing short of stunning.

Including the sharp increases last year, Agriculture Department figures show that corn seed prices have risen 135 percent since 2001. Soybean prices went up 108 percent over that period. By contrast, the Consumer Price Index rose only 20 percent in that period.

Many farmers have been willing to pay a premium price because the genetically engineered seeds that make up most of the market come with advantages. Genetic modifications for both corn and soybeans make the crops resistant to herbicides, simplifying weed control and saving labor, fuel and machinery costs. Many genetically engineered corn and cotton seeds also resist insect pests, which cuts down on chemical spraying.

Lee Quarles, a Monsanto spokesman, said the price increases were justified because the quality of the seeds had been going up, and new biotech traits kept being added. For example, he said, many corn varieties now include multiple genes to battle insect pests, raising their value.

Mr. Quarles said higher prices were justified because the traits saved farmers money and made their operations more efficient.

Monsanto began investing heavily in biotechnology in the 1980s — ahead of most other agricultural companies. In the mid-1990s, it became the first to widely market genetically engineered seeds for row crops, introducing soybeans containing the so-called Roundup Ready gene, which allowed plants to tolerate spraying of its popular Roundup weed killer. Soon after, it began selling corn seed engineered with a gene to resist insect pests.

The number of biotech plant traits has grown since then, and other large companies — including DuPont, Dow Chemical, Syngenta, BASF and Bayer CropScience — have gotten into the business. But Monsanto has taken advantage of its head start. Today more than 90 percent of soybeans and more than 80 percent of the corn grown in this country are genetically engineered. A majority of those crops contain one or more Monsanto genes.

As biotechnology has spread, Monsanto and its competitors have bought dozens of smaller seed companies, increasing the concentration of market power in the industry.

Monsanto sells its own branded seed varieties, like Dekalb in corn and Asgrow in soybeans, to farmers. But it has expanded its influence and profits by licensing those traits to hundreds of small seed companies, allowing them to incorporate the traits in the seeds they sell. It has also granted licenses to the other large trait developers, allowing them to create combinations of engineered traits in a process known as stacking.

Monsanto says that its licensing shows it is the opposite of a monopolist, encouraging rather than hampering competition.

But critics say the licenses give Monsanto excessive control. Seed company executives said the licenses were sometimes worded in a way that compelled them to sell Monsanto traits over those of its competitors. Mr. Quarles denied that, saying the contracts contain sales incentives typical of the industry.

Some of the most pointed accusations have come in a court battle between Monsanto and DuPont. Last year Monsanto sued its rival, saying DuPont had used a Monsanto trait to create a gene combination that was not permitted in its licensing agreement.

DuPont countered by charging that Monsanto was using its market power to strong-arm competitors and quash innovation that would benefit farmers and consumers.

In January, Monsanto won a partial victory. A federal judge ruled that the license barred DuPont from creating the gene stack. But the judge said that DuPont could move ahead with its antitrust claims, which, if successful, could potentially nullify the stacking ban.

DuPont made another accusation that caught the attention of farmers and regulators, saying that Monsanto was trying to head off the eventual entry into the marketplace of generic Roundup Ready seeds.

The company’s patent on the Roundup Ready trait in soybeans expires before the 2014 planting season, meaning that, just as in the pharmaceutical business, rivals would be free to sell a cheaper version. Farmers would also be free to save seed from one year to the next, a money-saving step they are now barred from taking.

But DuPont charged that Monsanto was trying to force seed companies to switch prematurely to its second-generation Roundup Ready soybeans and taking other steps to make the entry of generics more difficult.

Monsanto responded by announcing that it would not block companies from selling a generic version of Roundup Ready seeds. But farmers have continued to fret that cheaper generic seeds may be at risk.

See also:

Ea O Ka Aina: Monsanto Seed Business Role 3/15/10

.

1 comment :

This information is incredible. I am grateful that this article is being shared here and also thankful to know there are countless independent small and large scale organic farmers out there taking the initiative to do their part in reducing the demand for these GMO seeds.

We are at such an interesting precipice as humans continue to rapidly reproduce almost as if we were a virus ourselves to our mother planet. There are so many more mouths to feed and traditional organic farming can only account for so much of this food production.

Not to stray too far off subject but this leads me to think of this major issue that truly needs to be addressed in regards to both healthy food being grown and taking care of our planet. We need to strongly consider actions for reducing the population growth of humans.

The concrete jungles, the GMO domination of staple crops, and the incredibly rapid population growth rate (and not to mention the realistic scarcity of fossil fuels looming) are really setting us up for an interesting future scenario indeed.

I appreciate this website so much for sharing this relevant information.

~Mahalo

Post a Comment