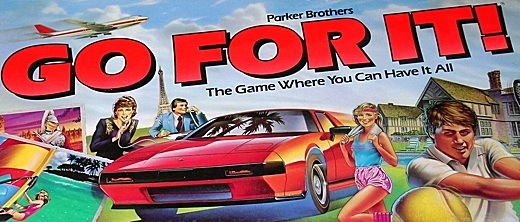

Image above: Box of game "Go For It!" by Parker Brothers "the game where you can have it all".

From http://www.brandedinthe80s.com/index.php?post_id=225373

Image above: Box of game "Go For It!" by Parker Brothers "the game where you can have it all".

From http://www.brandedinthe80s.com/index.php?post_id=225373

Paul Joegriner hasn't worked since March 2008, when he was laid off from his $200,000-a-year job as chief executive officer of a small bank. But you wouldn't know it by appearances.

His wife, Marzena, shuttles their two young children to private school every morning. The family recently vacationed in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and likes to dine on Porterhouse steaks. Since losing his job, Mr. Joegriner, 44 years old, has had several offers. He's turned each down in hopes of landing a position comparable to what he held before.

The family's lifestyle over the past year and a half has been propped up by a $200,000 severance package and another $100,000 in savings -- funds the family has burned through rapidly. By Mr. Joegriner's own calculations, the family will be out of money in six months if he doesn't find work.

"It will be D-Day," he says. "But on the outside, no one has any idea that we're in trouble."

Mr. Joegriner is a member of what might be called the severance economy -- unemployed Americans who use severance pay and savings to maintain their lifestyles. Many lost their jobs in 2007 and 2008, and thought they'd soon find work. Now, they're getting desperate. Last week, lawmakers passed a bill extending unemployment benefits up to 20 weeks. Unemployment benefits, which typically last about 26 weeks, were expected to run out for 1.3 million people by the end of the year, according to the National Employment Law Project.

All of this is happening as the long-term jobless rate hits its highest point on record. More than a third of those who are out of work have been looking for more than six months, making this category of unemployed the biggest since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking it in 1948.

Overall, companies have been eliminating or trimming severance packages. For those who do receive severance, the median pay allotted is 12.5 weeks' salary, down from 21.8 weeks a decade ago, according to outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

But this downturn has brought heavy layoffs to the financial and auto industries, two places where generous exit packages remain more common. The dramatic changes in such sectors mean that many of the eliminated jobs will never come back. Some workers may suffer a permanent hit to their standard of living.

Those affected often have trouble accepting their diminished prospects. Hefty severance packages, while intended as a safety net, can lull the unemployed into a false sense of security. Some people continue spending as before.

"There is an end date when that severance is going to run out," says Ellen Turf, chief executive of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors. "At that point, the only life preserver is unemployment or getting another job....It's an awful situation."

When Michelle Patterson was laid off as an executive director of marketing for a publishing company in January, she figured she could subsist comfortably, at least for a while, on the $20,000 she had reserved from her savings and severance combined. She continued to eat out regularly and made daily Starbucks runs.

"It made me feel like I was still at work," says the 41-year-old resident of Newark, N.J. She spent as much as $250 a week on networking meals and drinks with contacts. Some days, she scheduled up to four coffee meetings a day, picking up the tab most of the time. She also spent $30 a month for pedicures and $150 on her hair.

The reckoning came in August, when she examined her finances. Her condo had been on the market for six months but she'd yet to receive a single offer. Her severance and savings were nearly gone.

She finally cut her spending. She doesn't dine out anymore. Gone are the fancy salon visits; Ms. Patterson sips Starbucks just once a week. She downgraded her cable TV to basic channels, saving $8 a month.

Ms. Patterson sometimes wishes she had cut her spending earlier. But the money spent networking and socializing, she says, has "helped [me] keep sane." Like many of the long-term unemployed, she surfs sites like Monster.com and is a "serial résumé sender" -- emailing at least 10 résumés a day. Still, "I keep running into dead ends," she says.

Coming to terms with the new job math hasn't been easy. Ms. Patterson's old salary was $140,000 a year. Now she is targeting jobs paying about half that. She recently turned down a per-diem arrangement earning $250 a week, or a mere $13,000 a year, selling education software.

After working for more than a decade in New York ad shops, Chuck Hipsher moved to Detroit in 2005. He took a position at the Campbell-Ewald agency, where he helped launch the Chevrolet Silverado campaign. Raised riding in the back of his grandfather's Chevy pickup in Iowa, Mr. Hipsher, 50, says he was "elated" at the opportunity.

He met his wife at the ad agency, and the two had a $40,000 wedding. Kelly Hipsher, 32, was laid off in October 2007 and found out she was pregnant in February 2008. A week later, Mr. Hipsher's pink slip followed. Two months after that, the out-of-work couple moved to Greenville, S.C., to be closer to family and get a fresh start. Together, they had received about $60,000 in severance. "Now we have $600 to our name," says Mr. Hipsher.

Although their rent was cheaper, Mr. Hipsher says the family continued to spend like before. They moved with three cars -- two BMWs and a Chevy Silverado. They continued to buy cases of $36-a-bottle wine. They spent $250 a month on a cleaning lady, and Mr. Hipsher dropped $50 a week on flowers for his wife. The couple still dined out regularly.

"We were stupid," he says. "You become accustomed to a certain lifestyle. When your world changes and things dictate that you change, you're pretty stubborn to give things up."

He sold the BMWs and voluntarily turned in his beloved Silverado to avoid the repo man. "It was heartbreaking," he says. He replaced the fancy wheels with a Chrysler minivan.

Before the layoffs, the Hipshers had no debt. Today, they owe about $70,000 -- including money borrowed from family members and $31,000 in credit-card debt. To hold off the collection companies that call daily, Mr. Hipsher says he is doing his best but is also considering filing for personal bankruptcy.

After a stint selling new and used BMWs on a lot in Greenville, Mr. Hipsher recently began consulting for free for a small marketing firm, "to stay busy."

In September, a Web solutions company hired him as a marketing director. Between salary and commission, he thought he could match half his old income. But so far, he says he's only received about $1,220. Tight for cash recently, he pawned his wife's $12,000 wedding ring for a $2,000 loan. He has until Dec. 28 to pay back the principal, plus $500 in interest -- or else he forfeits the ring.

Looking back, he kicks himself for failing to enforce financial discipline right after losing his job in Detroit. "That precious nest egg is gone," he says.

Mr. Joegriner began his career in banking more than 20 years ago, starting out as a part-time teller in Chevy Chase, Md. Even though he was still in college, his goal was to be a CEO. He took night classes to enhance his knowledge of banking.

Mr. Joegriner says he never craved a lavish lifestyle. When the first of their two children was born in 2000, his wife left her $50,000-year-job as a paralegal.The family settled in Silver Spring rather than pricier communities nearby. Instead of tailored suits for $1,000, he bought off-the-rack styles for $300. Mr. Joegriner purchased a Mercedes five years ago, but at auction.

After losing his job, Mr. Joegriner expected to land on his feet within six months, he says. In that time, he turned down three job offers to be a chief financial officer, either because he didn't like the salary or the description of duties, and thought he could do better. One was nearby; the others would have required the family to move out of state. All paid somewhat less than he had previously earned.

While he says he's "not a bean counter," Mr. Joegriner now has mixed emotions about turning down the jobs. He estimates he has sent out about 3,000 copies of his résumé thus far. His severance package included the services of an outplacement firm, but he didn't find it helpful. "Unemployed people networking with other unemployed people has little value," he says.

After years of being a chief executive and hiring people, it's been a tough adjustment. Recently, he began shooting off his résumé for mid- and senior-level positions "just to try and land something." No replies.

Mr. Joegriner's mornings now start with a coffee run to the nearby 7-Eleven six days a week. While pouring his regular brew and a cup to take home to his wife, he calculates that by recycling the cups, he receives a 32-cent discount per $1.37 serving. That's a savings of $3.84 a week, he reckons -- even though this small "luxury" for the two of them still costs a total of about $655 a year.

Next, he typically spends a couple of hours doing home repairs. Since his layoff, he's installed a retaining wall, put under-cabinet lights in the kitchen and tiled a kitchen backsplash for a friend. "It's my Zen," he says. He's holding off outfitting a bathroom sink with a marble countertop.

By late morning, he launches into job-hunt mode. While trolling job web sites, Mr. Joegriner toggles to a multicolored, multitabulated Excel spreadsheet that calculates the household budget, as well as the "burn rate" through the family's dwindling savings.

Mr. Joegriner goes grocery shopping in the afternoon. Armed with coupons collected in a shoebox above the fridge, he strides down the aisles, striking out items from his wife's list with a black pen as he goes. His brow furrows reading the fine print on a cereal coupon his wife handed him. "It says $1.50 off cereal," he says. "But that's only if you buy three. So, really, it's only 50 cents off."

He pushes his grocery cart on a Friday afternoon through the full parking lot. "Sometimes I look at all this and think, 'Are we the only ones struggling?' You look around and see all these cars, it's like there's no recession."

Cutting expenses for their children, Ian and Skye, has been particularly tough, the couple says. Piano lessons are no more and birthday parties are small and held at home. Next year, private-school tuition, which costs $13,000 for the two children, will get the ax.

Mr. Joegriner doesn't use the word "unemployed" in front of his children, ages 9 and 6, preferring to say that he's a consultant and that income is patchy. Rough times have even moved him to contemplate seasonal employment this winter, "a stopgap job," while he continues his executive job search. "Maybe something at night stocking shelves," he says. "That way people wouldn't have to see me."

Mrs. Joegriner recently began looking for work as a paralegal. But finding an employer who can accommodate her schedule with the children, she says, has been difficult.

The Joegriner's four-bedroom residence is currently worth less than their $460,000 mortgage, but they're still making monthly payments of $2,400.

The couple is also saddled with two former residences -- which they once considered investment properties. While both are income-producing, low rents and declining real-estate values mean that they barely break even. At this point, any sale would likely result in a loss.

Originally committed to staying in the Washington, D.C., area, Mr. Joegriner expanded his search. In September, the family flew to tiny Gillette, Wyoming, where Mr. Joegriner was in the final interview stages for a CEO position at a credit union. The salary was $60,000 less than what he earned before, and uprooting his family from Maryland would be difficult. But they all seemed excited about a possible move.

A few days later, Mr. Joegriner received an offer and a contract. Despite the earlier enthusiasm, doubts began to surface. "What if we went all the way out there and they laid me off?" After fruitless negotiations, he turned down the job. The reason: The position didn't include a guarantee of severance pay. Says Mr. Joegriner: "I just couldn't take the risk."

No comments :

Post a Comment