To cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival. —Wendell Berry

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves. —Victor Frankl

Not long ago, a rocket took off from a Florida launching pad taking Americans to the moon. The moon shot signified to many that Americans could do anything we set our minds to.

Today, in another part of Florida, toxic oil is washing up on beaches. Hundreds of miles of Gulf Coast have been devastated, and people whose resilience was tested by Hurricane Katrina are being tested even more severely today. There are good reasons to believe many more of us will have our resilience tested in coming months and years.

Future historians may see this time as a turning point for Western civilization. In the popular zeitgeist, there is much discussion of end times. Millennialists await the Rapture. New Agers point to prophecies that 2012 will mark the end of the world (but perhaps the beginning of another one).

The End Of Cheap Oil

More secular folks also warn of big changes ahead. Concern about energy supplies is one reason. Author and energy analyst Michael Klare says we have already extracted the oil that’s easy to get; from here on, we’re into the “Age of Tough Oil,” and the human, environmental, and financial cost of each additional barrel of oil will be higher than the last.

Fossil fuels contain millions of years of stored sunlight. A liter of oil, according to Transition Towns founder Rob Hopkins, is the energy equivalent of five weeks of hard human labor. In a society that relies on fossil fuels for transportation, food, warmth, and light, the loss of an abundant and inexpensive form of high-quality energy is no small thing. There simply isn’t anything else out there quite like it, and many geologists believe we are at, or close to, the peak production of this powerful source of energy.

The U.S. Military agrees:

“Assuming the most optimistic scenario for improved petroleum production through enhanced recovery means, the development of non-conventional oils (such as oil shales or tar sands) and new discoveries, petroleum production will be hard pressed to meet the expected future demand” - says the Joint Operating Environment 2010, published by the United States Joint Forces Command.

This is not to say that oil will suddenly become unavailable. It does mean getting the oil we depend on will exact a higher and higher toll on people and the environment. Just look at the devastation caused by tar sands development in Canadian forests, the oil spills in the Gulf and now Michigan, and the impact on people as far flung as the Niger Delta and the Amazon.

It also means oil prices are likely to continue rising, especially if the economy starts to expand again, and with China and India’s new energy purchasing power.

Even if we could get ever-increasing quantities of fossil fuels (by using even more coal, for example), we have the problem of climate change. World leaders meeting in Copenhagen failed to come to terms with the biggest threat humans have ever faced—the possibility that runaway climate change could make the Earth uninhabitable.

Scientists point out that the amount of carbon already in the atmosphere will cause further disruption before the climate stabilizes, and no one knows where it will stabilize—whether the new climate will be anything like the one we count on to water our crops, maintain stable coastlines, and provide adequate supplies of drinking water.

The Economy

On the economic side, corporations have come through the global financial crisis they instigated with bigger profits than ever. But the Main Street economy of real goods and services, with jobs for ordinary people, remains stalled. Decades of tax cuts to the wealthy and the outsourcing of manufacturing have hollowed out the real economy. Our infrastructure is breaking down after years of maintenance deferred by governments starved of tax dollars.

Our military is overextended, too, in its mission to ensure U.S. access to oil and other resources. The costs to wounded and traumatized members of the military and those who care for them, to civilians caught in the battles, to taxpayers, and to future generations have yet to be calculated.

We now have diminished resources to respond to the intertwined economic and energy crises. And our democratic institutions are so compromised by big-money interests—and the media, think tanks, and politicians they control—that these foundational issues aren’t even on the political agenda.

This set of crises may be severe enough to throw our way of life into chaos and decline. We don’t know. In quiet conversations, many admit that they are learning to grow food and wondering how their children will survive life on a very different planet.

For some, of course, the chaos is already here. If you are a fisherman on the Louisiana Coast, a young job seeker in Detroit, a laid-off steelworker in the Ohio Valley, or a wounded Marine just back from Afghanistan, you may already be living in chaos. Some impoverished communities have been in crisis for decades.

The political Right frames the turmoil people are experiencing as a reason to hate immigrants, liberals, or people they say are “moving ahead of you to the front of the line.”

Building Community Resilience

But in communities everywhere, you’ll find people who are working instead to bring people together. They are building their own resilience, and that of their families and communities, so they are better able to withstand the hardships that are already here and those that may be coming. These are not futile attempts to bring back a way of life that is on its way out. Nor is this the bunker mentality of survivalists who look to save themselves regardless of what happens to others. Instead, these are creative, common-sense, low-tech approaches to meeting people’s needs now while planting the seeds of a more sustainable world for everyone.

Food is the most popular example. Across the country, a local food movement has taken off. More and more people are planting backyard gardens, building greenhouses, raising chickens and bees, and starting farmers markets—not just because fresh and local is delicious and cool. These efforts are, in some places, a response to the lack of fresh and healthy food in urban and rural “food deserts.” Food self-reliance is one way people are seeking security and community in an uncertain world.

Those looking for a more direct response to the dual crises of climate change and peak oil are turning to the Transition Town movement. Started by Rob Hopkins, a permaculture activist in the United Kingdom, this movement has spread to hundreds of communities in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, and Sweden, and more than 70 communities in the United States (where hundreds more are, in Transition parlance, “mulling” it over). People are joining who might not have signed up for an environmental or social justice project, but do want to build greater resilience to make it through tough times. Each Transition initiative is autonomous; each is engaged in studying what it means to move to a post-petroleum world; and most are creating spaces for skill-sharing, food production, and various experiments in resilience.

Other efforts do not explicitly link themselves to concerns about peak oil and climate change. But the goals of community resilience and a sustainable future are often in the background as people start up bicycle repair co-ops, neighborhood energy projects, building materials re-use centers, DIY skill-sharing gatherings, swap meets, and eco-villages. Like Transition initiatives, these projects meet immediate needs, raise spirits, and increase people’s chances of thriving during hard times.

Does working locally mean giving up on national policy change?

Community resilience projects can actually help build the political will to move society in more sustainable directions. They remind us that we can make history—starting where we live—and not just be subjected to the decisions of those in power.

As we learn to work together, learn what works, and learn that we have power, we are better able to insist on larger-scale change.

And we need that political clout to divert highway dollars to bicycle paths and efficient mass transit, and to put a halt to sprawl and build smart, walkable communities instead. We may even be able to bring back the American can-do spirit that made that moon shot possible. The new Apollo Alliance aims at making the transition from oil-addicted to clean and sustainable through massive investment in clean energy, green jobs, and energy efficiency.

Three Places to Start

Where do you start to build resilience? The YES! team identified three concepts that we believe can guide a no-regrets approach:

1. Build skills. Many transition initiatives start with learning and teaching skills that are valuable to yourself and others, and that can be practiced without harm to people or nature. If you can repair something, make something, or grow something, offer first aid or do low-tech mechanics, raise farm animals or rig up a solar oven, you can meet some of your immediate needs and swap with neighbors.

Many people had these skills in our grandparents’ generation. Consider drawing on elders to teach the practical skills they know, perhaps swapping for the skills young people know.

Also essential are the interpersonal skills that help people work together to get things done and to resolve conflicts.

2. Learn to live within local means. Work toward replacing products and services brought in from long distances with things you can do, make, harvest, or repurpose locally. Consider introducing small-scale animal husbandry, nut and fruit trees, and food processing facilities. Develop local, clean sources of energy. Help restore natural systems so they can be productive and resilient into the future. Use resources frugally and efficiently, and design things to last and to be reused or repurposed.

Include culture and entertainment, and provide opportunities for local artists and performers.

Set it up so people with little cash are included from the start. Develop means to barter, swap, and share. This will help restore your community’s economy, keep the flow of wealth local, and include the unemployed and low-wage workers.

This is a good time to look around and notice who your neighbors are, and to begin building systems of mutual support. This collaboration doesn’t need to be framed by dire warnings about the collapse of civilization. It can be as simple as sharing tools, planting a garden together, or holding a neighborhood potluck. If you start by reaching across class and race lines and across “culture war” divides, you will build a strong foundation for action. When things get difficult, the person who can offer the most may be the guy you argue with about politics but who knows how to fix things. Or it could be the young woman who knows how to bring people together in a song, or the grandmother who remembers how things used to be made by hand.

3. Imagine, adapt, celebrate. Building your personal resilience will increase the chances that you can help loved ones and the broader community during difficult times.

Get physically fit and healthy, and minimize dependence on high-tech medicine and pharmaceuticals.

Get out of debt.

Hone your ability to observe and think for yourself—turn off the pundits, talk to your neighbors, and make up your own mind.

Build a tolerance for uncertainty. A spiritual practice or a calming practice can help you remain centered in times of rapid change.

This may be a time of change, but it needn’t be a time of despair. After all, the enormously expensive (and destructive) way of life we have been living did not bring much happiness or health. By putting life-giving values first, we could well find more rewarding ways of living.

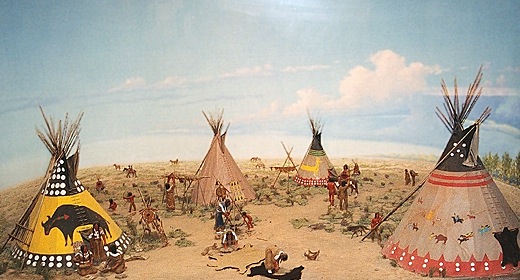

You can begin building more joyous ways of life by making the resilience work itself come alive. Encourage imagination and creativity. Have parties. Create liberated spaces. Celebrate at the drop of a hat. Communities throughout the world share music, dance, and storytelling, in secular and sacred contexts. From Appalachian square dances to Mardi Gras parades, from Native American Sun Dance to holy communion, gatherings and celebrations are the glue that hold a community together.

No Regrets

We don’t know what the future holds. Maybe in our lifetimes, nothing much will change. Although it’s unlikely, maybe offshore drilling, tar-sands oil, energy efficiency, and coal mining will keep our fossil fuel-based economy chugging along, and climate change will be mild enough that we can adapt.

The “no regrets” actions in this issue are worth taking in any case. They are already helping rebuild abandoned communities, like Detroit, as well as those newly devastated by foreclosures and joblessness. They minimize our reliance on natural resources found under other people’s soils and in other people’s rainforests, thus reducing the need to maintain the world’s most costly military empire. They contribute to an economic renewal based on systems that provide things people actually need, instead of throwaways that we only want because of ads. And these initiatives will make us healthier, more connected to other people and to the Earth, and probably happier. There is nothing here you would regret doing. You can think of this as an insurance policy that pays you premiums.

If things do fall apart, taking these actions could mean that people in the future will find the seeds of a new future already planted, literally, in the form of diverse crop strains and livestock, bees, and fruit and nut trees. Local renewable energy sources may not be able to support an energy-extravagant lifestyle, but they may be enough to light the nights, warm us through winter, and keep people in communication with one another and with the vast knowledge commons humanity has built over generations.

We may not have high-tech derivatives trading and landings on the moon. But people may develop greater wisdom along with skills for meeting family and community needs, for getting along, and for exchanging fairly, so that everyone’s gift is welcomed, and everyone has enough.

With that as a foundation, the decline of the industrial/oil era need not mean catastrophe. Instead it could mean we work together to build a wiser era, rooted in place and founded in community.

No comments :

Post a Comment