SUBHEAD: His actions are accelerating climate destruction while his inaction on the effects endangers us all.

By Keith Kozloff on 22 April 2017 for Resilience -

(http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-04-22/president-trumps-climate-inaction-sells-future-short/)

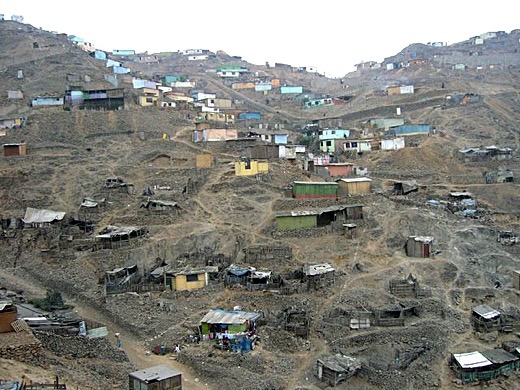

Image above: Photo of low-income area of Lima, Peru in devastated ecosystem. Photo by Sustainable Sanitation Alliance. From original article.

This weekend, thousands of scientists and concerned citizens from across the globe will take to the streets to defend the vital role science plays in our health, safety, economies, and governments.

Coinciding with Earth Day (April 22), this international March for Science will take place less than a month after President Trump signed an executive order aiming to decimate his predecessor’s scientifically sound policies on climate change.

In the cacophony of bad climate stories recently, you’d be forgiven for missing the news that one casualty of Trump’s order was the social cost of carbon (SCC), a measure that’s been called “the most important number you’ve never heard of.”

The SCC captures the estimated costs of climate disruption from things like sea-level rise, storms, fires, crop failures and rising death rates. Before Trump’s order, federal agencies were required to consider these costs when designing relevant policies and programs.

While it is difficult to put an exact price tag on future costs from a disrupted climate, a federal court affirmed last August that the current SCC estimate ($36 per ton of CO2 emitted) is based on sound science.

Mr. Trump’s executive order would effectively reduce that figure to close to zero. This will hamstring US efforts to protect future generations from climate disruption.

To understand why, consider an analogy. Let’s say that in 2018 scientists discover an asteroid as big as the one that killed off the dinosaurs—and it’s headed our way. NASA says there is a 25% chance the asteroid will collide with the Earth in 30 years’ time. Fortunately, a new technology could gradually shift the asteroid’s trajectory if launched in time.

It’s expensive: the required investment would be an order of magnitude larger than spending on our moon program. And the effort would need to begin immediately: If the US waits to be sure that the asteroid will hit the Earth, it would be too late to nudge the asteroid from its path of destruction.

To decide what to do, government economists conduct a conventional cost/benefit analysis. The cost side of the equation consists of developing and deploying the asteroid-deflecting spacecraft.

Benefits consist of estimated damages to human life, property, etc. that would be avoided if the project moves forward. Economists count only benefits to the US, discount them heavily because they accrue far in the future, and adjust them for the 25% probability of impact.

Based on this analysis, politicians—who are always reluctant to pay for benefits that accrue after they leave office–decide not to act. As luck would have it, the asteroid slams into the Earth in 2048.

Today, we face a similar choice regarding global climate change—another problem that requires near-term investments to prevent potentially unthinkable long-term costs. Cost/benefit analysis can be a useful tool, among others, for decision-making on climate policy. But President Trump’s executive order calls for federal agencies to apply the same constricted approach used by government economists in the asteroid analogy.

To support sound climate policies, the SCC should continue to be used, refined, and updated as evidence accumulates on climate-related damages.

Maintaining a robust SCC would help to ensure we do not discount the lives and well-being of future generations, who cannot argue the case themselves.

If they could, they would likely argue that even a low risk of incurring unacceptable costs warrants action. This is the same logic that guides expenditures around other threats to our national security, such as international terrorism.

As we prepare to march this weekend, it’s critical that we realize climate disruption is our asteroid. We do not know its exact trajectory, so we can’t be sure our interventions are needed to prevent disaster.

Future generations, looking back, may forgive us if it turns out we acted unnecessarily. If we instead fail to act when we should have, our children’s children will be less charitable in their assessment.

This commentary was produced in collaboration with the Island Press Urban Resilience Project, with support from The Kresge Foundation and The JPB Foundation.

.

By Keith Kozloff on 22 April 2017 for Resilience -

(http://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-04-22/president-trumps-climate-inaction-sells-future-short/)

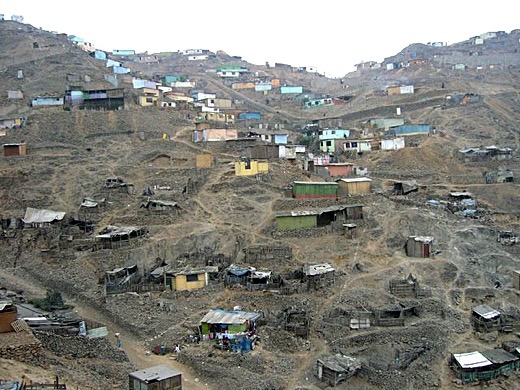

Image above: Photo of low-income area of Lima, Peru in devastated ecosystem. Photo by Sustainable Sanitation Alliance. From original article.

This weekend, thousands of scientists and concerned citizens from across the globe will take to the streets to defend the vital role science plays in our health, safety, economies, and governments.

Coinciding with Earth Day (April 22), this international March for Science will take place less than a month after President Trump signed an executive order aiming to decimate his predecessor’s scientifically sound policies on climate change.

In the cacophony of bad climate stories recently, you’d be forgiven for missing the news that one casualty of Trump’s order was the social cost of carbon (SCC), a measure that’s been called “the most important number you’ve never heard of.”

The SCC captures the estimated costs of climate disruption from things like sea-level rise, storms, fires, crop failures and rising death rates. Before Trump’s order, federal agencies were required to consider these costs when designing relevant policies and programs.

While it is difficult to put an exact price tag on future costs from a disrupted climate, a federal court affirmed last August that the current SCC estimate ($36 per ton of CO2 emitted) is based on sound science.

Mr. Trump’s executive order would effectively reduce that figure to close to zero. This will hamstring US efforts to protect future generations from climate disruption.

To understand why, consider an analogy. Let’s say that in 2018 scientists discover an asteroid as big as the one that killed off the dinosaurs—and it’s headed our way. NASA says there is a 25% chance the asteroid will collide with the Earth in 30 years’ time. Fortunately, a new technology could gradually shift the asteroid’s trajectory if launched in time.

It’s expensive: the required investment would be an order of magnitude larger than spending on our moon program. And the effort would need to begin immediately: If the US waits to be sure that the asteroid will hit the Earth, it would be too late to nudge the asteroid from its path of destruction.

To decide what to do, government economists conduct a conventional cost/benefit analysis. The cost side of the equation consists of developing and deploying the asteroid-deflecting spacecraft.

Benefits consist of estimated damages to human life, property, etc. that would be avoided if the project moves forward. Economists count only benefits to the US, discount them heavily because they accrue far in the future, and adjust them for the 25% probability of impact.

Based on this analysis, politicians—who are always reluctant to pay for benefits that accrue after they leave office–decide not to act. As luck would have it, the asteroid slams into the Earth in 2048.

Today, we face a similar choice regarding global climate change—another problem that requires near-term investments to prevent potentially unthinkable long-term costs. Cost/benefit analysis can be a useful tool, among others, for decision-making on climate policy. But President Trump’s executive order calls for federal agencies to apply the same constricted approach used by government economists in the asteroid analogy.

To support sound climate policies, the SCC should continue to be used, refined, and updated as evidence accumulates on climate-related damages.

Maintaining a robust SCC would help to ensure we do not discount the lives and well-being of future generations, who cannot argue the case themselves.

If they could, they would likely argue that even a low risk of incurring unacceptable costs warrants action. This is the same logic that guides expenditures around other threats to our national security, such as international terrorism.

As we prepare to march this weekend, it’s critical that we realize climate disruption is our asteroid. We do not know its exact trajectory, so we can’t be sure our interventions are needed to prevent disaster.

Future generations, looking back, may forgive us if it turns out we acted unnecessarily. If we instead fail to act when we should have, our children’s children will be less charitable in their assessment.

This commentary was produced in collaboration with the Island Press Urban Resilience Project, with support from The Kresge Foundation and The JPB Foundation.

.

No comments :

Post a Comment