SUBHEAD: Our lives when we were young, before the tides rose up and the power went out.

By Jay Ruben Dayrit on 13 December 2016 for Wired Magazine -

(https://www.wired.com/2016/12/jay-dayrit-hold-dear-the-lamp-light/)

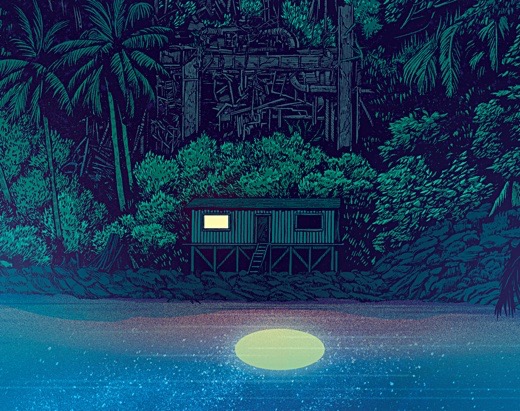

Image above: Illustration for story by Kevin Tong. From original article.

The year Jojo and I started eighth grade, the power plant officially cut electricity to two hours a day. We’d already been through years of brownouts, of flickering lights, blinking monitors, older ag drones without artificial neural networks rebooting in their stations and randomly launching to spray the fields again or overfeed the chickens.

So when Public Works & Electric issued a message to all our devices telling us about its irregular hours of operation, no one was surprised. The message was full of obfuscating language, but anyone with a tide chart could spot the correlation.

Anyone driving down the causeway to the airport, past the power plant, could see through its chain-link fence the turbines standing silent, tense as raised shoulders; the grounds swamped in seawater, the ebbing tide dragging out an iridescent Rorschach of petroleum.

A year before, the garbage dump had had to be relocated, a comparatively easier undertaking, after disposable diapers and plastic bottles began washing ashore on what was left of Ant Atoll, which had already lost its status as the premier diving destination for the Chinese.

The imminent blackouts stirred little protest from a population accustomed to making do. Aging water pipes had given rise to improvised cisterns situated at the eaves of every house.

Unreliable supply chains necessitated that we all have competence in maintaining our equipment. Mother Necessity knows how to weld with a zip tie, patch with duct tape, and repurpose a soda can.

Our father took Jojo and me, along with a box of winged beans, bitter melon, and a dozen eggs, over to Bauer’s Hardware. He and Friedrich Bauer had been tennis buddies before the tractor accident. Back then the hospital was even less equipped to handle emergencies, and Friedrich died before he could be medevaced to Guam.

The produce was for Yessica, who had taken over the hardware store. In return, she discounted the Coleman lantern and three bags of charcoal, throwing in a 10-pack of Diamond Strike matches for free. She marveled at how tall Jojo and I had grown but confessed she still couldn’t tell us apart.

Our father placed his hand on my brother’s shoulder. “Joseph here is interested in civil engineering. Alejandro, medicine,” he said, as if we’d come up with these ideas on our own. “They’ll be going to Central Pacific next year.”

Yessica’s smile couldn’t mask the flutter of melancholy in her eyes. Friedrich had graduated from there. Anyone from Micronesia who went to Hawaii for school attended Central Pacific High School.

Its boarding program had gained a reputation for welcoming students from other islands like the Marshalls and Pingelap, lower-lying atolls that had all but disappeared.

When the Office of Insular Affairs renewed the Compact of Free Association for the second time, the penultimate wave of Micronesians arrived in Hawaii, seeking access to better education, jobs, and health care, especially for the blood-borne cancers and autoimmune disorders that were still persistent three generations after nuclear testing.

With that influx into Hawaii came a resurgence of housing and job discrimination, racial tension, and violence.

We’d heard that the faculty at Central Pacific encouraged empathy between Hawaiians and Micronesians, highlighting cultural commonalities like celestial navigation and traditional dances. But the fact that there wasn’t a lot of bullying, we knew, had more to do with safety in numbers.

A few friends who were home for the summer had reassured Jojo and me we’d be OK, because we were Filipinos who sounded American. With our straight hair and lighter skin, we could pass. Still, we were told to learn how to block a punch.

Better yet, learn how to throw one. Jojo and I practiced in our bedroom, aiming for the shoulder, where the sleeves of our T-shirts concealed the bruises that might betray to our parents how we were preparing for high school.

After returning from the hardware store, Jojo and I helped our mother empty the refrigerator, defrost the freezer, and scrape the barbecue grill. She marinated all the meat in soy sauce, calamansi juice, and garlic.

Our father threw pork chops and steaks on the grill, but we all felt decadent eating so much red meat. And our mother worried about gout, to which Filipinos were predisposed. She rattled off the names of five of our uncles back in Pampanga as evidence.

So we gave the excess thawed meat to our neighbors. The house down the road was owned by the hospital and, over the years, was home to a string of American doctors offsetting their excessive student loans by practicing in underserved countries.

Dr. Westlake and Dr. Phan, two female residents who enjoyed throwing cocktail parties, happily accepted the food. Up the road, the McGuires, who were from New Zealand, insisted our generosity was too much. They eventually relented, because our mother refused to take no for an answer.

They had a son our age, Derek, whose company Jojo and I didn’t particularly enjoy. Whenever there was electricity, he’d run through the break in the gardenia hedge that separated our properties and challenge us to new games his parents let him download freely.

He knew our cross-platform visors were a generation older and glitchier, that invariably we’d lose. “I win, again!” Derek would cheer behind his visor.

Jojo and I would remove ours and exchange glances, consoled in knowing an only child needs to feel good about something.

Surely our parents found the rationed power supply inconvenient: driving to the fish market every day, cooking rice over an open flame, taking the clothes off the line so they wouldn’t reek of lighter fluid. But Jojo and I recall the blackouts fondly.

We remember our whole neighborhood, just a scattering of houses along a gravel road, smelling of barbecued chicken and fish. We remember eating grilled corn and eggplant with bagoong.

We remember Auntie Betina arriving for dinner with a Folger’s coffee can of chocolate chip cookies she’d somehow managed to bake in the brief window of electricity that day.

We remember pink sunsets stretching across the sky, families in their backyards, laughter carried by the breeze in the waning sunlight. We remember the Coleman lantern, how its mantle, little more than an ashen net the shape of an infant’s sock, cast a steady light against the back of the house. Our shadows, sharp as paper cutouts, slid across the wall as we helped ourselves to seconds.

We took leisurely family walks after dinner. “An evening constitutional,” as our father called it, evoking an era when people said things like that. No porch lights to mark our path, not even the bluish glow of our devices, which we stowed to conserve battery power while the networks were down. The moon illuminated the road well enough.

We stopped to talk to other people strolling after dinner, mostly Filipinos who lived in the neighborhood.

The men crossed their arms atop full bellies, discussing local politics and the precarious economy. The women gossiped about recent expats from the Philippines—who was single, who wasn’t but acted as if they were.

Back home, by the light of the Coleman, our father, who could not be bothered with fiction, read biographies. Our mother read pulpy detective novels. Since the blackouts, she and her friends had started a book exchange that quickly extended beyond the Filipinas to the Americans, the Australians, even the Japanese.

Jojo picked up The Serrano Trilogy again, which he’d attempted to read several times in the past but had always abandoned for his visor and its less challenging entertainment.

Never much of a reader myself, I opted to flip through National Geographic, unfolding maps of faraway places, studying borders that would have to be redrawn sooner than any of us expected.

Before our predicament was overshadowed by the mass evacuations of Shanghai, Amsterdam, and America’s coastal cities to higher ground; before the famine conflicts spilled over from Africa to the Middle East; before Micronesia’s depleted population eventually triggered its economic collapse and the expats, our parents included, retreated to inner regions of their own countries; before all those major catastrophes, we had the blackout years.

Now I hold dear the lamplight and the rustle of paper at our fingertips, our parents reading passages aloud, being together in the darkness.

That first year, Jojo and I came to believe we could easily live without electricity.

But we were children and our beliefs unrealistic, like the plan to relocate the power plant before it and everything else succumbed to the sea.

.

By Jay Ruben Dayrit on 13 December 2016 for Wired Magazine -

(https://www.wired.com/2016/12/jay-dayrit-hold-dear-the-lamp-light/)

Image above: Illustration for story by Kevin Tong. From original article.

The year Jojo and I started eighth grade, the power plant officially cut electricity to two hours a day. We’d already been through years of brownouts, of flickering lights, blinking monitors, older ag drones without artificial neural networks rebooting in their stations and randomly launching to spray the fields again or overfeed the chickens.

So when Public Works & Electric issued a message to all our devices telling us about its irregular hours of operation, no one was surprised. The message was full of obfuscating language, but anyone with a tide chart could spot the correlation.

Anyone driving down the causeway to the airport, past the power plant, could see through its chain-link fence the turbines standing silent, tense as raised shoulders; the grounds swamped in seawater, the ebbing tide dragging out an iridescent Rorschach of petroleum.

A year before, the garbage dump had had to be relocated, a comparatively easier undertaking, after disposable diapers and plastic bottles began washing ashore on what was left of Ant Atoll, which had already lost its status as the premier diving destination for the Chinese.

The imminent blackouts stirred little protest from a population accustomed to making do. Aging water pipes had given rise to improvised cisterns situated at the eaves of every house.

Unreliable supply chains necessitated that we all have competence in maintaining our equipment. Mother Necessity knows how to weld with a zip tie, patch with duct tape, and repurpose a soda can.

Our father took Jojo and me, along with a box of winged beans, bitter melon, and a dozen eggs, over to Bauer’s Hardware. He and Friedrich Bauer had been tennis buddies before the tractor accident. Back then the hospital was even less equipped to handle emergencies, and Friedrich died before he could be medevaced to Guam.

The produce was for Yessica, who had taken over the hardware store. In return, she discounted the Coleman lantern and three bags of charcoal, throwing in a 10-pack of Diamond Strike matches for free. She marveled at how tall Jojo and I had grown but confessed she still couldn’t tell us apart.

Our father placed his hand on my brother’s shoulder. “Joseph here is interested in civil engineering. Alejandro, medicine,” he said, as if we’d come up with these ideas on our own. “They’ll be going to Central Pacific next year.”

Yessica’s smile couldn’t mask the flutter of melancholy in her eyes. Friedrich had graduated from there. Anyone from Micronesia who went to Hawaii for school attended Central Pacific High School.

Its boarding program had gained a reputation for welcoming students from other islands like the Marshalls and Pingelap, lower-lying atolls that had all but disappeared.

When the Office of Insular Affairs renewed the Compact of Free Association for the second time, the penultimate wave of Micronesians arrived in Hawaii, seeking access to better education, jobs, and health care, especially for the blood-borne cancers and autoimmune disorders that were still persistent three generations after nuclear testing.

With that influx into Hawaii came a resurgence of housing and job discrimination, racial tension, and violence.

We’d heard that the faculty at Central Pacific encouraged empathy between Hawaiians and Micronesians, highlighting cultural commonalities like celestial navigation and traditional dances. But the fact that there wasn’t a lot of bullying, we knew, had more to do with safety in numbers.

A few friends who were home for the summer had reassured Jojo and me we’d be OK, because we were Filipinos who sounded American. With our straight hair and lighter skin, we could pass. Still, we were told to learn how to block a punch.

Better yet, learn how to throw one. Jojo and I practiced in our bedroom, aiming for the shoulder, where the sleeves of our T-shirts concealed the bruises that might betray to our parents how we were preparing for high school.

After returning from the hardware store, Jojo and I helped our mother empty the refrigerator, defrost the freezer, and scrape the barbecue grill. She marinated all the meat in soy sauce, calamansi juice, and garlic.

Our father threw pork chops and steaks on the grill, but we all felt decadent eating so much red meat. And our mother worried about gout, to which Filipinos were predisposed. She rattled off the names of five of our uncles back in Pampanga as evidence.

So we gave the excess thawed meat to our neighbors. The house down the road was owned by the hospital and, over the years, was home to a string of American doctors offsetting their excessive student loans by practicing in underserved countries.

Dr. Westlake and Dr. Phan, two female residents who enjoyed throwing cocktail parties, happily accepted the food. Up the road, the McGuires, who were from New Zealand, insisted our generosity was too much. They eventually relented, because our mother refused to take no for an answer.

They had a son our age, Derek, whose company Jojo and I didn’t particularly enjoy. Whenever there was electricity, he’d run through the break in the gardenia hedge that separated our properties and challenge us to new games his parents let him download freely.

He knew our cross-platform visors were a generation older and glitchier, that invariably we’d lose. “I win, again!” Derek would cheer behind his visor.

Jojo and I would remove ours and exchange glances, consoled in knowing an only child needs to feel good about something.

Surely our parents found the rationed power supply inconvenient: driving to the fish market every day, cooking rice over an open flame, taking the clothes off the line so they wouldn’t reek of lighter fluid. But Jojo and I recall the blackouts fondly.

We remember our whole neighborhood, just a scattering of houses along a gravel road, smelling of barbecued chicken and fish. We remember eating grilled corn and eggplant with bagoong.

We remember Auntie Betina arriving for dinner with a Folger’s coffee can of chocolate chip cookies she’d somehow managed to bake in the brief window of electricity that day.

We remember pink sunsets stretching across the sky, families in their backyards, laughter carried by the breeze in the waning sunlight. We remember the Coleman lantern, how its mantle, little more than an ashen net the shape of an infant’s sock, cast a steady light against the back of the house. Our shadows, sharp as paper cutouts, slid across the wall as we helped ourselves to seconds.

We took leisurely family walks after dinner. “An evening constitutional,” as our father called it, evoking an era when people said things like that. No porch lights to mark our path, not even the bluish glow of our devices, which we stowed to conserve battery power while the networks were down. The moon illuminated the road well enough.

We stopped to talk to other people strolling after dinner, mostly Filipinos who lived in the neighborhood.

The men crossed their arms atop full bellies, discussing local politics and the precarious economy. The women gossiped about recent expats from the Philippines—who was single, who wasn’t but acted as if they were.

Back home, by the light of the Coleman, our father, who could not be bothered with fiction, read biographies. Our mother read pulpy detective novels. Since the blackouts, she and her friends had started a book exchange that quickly extended beyond the Filipinas to the Americans, the Australians, even the Japanese.

Jojo picked up The Serrano Trilogy again, which he’d attempted to read several times in the past but had always abandoned for his visor and its less challenging entertainment.

Never much of a reader myself, I opted to flip through National Geographic, unfolding maps of faraway places, studying borders that would have to be redrawn sooner than any of us expected.

Before our predicament was overshadowed by the mass evacuations of Shanghai, Amsterdam, and America’s coastal cities to higher ground; before the famine conflicts spilled over from Africa to the Middle East; before Micronesia’s depleted population eventually triggered its economic collapse and the expats, our parents included, retreated to inner regions of their own countries; before all those major catastrophes, we had the blackout years.

Now I hold dear the lamplight and the rustle of paper at our fingertips, our parents reading passages aloud, being together in the darkness.

That first year, Jojo and I came to believe we could easily live without electricity.

But we were children and our beliefs unrealistic, like the plan to relocate the power plant before it and everything else succumbed to the sea.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment