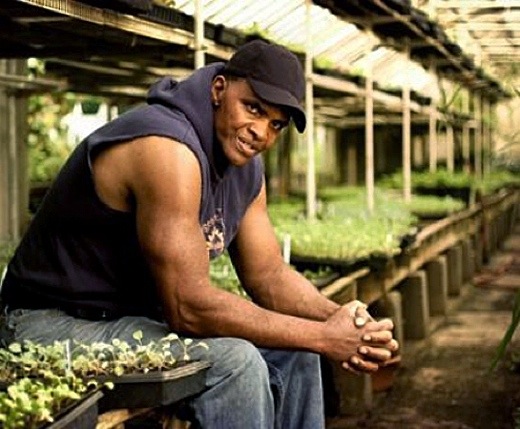

image above: Urban farmer Will Allen won a Genius Award from the McArthur Foundation

From http://solar1.org/2008/09/26/urban-farmer-wins-genius-award

By David Tracey on 17 August 2009 in The Tyee

http://thetyee.ca/News/2009/08/18/UrbanFarmingFuture

image above: Urban farmer Will Allen won a Genius Award from the McArthur Foundation

From http://solar1.org/2008/09/26/urban-farmer-wins-genius-award

By David Tracey on 17 August 2009 in The Tyee

http://thetyee.ca/News/2009/08/18/UrbanFarmingFuture

The first odd thing about Cam Macdonald's Mt. Pleasant lawn is that it isn't a lawn. It's a farm.

Standing out amid the typical suburban sea of grass patches are his potatoes, carrots, beats, peas, shallots, squash, parsnips and more -- enough to have given food to 70 people by the beginning of July.

The second odd thing is that it isn't even Cam's yard. It belongs to Heidi Gigler and Jug Sidhu, a non-gardening couple who heard about Cam's soul search for right livelihood last year and agreed to let him pursue it by turning their turf into food.

Does this small but significant act of land karma represent the beginning of a profound challenge to our very notions of private property and home ownership? Or is it just a simple way for a few more people to eat a little more food from where they live -- a driving force behind the soaring popularity of urban agriculture?

In any case, it's working. Cam is on his way to what could become a career, and the couple are thrilled with the look and taste of their front yard. "The problem," said Heidi, "is it's hard to keep up with the food."

They give some of the excess away to neighbours, including people they hardly knew before the creation of the front yard farm. "Now we're having constant conversations... It's really created a community."

Cam sees it as a first step. With his three partners, he hopes to hone his skills into a profitable business next year. Not bad for a guy who just got started in urban farming with little experience beyond "a year of reading a lot, talking to a lot of people who know what they're doing and just doing it."

It's only fair to mention that he did know a few things about indoor plants, having grown them during a self-apprenticeship in horticulture for which he now credits the Vancouver Police Department because it didn't arrest him. Of course growing food crops outdoors is different, but he swears it's not at all difficult. His advice: "Anyone can do it."

Many are, including some driven by a scary thought: we're running out of food.

Remember the global food crisis?

Until last fall when bankers took over the headlines, 2008 was known as "The Year of the Global Food Crisis."

Oddly, the crisis came at a time of world record grain harvests. Yet stockpiles went down and prices way up, to the breaking point.

Protesters marched in the streets of more than 20 countries. In the Philippines soldiers had to guard rice reserves. In Egypt the army was mobilized to bake bread.

Among the blamed was Big Ag, the corporations dominating industrial agriculture. Food giant Cargill saw its profits soar 86% during the worst of the crisis, while pesticide and seed seller Monsanto doubled its earnings, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Also pegged as part of the problem were commodity speculators, farmers planting bio-fuel rather than food crops, and swelling middle classes in China and India eating meat (animals need a lot of plants). Another probable cause was not always mentioned but may be the most ominous: peak oil.

Fossil fuels are used for the fertilizers and pesticides that power industrial agriculture. They're also burned to transport all those 2,400-mile salads. Our world food system was built on cheap oil, so if that era is about to end, it follows, so too is the way we eat, and live.

But hang on. It could get worse. And sooner than you think.

The mother of all monkey wrenches may be global climate change. Even in the near term, bigger storms and longer droughts will mean harder farming and fewer crops.

So with one crisis feeding another, which catastrophe will it be? Dwindling food stocks? Soaring energy costs? Global climate weirdness?

You could pick any one of them and worry yourself useless. Or you could do something about all three by growing a way out of the problem.

Can cities save agriculture?

It's called urban agriculture, and it's relatively new, at least on the scale now being tried. But it may be just what humanity needs if it's going to survive.

Too bold?

Let's break it down. Start with a simple question:

Can cities save agriculture?

Of course this would normally be asked the other way around. Rural farmers have fed urban residents since "agri" met "culture" 10,000 years ago.

It worked, and it didn't. Cities thrived, but not indefinitely. No society has ever been able to outlive its resources.

The limits, we realize now, as an urban species, with more than half our population in cities and a million more arriving every week, are planetary. Viewed through that lens, we can see a system being strained perhaps to the point of failure.

The worst effects are evident already in places like Botswana and Haiti. But not just there. In Canada more than 700,000 now visit food banks every month, including a rising number of families and those with jobs -- people confronting the new food realities for the first time.

If the old urban model based on exploiting surrounding resources won't work, the critical question of our time will be whether we can design livable cities without ruining the earth in the process. Or as educators in Queensland recently defined that clunky word "sustainability" for schoolchildren: we need to figure out how to provide "enough for everyone forever."

Ecology, energy, jobs, housing -- these and more will all figure in the ways we build a more sensible world, but the city of the future will largely be shaped by its food, something we're not used to considering in the big picture.

Food security, food systems, food sovereignty, food policy. If these terms aren't familiar yet, they may well be soon. Others will emerge as the movement grows. The model city of the 21st century may turn out to be a living, green, healthy place in harmony with its own "foodshed," unless that sounds too much like a pantry in the back yard.

BC could be a leading example

We know a population of billions will still need large rural farms. And we hope we can always share the benefits of fair trading on a small planet, because no amount of eco-guilt will ever convince some (me) that drinking tea in Canada is a terrible thing.

But we are heading into an era where many more people will have to reconnect significantly with their food in all its stages: growing, distributing, preparing, eating, recycling. Starting with growing.

Urban agriculture is spreading in B.C. and around the world. Rarely mentioned a generation ago, it's the buzz term of our day.

It already offers an estimated 800 million farmers a chance to shape their own urban environment, cut grocery budgets, eat fresh produce, reduce carbon emissions, beautify developed areas, re-engage with rural growers and, fingers crossed, maybe even save the planet.

Modern urban agriculture is still in the experimental stages. In some places it's hip, in others a way to survive. Just how it turns out, and what the term means 25 years from now, is still to be determined, perhaps with our help.

British Columbians can lead the world in offering an enlightened model of city living centred on healthy food for all.

Why us?

Our cities are still new, on the historical scale, so we're not bound by medieval property lines or centuries-old thinking.

We like to think of ourselves as innovative in urban design, and willing to try new ideas if they'll lead to a healthier environment.

We have good growing conditions: rich soil, clean water and weather mild enough, near the coast anyway, to support year-round harvests of fresh greens.

We've escaped the worst of the urban sprawl riddling other regions in North America, thanks to the farmland protection act known as the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR).

We'll back our growers where it counts, at the cash register, according to an Ipsos Reid poll that found eight out of 10 people willing to pay a premium for food that's fresh, local and grown with fewer chemicals and pesticides.

Finally, we're mad to grow it ourselves, to judge by the booming sales of vegetable seeds and long waiting lists for community garden plots.

Get dirty

Explanations for why so many more people are eager to grow their own food vary, but at least some of the interest stems from the urban angst brought on by all the predictions of a bleak environmental future.

So to put the answer to our simple question in simple terms: cities must save agriculture because nothing else can, and vice versa.

The appeal of doing something, with your hands in the soil, offers anyone a chance to be in on the solution. You could wallow in the end of the world as we know it, or you could take an active role as an engaged citizen while you bite into a sun-warmed tomato fresh off the vine. Which side are you on?

This series explores the boom in urban agriculture in British Columbia by looking at how we got here, how we rate comparatively and, most importantly, what we should be doing now to create a better food future.

No comments :

Post a Comment