SUBHEAD: Human energy systems may be closer than we think to a virtuous tipping point.

By Fred Pearce on 13 January 2015 for Yale 360 -

(http://e360.yale.edu/feature/could_global_tide_be_starting_to_turn_against_fossil_fuels/2837/)

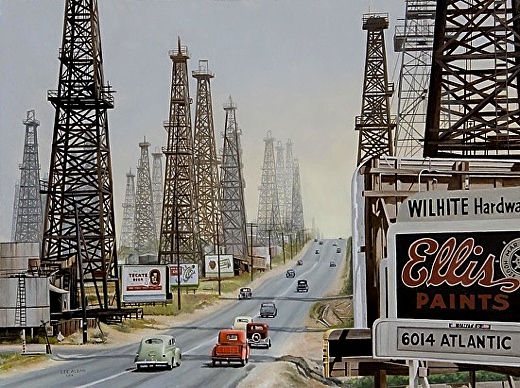

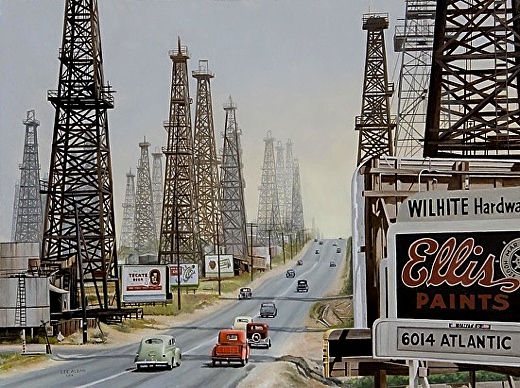

Image above: Oil painting by Lee Alban from 1940's photograph of Long Beach CA oil rigs. From (http://leealban.com/workszoom/1461238).

From an oil chill in the financial world to the recent U.S.-China agreement on climate change, recent developments are raising a question that might once have been considered unthinkable: Could this be the beginning of a long, steady decline for the oil and coal industries?

Boom may be turning to bust for fossil fuels. Market forces are combining with the prospect of new limits on carbon emissions from major economies such as China and the United States to prick the carbon bubble. Many analysts are now suggesting that — with prices falling and production costs rising — the coming year could be the moment when investors realize the game is up for the coal and oil industries.

Nations found it hard to make progress at UN climate negotiations in Lima last year, making many observers skeptical of the prospects of a legally-binding deal to cut emissions of carbon dioxide as planned in Paris at the end of this year.

But, with or without a deal, the tide is turning against investing in fossil fuels, says Jeremy Leggett, one of the most durable climate campaigners of the past quarter-century, who is now chair of Carbon Tracker, a think tank on finance, energy, and climate.

“Watching the wave of investor pressure wash across carbon-fuel capital expenditure in the closing months of 2014, I now think this is how the carbon war can be won,” Leggett, who formerly was science director for Greenpeace and founder of a successful British solar energy company, says. “The way things are shaping up, negotiations in Paris might be playing catch-up to the markets.”

Perhaps the most totemic sign of the times came in September when the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a philanthropic body set up by the heirs to the Standard Oil fortune, announced that it would pull its money out of fossil fuels, beginning with coal and tar sands.

But the alarm bells are ringing for the masters of the financial universe, too.

The governor of the Bank of England, Canadian banker Mark Carney, warned repeatedly during 2014 that what he termed “stranded assets” are a growing risk for fossil-fuel companies. “The majority of proven coal, oil, and gas reserves may be considered ‘unburnable’ if global temperature increases are to be limited to two degrees Celsius,” he said in a letter to the British parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee in October, referring to the widely accepted temperature threshold for avoiding the worst effects of climate change.

Carney, who is also chairman of the G20 Financial Stability Board, which monitors the global financial system, told a World Bank seminar that financiers in denial about climate change were guilty of creating a “tragedy of horizons.” He announced that in 2015 the Bank of England’s Finance Policy Committee would investigate whether risks to the value of “unburnable” fossil fuels assets could undermine financial stability in the way that sub-prime mortgages crashed the global economy in 2008.

At every level, from macroeconomic management to the day-to-day business of money markets, the tide is turning against fossil fuels.

The first signs of a fossil-fuel bust emerged early last year with growing evidence that the decade-long boom in global coal demand was peaking. As we reported here in June, this is mainly a result of changes in the Chinese economy, where energy efficiency is improving fast, growth is shifting to low-carbon activities, and public anger about smog is forcing the shutdown of coal-fired power plants in Beijing and elsewhere.

This trend was reinforced by the reciprocal climate deal that China struck with the Obama administration in November, under which China agreed to peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and put a cap on coal burning by 2020. In fact, some analysts now predict that Chinese coal burning could begin to decline as early as next year.

This is a global game-changer. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, China was responsible for more than 80 percent of the growth in global coal burning since 2000, and currently burns half of the world’s coal. With coal demand already starting to decline in the U.S. and other developed countries, the coal boom may be over.

Investors are already running for cover. From Australia to Mozambique, new coal mines costing billions of dollars are being mothballed, and major mining firms are getting out of coal, according to Tim Buckley of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In the most dramatic example, the Anglo-Australian giant Rio Tinto in July sold its stake in the world’s most expensive coal mine in Mozambique — effectively writing off more than $3 billion.

And now the same specter looms for oil. Oil prices have halved since June, with the benchmark Brent crude trading earlier this week at less than $50 a barrel. If such prices are maintained, this would leave many reserves unviable, putting severe strains on even the largest oil companies, according to James Leaton, research director at Carbon Tracker.

Leaton calculates that major companies have earmarked more than a trillion dollars of investment in projects between now and 2025 that require an international oil price of at least $95 a barrel before they make a profit.

Most of these high-price reserves are on the industry’s new frontiers — in the Arctic, deep ocean waters, or unconventional sources like the Alberta tar sands, where three major projects were deferred in 2014 because of falling oil prices.

Brazil’s oil giant Petrobras, whose investments in deep-sea oil in the South Atlantic have made it the most indebted company in the world, is reportedly close to going bust. Leaton reports that many of its new offshore fields have a break-even price of $120 a barrel.

Of course oil prices may rise again. Some analysts believe the prices are currently being kept artificially low by over-production in Saudi Arabia, aimed perhaps at scuppering the U.S. shale-oil industry.

But many see a long-term trend and expect a rash of business failures, as companies heavily invested in high-cost oil reserves face a world in which demand is restricted by growing concern over climate change and prices are tumbling in consequence.

Analyst Mark Lewis of Kepler Cheuvreaux, a Swiss private bank, calculates that to meet emissions targets that could cap global warming at two degrees Celsius will mean lost fossil-fuel revenues of no less than $28 trillion in the coming two decades. He argues that, in a world of climate change, investors should urgently stress-test the business strategies of big oil against “carbon risk.”

Many big oil companies, including Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP, deny that any threat exists. “We do not believe that any of our proven assets will become stranded,” said Shell in May last year in a letter to shareholders. The company said it simply does not believe the world will constrain carbon emissions enough.

But in November, former BP chief executive Lord John Browne said many oil and gas companies were still in denial about climate change because “they do not want to acknowledge an existential threat to their business.”

Oil is in a double bind, says Lewis. If prices are low, then opening up new reserves is unviable; if prices are high, then many customers will switch to alternatives, or simply invest in energy efficiency.

Fossil fuel investments could become the “sub-prime assets of the future,” warned British energy secretary Ed Davey. No wonder investors are starting to ask serious questions about the companies they have traditionally regarded as secure places to put their money.

All this looks like great news for the climate. And there are other hopeful signs. The global economy is on a long-term trend to greater efficiency in the use of energy. Carbon emissions for every dollar of GDP are 37 percent below those in 1990. The carbon intensity of the Chinese economy, while still twice that of the United States, has fallen 25 percent in less than a decade.

Meanwhile, as the costs of producing fossil fuels rise, those for renewables are in sharp decline. Solar panels cost only a tenth what they did a decade ago. Only the perpetuation of heavy state subsidies — estimated by the IEA at more than half a trillion dollars a year — has maintained the primacy of fossil fuels.

All this is leading some economists to argue that the idea of nations needing to share the economic “burden” of curbing CO2 emissions is becoming outdated. Fossil fuels are becoming the burden, they say. Nations should be competing to decarbonize their economies as a means to maximise economic growth.

Lord Nicholas Stern of the London School of Economics — author in 2006 of the influential Stern Review of the economics of climate change — told climate negotiators in Lima that “the path to a low-carbon economy can be highly attractive.” Rather than fighting for the right to emit ever more CO2 as their economies grow, poor nations should be demanding “the right to sustainable development,” he said.

Such optimistic thinking has yet to be reflected in the actual climate negotiations, which remain mired in battles about burden sharing. But they do explain why many nations — among them Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, China, the U.S., and the European Union — have made unilateral commitments to curbing their emissions. These commitments are usually based on carbon-intensity targets, which the countries regard as being in their national self-interest.

And they also suggest that the fossil-fuel boom is drawing to a close.

Nothing is certain. There are several jokers in the pack. One concern is the explosion of interest in extracting natural gas from shale. While natural gas is much less carbon-intense than coal or oil, a burgeoning industry based on cheap shale gas could easily swamp those gains in the long run.

Another concern is that while China may be taking a lower-carbon path of economic growth, other fast-industrializing nations may not. India remains heavily committed to burning coal and has abundant domestic reserves, though the new government of Narendra Modi has announced plans to bring electricity to 400 million rural Indians through mini-grids run on solar energy.

Finally, there is the climate system itself. Even if the world can break its addiction to fossil fuels and peak carbon emissions soon, it could still be too late to prevent devastating climate change.

The most recent report on climate science from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made clear that we still don’t know how sensitive the climate system is to CO2, nor what disruptive feedbacks may emerge as ecosystems dry out, ice caps disappear, and permafrost melts — all of which could potentially accelerate warming beyond human control.

Human energy systems may be closer than we think to a virtuous tipping point. But nature’s tipping point could yet have the last word.

.

By Fred Pearce on 13 January 2015 for Yale 360 -

(http://e360.yale.edu/feature/could_global_tide_be_starting_to_turn_against_fossil_fuels/2837/)

Image above: Oil painting by Lee Alban from 1940's photograph of Long Beach CA oil rigs. From (http://leealban.com/workszoom/1461238).

From an oil chill in the financial world to the recent U.S.-China agreement on climate change, recent developments are raising a question that might once have been considered unthinkable: Could this be the beginning of a long, steady decline for the oil and coal industries?

Boom may be turning to bust for fossil fuels. Market forces are combining with the prospect of new limits on carbon emissions from major economies such as China and the United States to prick the carbon bubble. Many analysts are now suggesting that — with prices falling and production costs rising — the coming year could be the moment when investors realize the game is up for the coal and oil industries.

Nations found it hard to make progress at UN climate negotiations in Lima last year, making many observers skeptical of the prospects of a legally-binding deal to cut emissions of carbon dioxide as planned in Paris at the end of this year.

But, with or without a deal, the tide is turning against investing in fossil fuels, says Jeremy Leggett, one of the most durable climate campaigners of the past quarter-century, who is now chair of Carbon Tracker, a think tank on finance, energy, and climate.

“Watching the wave of investor pressure wash across carbon-fuel capital expenditure in the closing months of 2014, I now think this is how the carbon war can be won,” Leggett, who formerly was science director for Greenpeace and founder of a successful British solar energy company, says. “The way things are shaping up, negotiations in Paris might be playing catch-up to the markets.”

Perhaps the most totemic sign of the times came in September when the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a philanthropic body set up by the heirs to the Standard Oil fortune, announced that it would pull its money out of fossil fuels, beginning with coal and tar sands.

But the alarm bells are ringing for the masters of the financial universe, too.

The governor of the Bank of England, Canadian banker Mark Carney, warned repeatedly during 2014 that what he termed “stranded assets” are a growing risk for fossil-fuel companies. “The majority of proven coal, oil, and gas reserves may be considered ‘unburnable’ if global temperature increases are to be limited to two degrees Celsius,” he said in a letter to the British parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee in October, referring to the widely accepted temperature threshold for avoiding the worst effects of climate change.

Carney, who is also chairman of the G20 Financial Stability Board, which monitors the global financial system, told a World Bank seminar that financiers in denial about climate change were guilty of creating a “tragedy of horizons.” He announced that in 2015 the Bank of England’s Finance Policy Committee would investigate whether risks to the value of “unburnable” fossil fuels assets could undermine financial stability in the way that sub-prime mortgages crashed the global economy in 2008.

At every level, from macroeconomic management to the day-to-day business of money markets, the tide is turning against fossil fuels.

The first signs of a fossil-fuel bust emerged early last year with growing evidence that the decade-long boom in global coal demand was peaking. As we reported here in June, this is mainly a result of changes in the Chinese economy, where energy efficiency is improving fast, growth is shifting to low-carbon activities, and public anger about smog is forcing the shutdown of coal-fired power plants in Beijing and elsewhere.

This trend was reinforced by the reciprocal climate deal that China struck with the Obama administration in November, under which China agreed to peak its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and put a cap on coal burning by 2020. In fact, some analysts now predict that Chinese coal burning could begin to decline as early as next year.

This is a global game-changer. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, China was responsible for more than 80 percent of the growth in global coal burning since 2000, and currently burns half of the world’s coal. With coal demand already starting to decline in the U.S. and other developed countries, the coal boom may be over.

Investors are already running for cover. From Australia to Mozambique, new coal mines costing billions of dollars are being mothballed, and major mining firms are getting out of coal, according to Tim Buckley of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In the most dramatic example, the Anglo-Australian giant Rio Tinto in July sold its stake in the world’s most expensive coal mine in Mozambique — effectively writing off more than $3 billion.

And now the same specter looms for oil. Oil prices have halved since June, with the benchmark Brent crude trading earlier this week at less than $50 a barrel. If such prices are maintained, this would leave many reserves unviable, putting severe strains on even the largest oil companies, according to James Leaton, research director at Carbon Tracker.

Leaton calculates that major companies have earmarked more than a trillion dollars of investment in projects between now and 2025 that require an international oil price of at least $95 a barrel before they make a profit.

Most of these high-price reserves are on the industry’s new frontiers — in the Arctic, deep ocean waters, or unconventional sources like the Alberta tar sands, where three major projects were deferred in 2014 because of falling oil prices.

Brazil’s oil giant Petrobras, whose investments in deep-sea oil in the South Atlantic have made it the most indebted company in the world, is reportedly close to going bust. Leaton reports that many of its new offshore fields have a break-even price of $120 a barrel.

Of course oil prices may rise again. Some analysts believe the prices are currently being kept artificially low by over-production in Saudi Arabia, aimed perhaps at scuppering the U.S. shale-oil industry.

But many see a long-term trend and expect a rash of business failures, as companies heavily invested in high-cost oil reserves face a world in which demand is restricted by growing concern over climate change and prices are tumbling in consequence.

Analyst Mark Lewis of Kepler Cheuvreaux, a Swiss private bank, calculates that to meet emissions targets that could cap global warming at two degrees Celsius will mean lost fossil-fuel revenues of no less than $28 trillion in the coming two decades. He argues that, in a world of climate change, investors should urgently stress-test the business strategies of big oil against “carbon risk.”

Many big oil companies, including Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP, deny that any threat exists. “We do not believe that any of our proven assets will become stranded,” said Shell in May last year in a letter to shareholders. The company said it simply does not believe the world will constrain carbon emissions enough.

But in November, former BP chief executive Lord John Browne said many oil and gas companies were still in denial about climate change because “they do not want to acknowledge an existential threat to their business.”

Oil is in a double bind, says Lewis. If prices are low, then opening up new reserves is unviable; if prices are high, then many customers will switch to alternatives, or simply invest in energy efficiency.

Fossil fuel investments could become the “sub-prime assets of the future,” warned British energy secretary Ed Davey. No wonder investors are starting to ask serious questions about the companies they have traditionally regarded as secure places to put their money.

All this looks like great news for the climate. And there are other hopeful signs. The global economy is on a long-term trend to greater efficiency in the use of energy. Carbon emissions for every dollar of GDP are 37 percent below those in 1990. The carbon intensity of the Chinese economy, while still twice that of the United States, has fallen 25 percent in less than a decade.

Meanwhile, as the costs of producing fossil fuels rise, those for renewables are in sharp decline. Solar panels cost only a tenth what they did a decade ago. Only the perpetuation of heavy state subsidies — estimated by the IEA at more than half a trillion dollars a year — has maintained the primacy of fossil fuels.

All this is leading some economists to argue that the idea of nations needing to share the economic “burden” of curbing CO2 emissions is becoming outdated. Fossil fuels are becoming the burden, they say. Nations should be competing to decarbonize their economies as a means to maximise economic growth.

Lord Nicholas Stern of the London School of Economics — author in 2006 of the influential Stern Review of the economics of climate change — told climate negotiators in Lima that “the path to a low-carbon economy can be highly attractive.” Rather than fighting for the right to emit ever more CO2 as their economies grow, poor nations should be demanding “the right to sustainable development,” he said.

Such optimistic thinking has yet to be reflected in the actual climate negotiations, which remain mired in battles about burden sharing. But they do explain why many nations — among them Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, China, the U.S., and the European Union — have made unilateral commitments to curbing their emissions. These commitments are usually based on carbon-intensity targets, which the countries regard as being in their national self-interest.

And they also suggest that the fossil-fuel boom is drawing to a close.

Nothing is certain. There are several jokers in the pack. One concern is the explosion of interest in extracting natural gas from shale. While natural gas is much less carbon-intense than coal or oil, a burgeoning industry based on cheap shale gas could easily swamp those gains in the long run.

Another concern is that while China may be taking a lower-carbon path of economic growth, other fast-industrializing nations may not. India remains heavily committed to burning coal and has abundant domestic reserves, though the new government of Narendra Modi has announced plans to bring electricity to 400 million rural Indians through mini-grids run on solar energy.

Finally, there is the climate system itself. Even if the world can break its addiction to fossil fuels and peak carbon emissions soon, it could still be too late to prevent devastating climate change.

The most recent report on climate science from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change made clear that we still don’t know how sensitive the climate system is to CO2, nor what disruptive feedbacks may emerge as ecosystems dry out, ice caps disappear, and permafrost melts — all of which could potentially accelerate warming beyond human control.

Human energy systems may be closer than we think to a virtuous tipping point. But nature’s tipping point could yet have the last word.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment