By Joann Macy on 17 June 2013 in Resilience.org-

(http://www.resilience.org/stories/2013-06-17/hearing-the-call)

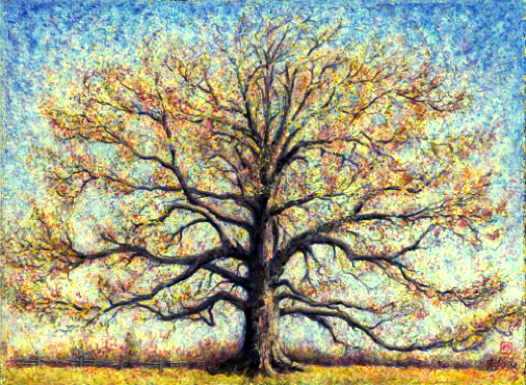

Image above: Soul of the Whole by Pat Silbert Waverly Street Gallery, Bethesda MD, USA. From original article (www.patsilbertpaintings.com).

This article is an edited excerpt from the introduction to Stories of the Great Turning, edited by Peter Reason and Melanie Newman, published by Vala Publications. This article originally appeared in Resurgence magazine, and is republished with permission from the author.

When you know where to look, you begin to see an unprecedented phenomenon now happening in this world of ours. Be they teachers in favelas, forest defenders, urban farmers, occupiers of Wall Street, designers of windmills, military resisters (the list goes on…), the fact is people from all walks of life are coming alive and coming together, impelled to create a more just and sustainable society.

In his book Blessed Unrest Paul Hawken presents this – what he calls The Movement With No Name – as the largest social movement of human history. Estimating the number of grassroots groups and nongovernmental organisations for social justice, Indigenous rights and environmental sanity, he suggests a figure of 2 million of us (as of 2007), and counting.

Each of these groups and organisations represents a yet vaster number of individuals who, in some way or another (and each uniquely in their own fashion), are hearing the call to widen the notions of their self-interest and act for the sake of life on Earth. In this defining moment, countless choices are being made, habits relinquished, friendships forged, and gateways opened to unforeseen collaborations and capacities.

These shape the stories that deserve to be told – stories of ordinary men, women and youngsters who are making changes in their minds, their lives and their communities, in order to lay the groundwork for this more just and sustainable world. These are the tales that we need to hear, and those who come after us will want them as well. For when future generations look back at this historical moment, they will see, more clearly than we can right now, just how revolutionary it is. They may well call it the time of the Great Turning.

For those of us living now it is easy to be unaware of the immensity of this transition – from an entrenched, militarised industrial growth society to a life-sustaining civilisation.

Mainstream education and mainstream media do not provide the tools for comprehending such a perspective. Yet social thinkers such as Lester Brown and Donella Meadows and others recognise this transition as the third major watershed in humanity’s journey, comparable in magnitude and scope to the agricultural and industrial revolutions. This is the essential adventure of our time.

Like all true revolutions, it belongs to the people. Its inspiring stories do not star titans of industry or party politicians, military generals or media celebrities. The power of this revolution lies in the fact that it comes from people of all ages and backgrounds as they engage in actions on behalf of life itself. Their motivation represents a remarkable expansion of allegiance beyond personal or group advantage. This wider sense of identity is a moral capacity more often associated with heroes and saints; but it now manifests everywhere on a practical and workaday plane.

From children restoring streams for salmon spawning, to inner-city neighbours planting community gardens, from forest defenders perched high in trees marked for illegal logging, to countless climate actions to limit greenhouse-gas emissions, an undreamt-of wave of human endeavour is under way.

Each of these engagements has its own intrinsic rewards, whether its initial goal is achieved or not.

And even when failing to reach the desired outcome, the gains can be invaluable in terms of all that has been learnt in the process – not only about the issue, but also about courage and co-creativity.

Still, it is easy to turn away from playing a part in the Great Turning. All of us are prey to the fear that it may be too late, and thus any effort is essentially hopeless. Any strategy we can mount seems so puny in comparison with the mighty systemic forces embedded in the military-industrial complex.

The accelerating pace of destruction and contamination may already be taking us beyond those tipping points where ecological and social systems unravel irreparably. Along with the Great Turning, the Great Unravelling is happening too, and there is no way to tell how the larger story will end.

So we learn again that hardest and most rewarding of lessons: how to make friends with uncertainty; how to pour your whole passion into a project when you can’t be sure it’s going to work. How to free yourself from dependence on seeing the results of your actions. These learnings are crucial, for living systems are ever unfolding in new patterns and connections. There is no point from which to foresee with clarity the possibilities to emerge under future conditions.

Instead of any blueprint of the future, we have this moment. In lieu of a sure-fire strategy to pull off the Great Turning, we can only fashion guidelines to help us keep going as best we can, and to stay on track with a simple faith in the goodness of life. Here are five of those guidelines that have already served a number of us over the years. Try them out, and make up some of your own.

1. Come from gratitude

We have received an inestimable gift: to be alive in this wondrous, self-organising universe with senses to perceive it, lungs that breathe it, organs that draw nourishment from it. And how amazing it is to be accorded a human life with self-reflective consciousness that allows us to make choices, letting us opt to take part in the healing of our world.

The very scope of the Great Turning is cause for gratitude as well, for it embraces the full gamut of human experience. Its three main dimensions include actions to slow down the destruction wrought by our political economy and its wars against humanity and Nature; new structures and ways of doing things, from holding land to growing food to generating energy; and a shift in consciousness to new ways of knowing, a new paradigm of our relation to each other and to the sacred living body of Earth. These dimensions are equally essential and mutually reinforcing. There are thousands of ways to take part in the Great Turning.

2. Don’t be afraid of the dark

This is a dark time filled with suffering, as old systems and previous certainties come apart. Like living cells in a larger body, we feel the trauma of our world. It is natural and even healthy that we do, for it shows we are still vitally linked in the web of life. So don’t be afraid of the grief you may feel, or of the anger or fear: these responses arise, not from some private pathology, but from the depths of our mutual belonging. Bow to your pain for the world when it makes itself felt, and honour it as testimony to our interconnectedness.

When the Zen poet Thich Nhat Hanh was asked: “What do we most need to do to save our world?” his questioners expected him to identify the best strategies to pursue for social and environmental causes. But Thich Nhat Hanh answered: “What we most need to do is to hear within us the sounds of the Earth crying.” When we learn to hear that, we discover that our pain for the world and our love for the world are one. And we are made stronger.

3. Dare to vision

We will never bring forth what we haven’t dared to dream or learnt to imagine. For those of us dwelling in a high-tech consumer society, replete with ever proliferating electronic distractions, the imagination is the most underdeveloped, even atrophied, of our mental capacities. Yet never has its juicy, enlivening power been more desperately needed than now.

So, think of how many aspects of our current reality started out as someone’s dream. There was a time when much of America was a British colony, when women didn’t have the vote and when the slave trade was seen as essential to the economy. To change something, we need to hold the possibility that it could be different. Author and coach Stephen Covey reminds us: “All things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.”

4. Link arms with others

Whatever it is that you’re drawn to do in the Great Turning, don’t even think of doing it alone. The hyper-individualism of our competitive industrialised culture has isolated people from each other, breeding conformity, obedience and an epidemic of loneliness. The good news of the Great Turning is that it is a team undertaking. It evolves out of countless spontaneous and synergistic interactions as people discover their common goal and their different gifts. Paul Hawken sees this amazing emergence at the grassroots level as an immune response of the living Earth to the crises now confronting us.

Many models of affinity groups and study-action have emerged in recent decades, offering methods for learning, strategising and working together. They help us uncover confidence in ourselves as well as in each other.

5. Act your age

Now is the time to clothe ourselves in our true authority. Every particle in every atom of every cell in our body goes back to the primal flaring forth of space and time. In that sense you are as old as the universe, with an age of about 14 billion years. This current body of yours has been being prepared for this moment by Earth for some 4 billion years, so you have an absolute right to step forward and act on Earth’s behalf. When you are speaking up at a city council meeting, or protecting a forest from demolition, or testifying at a hearing on nuclear waste, you are doing that not out of some personal whim or virtue, but from the full authority of your 14 billion years.

The beauty of the Great Turning is that each of us takes part in distinctive ways. Given our different circumstances and with our different dispositions and capacities, our stories are all unique. All have something fresh to reveal. All can help inspire others. And that’s why we need these stories…

.