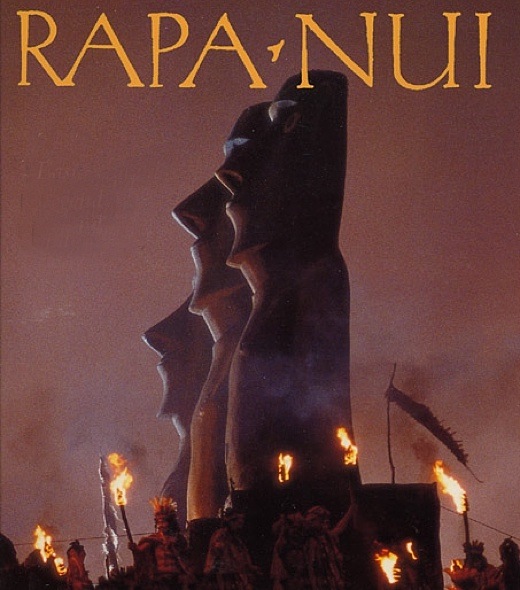

Image above: Poster for "Rapa Nui: The Easter Island Legend on Film" by Kevin Reynolds and Tim Rose Price in 1994.

By Ralph Faggotter on 8 April 2010 in The Oil Drum -

(http://anz.theoildrum.com/node/6333)

This is a case study in which you are invited to answer the question, “What did the Easter Islander who cut down the last palm tree say while he was doing it?”

Image above: Poster for "Rapa Nui: The Easter Island Legend on Film" by Kevin Reynolds and Tim Rose Price in 1994.

By Ralph Faggotter on 8 April 2010 in The Oil Drum -

(http://anz.theoildrum.com/node/6333)

This is a case study in which you are invited to answer the question, “What did the Easter Islander who cut down the last palm tree say while he was doing it?” For a several years, I have been intrigued by this question which Jared Diamond asks us to consider in his book ‘Collapse’.

In fact, the question can be asked more broadly: “What were the thought processes and discussions amongst the inhabitants of Easter Island leading up to the removal of the last remnants of forest?” This could be seen, perhaps, as a hypothetical exploration, rooted in a real historical event, of “the psychology of resource depletion denial.”

I can’t help feeling that this is highly relevant to us today where the world seems shrunk to the size of a small island in the vast ocean of space. How could the islanders so knowingly have destroyed the life-blood of their island and their own future? How do you imagine the Easter Islanders behaved in those last few years before the last tree was felled?

For some of the rationalizations, we probably don’t need to look any further than our local talkback radio, the proceedings of the Copenhagen convention or the comments section on any mainstream media opinion piece about Peak Oil or Climate Change, but there would certainly have been powerful idiosyncratic religious beliefs at play too.

Setting the Scene:

Easter Island is a small triangular island of 66 sq miles in the sub-tropical South East Pacific Ocean over 1000 miles from anywhere and consisting of three linked extinct volcanoes.

It was first settled by Polynesians who migrated there from the nearest Pacific Islands to the west, sometime between 400 AD and 900 AD.

When they arrived bringing their traditional Polynesian vegetables the island was covered in a variety of large and smaller species of trees and in particular a very large species of palm tree with edible nuts and a wide girth, seals and many species of sea birds which nested there free from predators (incidentally rats which played an important role in the deforestation by eating seeds and nuts).

There were no permanent creeks and the soil and climate were relatively unfavourable compared with many other Pacific Islands for a number of reasons, but at first it must have seemed wonderfully bountiful.

The population grew and 12 tribes became established, with the island divided up like a pizza in the traditional Polynesian way (ahupuaa in Hawaii). Most significantly, there was no one supreme chief--instead each tribe vied for status with one other. For the most part, this was probably fairly harmonious with considerable cooperation between the tribes probably mediated by a counsel of the chiefs of the 12 tribes such as we see elsewhere but with intermittent power and territorial struggles (this absence of a single controlling chief may have played a big part in the disasters which followed).

The settlers brought with them their traditional Polynesian religious beliefs regarding deification of ancestors transmogrified into gods of fertility and bounty personified in the shape of stone statues--carved, transported and placed on impressive stone platforms near the beach around the coast in each tribe’s territory.

Elsewhere in Polynesia though, the statues tend to be small. Presumably, as the statues represented the power of the chiefs and their link to the supernatural and hence the future prosperity of the tribe, there developed intense competition between the tribes to see who could have the most statues and the largest statues and hence the most prestige and glory. The key village of each tribe was located near to the beach and the statues were arranged in a row between the village and the sea. I had always imagined that they faced outwards towards the sea but recently learned that they actually faced inwards towards the village.

Nearly all of the statues came from one quarry of ideal stone near the middle of the island. The statues had to be carved out of the rock, using harder stone tools, and then transported down to the coast and then somehow erected on the platforms. (The large reddish cylindrical hats which can be seen on some statues came from another quarry.)

This transportation was an extraordinary feat and could only be performed using vast numbers of wooden rollers, sledges and levers, not to mention the incredible number of man hours per statue. The capacity of the island to provide a relatively easy living (what we would call the EROEI) so as to free up so many workers for seemingly non-productive activity must have been considerable.

But over the centuries, this non-productive use of the forests, combined with increased need for timber due to population growth, would have gradually resulted in progressive deforestation, loss of habitat for a variety of edible plants, birds and animals, loss of protection from sun and wind, loss of fire wood and erosion of soil.

Natural reseeding would have been inhibited by a plentiful supply of seed-eating rats which had few natural enemies on the island (probably only humans and birds of prey).

The phenomenon of ‘creeping normalcy’ may have prevented anyone from noticing this decline for a few centuries - especially as the early statues were comparatively small and would have consumed the forests at a relatively modest rate.

But as the forests shrunk in area and the annual percentage rate of depletion steadily increased, at some point, someone must have realized that the situation was not sustainable and said as much. The island is not that big and what was happening at one end would have been common knowledge at the other end.

By around the year 1600, the last tree was chopped down and there were no more until they were reintroduced by Europeans many years later.

Some time before the last tree was cut down- perhaps this was done in a moment of spite, desperation, anger or vengeance - the society collapsed into mass starvation, war and cannibalism.

Image above: Detail of poster for "Rapa-Nui", 1994, a dramatization of the end days of Easter Island, produced by Kevin Costner. From (http://www.impawards.com/1994/rapa_nui.html)

Image above: Detail of poster for "Rapa-Nui", 1994, a dramatization of the end days of Easter Island, produced by Kevin Costner. From (http://www.impawards.com/1994/rapa_nui.html)

What might have happened in the lead up?

One can imagine between 1400 and 1500, some of the people muttering about the loss of forest and predicting that “..at the current rate it will all be gone in a generation or two.”

How did the chiefs react to this prediction ? Did they have a ‘Forest Change’ summit? Was it on the agenda of one of their regular meetings and at what percentage of depletion from the original virgin forest did this occur? 50%? 70%? 90%?

Where the first whistleblowers listened to or ridiculed or punished? Perhaps at first they were ridiculed as eccentrics then if they persisted. Perhaps they were seen as a genuine threat to the establishment and eaten as human sacrifice (with the priests getting first pick of the good bits) as was the order of the day. This would have kept the doomsters quiet for a while though many may have continued to secretly harbour fears for the long-term sustainability of the forest.

There would have been powerful forces opposed to the expression of such heretical ideas. The power of the chiefs, the priestly caste and the gods/ancestors was integrated both practically and theologically (as we see in most societies).

There is a kind of unassailable philosophy which says that the hereditary rights and powers of the chiefs are the manifestation on Earth of the Will of the Gods. The ancestors of the chiefs (i.e. dead chiefs) take on god-like powers. The role of the gods is to ensure the ongoing health, fertility and prosperity of the people and the ongoing bountifulness of the land and sea. The priests interpret ‘The Will of the Gods’ which somehow always favours the centralisation of power with the chiefs and the priests.

The statue of the chief becomes one of the key physical manifestations of this power.

This all works very well with the people and the king’s security service remaining loyal and willing to provide tithes of goods and services to the king and his retinue in return for their ongoing guaranteed prosperity.

But this kind of system can easily initiate a competitive positive feedback loop in which each chief attempts to outdo his rival chiefs in creating the biggest and the best statue in his own honour (the gods have confirmed in each case that this is their wish).

Unfortunately the gods can be fickle too and sometimes, in spite of all the standard observances, prayers, ritual, human sacrifices and statue building, the tribes will go through a bad patch in which the fish disappear, the sea birds don’t nest, the rain doesn’t arrive, pests or diseases damage the root crops or other mysterious and inexplicable bad things (like cyclones or tsunami) happen.

When this happens the loyalty of the people and their faith in the system can be sorely tested so that the chief will need to respond to the crisis in some way. One way is to accuse some already unpopular people of witchcraft, blasphemy, giving out bad vibes/negative energy etc to deliberately cause the bad weather events - in other words a scapegoat. These offenders might also coincidentally be the very persons who had been advocating the building of smaller statures in order to avoid cutting down so many trees.

Another response apart from ruthlessly suppressing all dissent is to logically argue that the gods must be displeased because the statues aren’t big enough and a nervous chief, worried about his shrinking powerbase will commission the production of an even bigger statue just to confirm his piety and majesty.

In spite of all this the Establishment themselves must at some point have started to notice the bleeding obvious, namely that the forest was nearly gone and that they would have to discuss how best to avoid losing the remaining bits of forest.

So what happened next? Why didn’t a workable plan emerge and get implemented? If it did what went wrong? Can we blame it all on tribalism and ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’? We know the final outcome, but what was the path to that outcome and are we treading that same path again?

It would have been wonderful to have had a written historical record of the details but in its absence, it what do you imagine happened?

.

No comments :

Post a Comment