The Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan is unmatched in natural beauty, cultural richness and inspiring self-reflection. From the kingdom’s unique place in the world now arises economic and social questions that are of pressing interest to the rest of the planet.

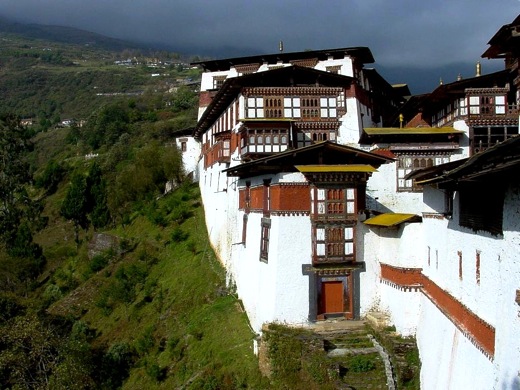

Bhutan’s rugged geography fostered a hardy population of farmers and herdsmen, and helped cement a strong Buddhist culture, closely connected in history with Tibet. The population is sparse, about 700,000 people on territory the size of France, with agricultural communities nestled in deep valleys and a few herdsmen in the high mountains.Each valley is guarded by a dzong, or fortress, which includes monasteries and temples, all dating back centuries and exhibiting a masterful combination of sophisticated architecture and fine arts.

Bhutan’s economy of agriculture and monastic life remained self-sufficient, poor and isolated until recent decades, when a series of remarkable monarchs began to guide the country towards technological modernisation (roads, power, modern health care and education), international trade and political democracy.What is incredible is the thoughtfulness with which Bhutan is approaching this process of change, and how Buddhist thinking guides it. Bhutan is asking itself the question that everyone must ask: how can economic modernisation be combined with cultural robustness and social well-being?

In Bhutan, the economic challenge is not growth in GDP but in gross national happiness (GNH). I went to Bhutan to understand better how GNH is being applied. There is no formula, but, befitting the seriousness of the challenge and Bhutan’s deep tradition of Buddhist reflection, there is an active and important process of national deliberation. Therein lies the inspiration for all of us. Part of Bhutan’s GNH revolves, of course, around meeting basic needs – improved health care, reduced maternal and child mortality, greater educational attainment and better infrastructure, especially electricity, water and sanitation.

This focus on material improvement aimed at meeting those goals makes sense for a country at Bhutan’s relatively low income level.Yet GNH goes well beyond broad-based, pro-poor growth. Bhutan is also asking how economic growth can be combined with environmental sustainability – a question it has answered in part through an immense effort to protect the country’s vast forest cover and unique biodiversity. It is asking how it can preserve its traditional equality and foster its unique cultural heritage.

And it is asking how individuals can maintain their psychological stability in an era of rapid change, marked by urbanisation and an onslaught of global communication in a society that had no televisions until a decade ago.I came to Bhutan after hearing an inspiring speech by Jigme Thinley, the country’s prime minister, at the 2010 Delhi Summit on Sustainable Development. Mr Thinley had made two compelling points. The first concerned the environmental devastation that he could observe, including the retreat of glaciers and the loss of land cover, as he flew from Bhutan to India.

The second was about the individual and the meaning of happiness. Mr Thinley put it simply: we are finite and fragile physical beings. How much “stuff” – fast foods, TV commercials, large cars, new gadgets and latest fashions – can we stuff into ourselves without deranging our own psychological well-being?For the world’s poorest countries, such questions are not the most pressing. Their biggest and most compelling challenge is to meet citizens’ basic needs. But for more and more countries, Mr Thinley’s reflection on the ultimate sources of well-being is not only timely, but also urgent.

Everybody knows that hyper-consumerism, as is common in the US, can destabilise social relations and lead to aggressiveness, loneliness, greed and overwork. What is perhaps less recognised is how those trends have accelerated in the US in recent decades. This may be the result of, among other things, the increasing and now relentless onslaught of advertising and public relations.The question of how to guide an economy to produce sustainable happiness, combining material well-being with human health, environmental conservation, and psychological and cultural resilience, needs to be addressed everywhere.

Bhutan has many things going its way. The country will be able to increase exports of clean hydropower to India, thereby sustainably earning foreign exchange to fund education, health care and infrastructure. The country is also intent on ensuring that the benefits of growth reach all of the population, regardless of region or income level.The key for Bhutan is to regard GNH as an enduring quest rather than as a simple checklist. Its Buddhist tradition understands happiness not as an attachment to goods and services but as the result of the serious work of inner reflection and compassion towards others.

Bhutan has embarked on this serious journey. The rest of the world’s economies should do the same.• Jeffrey D Sachs is a professor of economics and the director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. He is also a special adviser to the UN secretary general on the Millennium Development Goals

.

1 comment :

Very true. During the past 3 years I have been in Bhutan 4 times and experienced the warmth of human relations and compassion. Western powers are trying to break in with their products to start developing consumerism and changing the Bhutanese society to their own image, but luckily the Bhutanese government resists. Respect for each other, respect for the traditions, respect for the culture and respect for the leaders - is is a very simple recipe. Perhaps we would achieve much more with the same than with the sanctions, embargoes, threats and wars.

János Samu

Post a Comment