SUBHEAD: How secure is our civilization’s accumulated knowledge?

By Richard Heinberg on 7 October 2009 in Post Carbon Institute -

[IB Editor's Note: This is the concluding portion of the original article. To see the whole article click on the link above.]

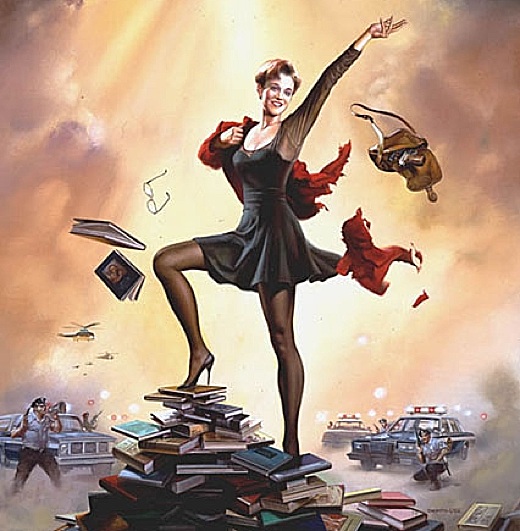

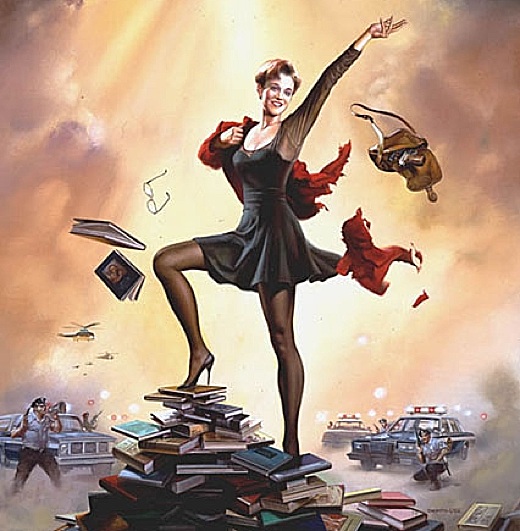

Image above:Detail of illustration of librarian triumphant protecting books from outside forces. From http://bookwormlibrarian.blogspot.com/2008/12/book-annotation.html

Generating electricity is not all that difficult in principle; people have been doing it since the 19th century. But generating power in large amounts, reliably, without both cheap energy inputs and secure availability of spare parts and investment capital for maintenance, poses an increasing challenge.

To be sure, here in the U.S. the lights are unlikely to go out all at once, and permanently, any time soon. The most likely scenario would see a gradual increase in rolling blackouts and other forms of power rationing, beginning in a few years, with some regions better off than others. After a while, unless governments and utilities could muster the needed effort, electricity might increasingly be seen as a luxury, even a curiosity. Reliable, ubiquitous, 24/7 power would become just a dim memory.

If the challenges noted above are not addressed, many nations, including the U.S., could be in such straits by the third decade of the century. In the best instance, nations would transition as much as possible to renewable power, maintaining a functioning national grid or network of local distribution systems, but supplying rationed power in smaller amounts than is the currently the case. Digitized data would still be retrievable part of the time, by some people.

In the worst instance, economic and social crises, wars, fuel shortages, and engineering problems would rebound upon one another, creating a snowballing pattern of systemic failures leading to permanent, total blackout.

It may seem inconceivable that it would ever come to that. After all, electrical power means so much to us that we assume that officials in charge will do whatever is necessary to keep the electrons flowing. But, as Jared Diamond documents in his book Collapse, elites don’t always do the sensible thing even when the alternative to rational action is universal calamity.

Altogether, the assumption that long-term loss of power is unthinkable just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. A permanent blackout scenario should exist as a contingency in our collective planning process.

Remember Websites?

Over the short term, if the power were to go out, loss of cultural knowledge would not be at the top of most people’s lists of concerns. They would worry about more mundane necessities like refrigeration, light, heat, and banking. It takes only a few moments of reflection (or an experience of living through a natural disaster) to appreciate how many of life’s daily necessities and niceties would be suddenly absent.

Of course, everyone did live without power until only a few generations ago, and hundreds of millions of people worldwide still manage in its absence. So it is certainly possible to carry on the essential aspects of human life sans functioning wall outlets. One could argue that, post-blackout, there would be a period of adaptation, during which people would reformulate society and simply get on with their business—living perhaps in a manner similar to their 19th century ancestors or the contemporary Amish.

The problem with that reassuring picture is that we have come to rely on electricity for so many things—and have so completely let go of knowledge, skills, and machinery that could enable us to live without electrical power—that the adaptive process might not go well. For the survivors, a 19th century way of life might not be attainable without decades or centuries spent re-acquiring knowledge and skills, and re-inventing machinery.

Imagine the scene, perhaps two decades from now. After years of gradually lengthening brownouts and blackouts, your town’s power has been down for days, and no one knows if or when it can be restored. No one is even sure if the blackout is statewide or nation-wide, because radio broadcasts have become more sporadic. The able members of your community band together to solve the mounting practical problems threatening your collective existence. You hold a meeting.

Someone brings up the problems of water delivery and wastewater treatment: the municipal facilities require power to supply these essential services. A woman in the back of the room speaks: “I once read about how you can purify water with a ceramic pot, some sand, and charcoal. It’s on a website….” Her voice trails off.

There are no more websites.

The conversation turns to food. Now that the supermarkets are closed (no functioning lights or cash registers) and emptied by looters, it’s obviously a good idea to encourage backyard and community gardening. But where should townspeople get their seeds? A middle-aged gentleman pipes up: “There’s this great mail-order seed company—just go online….” He suddenly looks confused and sits down.

“Online” is a world that no longer exists.

Is There Something We Should Be Doing?

There is a message here for leaders at all levels of government and business—obviously so for emergency response organizations. But I’ve singled out librarians in this essay because they may bear the gravest responsibility of all in preparing for the possible end of electric civilization.

Without widely available practical information, recovery from a final blackout would be difficult in the extreme. Therefore it is important that the kinds of information that people would need are identified, and that the information is preserved in such a way that it will be accessible under extreme circumstances, and to folks in widely scattered places.

Of course, librarians can never bear sole responsibility for cultural preservation; it takes a village, as Hillary Clinton once proclaimed in another context. Books are clearly essential to cultural survival, but they are just inert objects in the absence of people who can read them; we also need skills-based education to keep alive both the practical and the performing arts.

What good is a set of parts to the late Beethoven string quartets—arguably the greatest music our species has ever produced—if there’s no one around who can play the violin, viola, or cello well enough to make sense of them? And what good would a written description of horse-plowing do to a post-industrial farmer without the opportunity to learn hands-on from someone with experience?

Nevertheless, for librarians the message could not be clearer: Don’t let books die. It’s understandable that librarians spend much effort trying to keep up with the digital revolution in information storage and retrieval: their main duty is to serve their community as it is, not a community that existed decades ago or one that may exist decades hence. Yet the thought that they may be making the materials they are trying to preserve ever more vulnerable to loss should be cause for pause.

There is a task that needs doing: the conservation of essential cultural knowledge in non-digital form. This task will require the sorting and evaluation of information for its usefulness to cultural survival—triage, if you will—as well as its preservation. It may be unrealistic to expect librarians to take on this responsibility, given their existing mandate and lack of resources—but who else will do it? Librarians catalog, preserve, and make available accumulated cultural materials, especially those in written form. That’s their job. What profession is better suited to accept this charge?

The contemplation of electric civilization’s collapse can’t help but provoke philosophical musings. Perhaps cultural death is a necessary component of evolution—as is the death of individual organisms. In any case, no one can prevent culture from changing, and many aspects of our present culture arguably deserve to disappear (we each probably carry our own list around in our head of what kinds of music, advertising messages, and television shows we think the world could do without).

Assuming that humans survive the current century—by no means a sure thing—another culture will arise sooner or later to replace our current electric civilization. Its co-creators will inevitably use whatever skills and notions are at hand to cobble it together (just as the inhabitants of Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance drew upon cultural flotsam from the Roman Empire as well as influences from the Arab world), and it will gradually assume a life of its own. Still, we must ask: What cultural ingredients might we want to pass along to our descendants? What cultural achievements would we want to be remembered by?

Civilization has come at a price. Since the age of Sumer cities have been terrible for the environment, leading to deforestation, loss of topsoil, and reduced biodiversity. There have been human costs as well, in the forms of economic inequality (which hardly existed in pre-state societies) and loss of personal autonomy. These costs have grown to unprecedented levels with the advent of industrialism—civilization on crack—and have been borne not by civilization’s beneficiaries, but primarily by other species and people in poor nations and cultures.

But nearly all of us who are aware of these costs like to think of this bargain-with-the-devil as having some purpose greater than a temporary increase in creature comforts, safety, and security for a minority within society. The full-time division of labor that is the hallmark of civilization has made possible science—with its enlightening revelations about everything from human origins to the composition of the cosmos. The arts and philosophy have developed to degrees of sophistication and sublimity that escape the descriptive capacity of words.

Yet so much of what we have accomplished, especially in the last few decades, currently requires for its survival the perpetuation and growth of energy production and consumption infrastructure—which exact a continued, escalating environmental and human toll. At some point, this all has to stop, or at least wind down to some more sustainable scale of pillage.

But if it does, and in the process we lose the best of what we have achieved, will it all have been for nothing?

By Richard Heinberg on 7 October 2009 in Post Carbon Institute -

[IB Editor's Note: This is the concluding portion of the original article. To see the whole article click on the link above.]

Image above:Detail of illustration of librarian triumphant protecting books from outside forces. From http://bookwormlibrarian.blogspot.com/2008/12/book-annotation.html

Generating electricity is not all that difficult in principle; people have been doing it since the 19th century. But generating power in large amounts, reliably, without both cheap energy inputs and secure availability of spare parts and investment capital for maintenance, poses an increasing challenge.

To be sure, here in the U.S. the lights are unlikely to go out all at once, and permanently, any time soon. The most likely scenario would see a gradual increase in rolling blackouts and other forms of power rationing, beginning in a few years, with some regions better off than others. After a while, unless governments and utilities could muster the needed effort, electricity might increasingly be seen as a luxury, even a curiosity. Reliable, ubiquitous, 24/7 power would become just a dim memory.

If the challenges noted above are not addressed, many nations, including the U.S., could be in such straits by the third decade of the century. In the best instance, nations would transition as much as possible to renewable power, maintaining a functioning national grid or network of local distribution systems, but supplying rationed power in smaller amounts than is the currently the case. Digitized data would still be retrievable part of the time, by some people.

In the worst instance, economic and social crises, wars, fuel shortages, and engineering problems would rebound upon one another, creating a snowballing pattern of systemic failures leading to permanent, total blackout.

It may seem inconceivable that it would ever come to that. After all, electrical power means so much to us that we assume that officials in charge will do whatever is necessary to keep the electrons flowing. But, as Jared Diamond documents in his book Collapse, elites don’t always do the sensible thing even when the alternative to rational action is universal calamity.

Altogether, the assumption that long-term loss of power is unthinkable just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. A permanent blackout scenario should exist as a contingency in our collective planning process.

Remember Websites?

Over the short term, if the power were to go out, loss of cultural knowledge would not be at the top of most people’s lists of concerns. They would worry about more mundane necessities like refrigeration, light, heat, and banking. It takes only a few moments of reflection (or an experience of living through a natural disaster) to appreciate how many of life’s daily necessities and niceties would be suddenly absent.

Of course, everyone did live without power until only a few generations ago, and hundreds of millions of people worldwide still manage in its absence. So it is certainly possible to carry on the essential aspects of human life sans functioning wall outlets. One could argue that, post-blackout, there would be a period of adaptation, during which people would reformulate society and simply get on with their business—living perhaps in a manner similar to their 19th century ancestors or the contemporary Amish.

The problem with that reassuring picture is that we have come to rely on electricity for so many things—and have so completely let go of knowledge, skills, and machinery that could enable us to live without electrical power—that the adaptive process might not go well. For the survivors, a 19th century way of life might not be attainable without decades or centuries spent re-acquiring knowledge and skills, and re-inventing machinery.

Imagine the scene, perhaps two decades from now. After years of gradually lengthening brownouts and blackouts, your town’s power has been down for days, and no one knows if or when it can be restored. No one is even sure if the blackout is statewide or nation-wide, because radio broadcasts have become more sporadic. The able members of your community band together to solve the mounting practical problems threatening your collective existence. You hold a meeting.

Someone brings up the problems of water delivery and wastewater treatment: the municipal facilities require power to supply these essential services. A woman in the back of the room speaks: “I once read about how you can purify water with a ceramic pot, some sand, and charcoal. It’s on a website….” Her voice trails off.

There are no more websites.

The conversation turns to food. Now that the supermarkets are closed (no functioning lights or cash registers) and emptied by looters, it’s obviously a good idea to encourage backyard and community gardening. But where should townspeople get their seeds? A middle-aged gentleman pipes up: “There’s this great mail-order seed company—just go online….” He suddenly looks confused and sits down.

“Online” is a world that no longer exists.

Is There Something We Should Be Doing?

There is a message here for leaders at all levels of government and business—obviously so for emergency response organizations. But I’ve singled out librarians in this essay because they may bear the gravest responsibility of all in preparing for the possible end of electric civilization.

Without widely available practical information, recovery from a final blackout would be difficult in the extreme. Therefore it is important that the kinds of information that people would need are identified, and that the information is preserved in such a way that it will be accessible under extreme circumstances, and to folks in widely scattered places.

Of course, librarians can never bear sole responsibility for cultural preservation; it takes a village, as Hillary Clinton once proclaimed in another context. Books are clearly essential to cultural survival, but they are just inert objects in the absence of people who can read them; we also need skills-based education to keep alive both the practical and the performing arts.

What good is a set of parts to the late Beethoven string quartets—arguably the greatest music our species has ever produced—if there’s no one around who can play the violin, viola, or cello well enough to make sense of them? And what good would a written description of horse-plowing do to a post-industrial farmer without the opportunity to learn hands-on from someone with experience?

Nevertheless, for librarians the message could not be clearer: Don’t let books die. It’s understandable that librarians spend much effort trying to keep up with the digital revolution in information storage and retrieval: their main duty is to serve their community as it is, not a community that existed decades ago or one that may exist decades hence. Yet the thought that they may be making the materials they are trying to preserve ever more vulnerable to loss should be cause for pause.

There is a task that needs doing: the conservation of essential cultural knowledge in non-digital form. This task will require the sorting and evaluation of information for its usefulness to cultural survival—triage, if you will—as well as its preservation. It may be unrealistic to expect librarians to take on this responsibility, given their existing mandate and lack of resources—but who else will do it? Librarians catalog, preserve, and make available accumulated cultural materials, especially those in written form. That’s their job. What profession is better suited to accept this charge?

The contemplation of electric civilization’s collapse can’t help but provoke philosophical musings. Perhaps cultural death is a necessary component of evolution—as is the death of individual organisms. In any case, no one can prevent culture from changing, and many aspects of our present culture arguably deserve to disappear (we each probably carry our own list around in our head of what kinds of music, advertising messages, and television shows we think the world could do without).

Assuming that humans survive the current century—by no means a sure thing—another culture will arise sooner or later to replace our current electric civilization. Its co-creators will inevitably use whatever skills and notions are at hand to cobble it together (just as the inhabitants of Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance drew upon cultural flotsam from the Roman Empire as well as influences from the Arab world), and it will gradually assume a life of its own. Still, we must ask: What cultural ingredients might we want to pass along to our descendants? What cultural achievements would we want to be remembered by?

Civilization has come at a price. Since the age of Sumer cities have been terrible for the environment, leading to deforestation, loss of topsoil, and reduced biodiversity. There have been human costs as well, in the forms of economic inequality (which hardly existed in pre-state societies) and loss of personal autonomy. These costs have grown to unprecedented levels with the advent of industrialism—civilization on crack—and have been borne not by civilization’s beneficiaries, but primarily by other species and people in poor nations and cultures.

But nearly all of us who are aware of these costs like to think of this bargain-with-the-devil as having some purpose greater than a temporary increase in creature comforts, safety, and security for a minority within society. The full-time division of labor that is the hallmark of civilization has made possible science—with its enlightening revelations about everything from human origins to the composition of the cosmos. The arts and philosophy have developed to degrees of sophistication and sublimity that escape the descriptive capacity of words.

Yet so much of what we have accomplished, especially in the last few decades, currently requires for its survival the perpetuation and growth of energy production and consumption infrastructure—which exact a continued, escalating environmental and human toll. At some point, this all has to stop, or at least wind down to some more sustainable scale of pillage.

But if it does, and in the process we lose the best of what we have achieved, will it all have been for nothing?

No comments :

Post a Comment