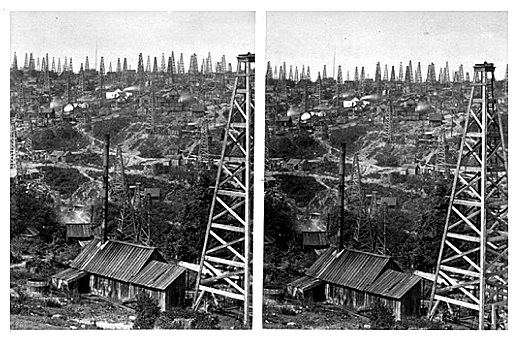

image above: Stereopticon photos of oil field in Pennsylvania with shooting well produced with eighty quarts of nitro glycerine.

Created by Keystone View Company and reproduced in Wired article.

image above: Stereopticon photos of oil field in Pennsylvania with shooting well produced with eighty quarts of nitro glycerine.

Created by Keystone View Company and reproduced in Wired article.

One hundred and fifty years ago on Aug. 27, Colonel Edwin L. Drake sunk the very first commercial well that produced flowing petroleum.

The discovery that large amounts of oil could be found underground marked the beginning of a time during which this convenient fossil fuel became America’s dominant energy source.

But what began 150 years ago won’t last another 150 years — or even another 50. The era of cheap oil is ending, and with another energy transition upon us, we’ve got to scavenge all the lessons we can from its remarkable history.

“I would see this as less of an anniversary to note for celebration and more of an anniversary to note how far we’ve come and the serious moment that we’re at right now,” said Brian Black, an energy historian at Pennsylvania State University and and author of the book Petrolia. “Energy transitions happen and I argue that we’re in one right now and that we need to aggressively look to the future to what’s going to happen after petroleum.”

When Drake and others sunk their wells, there were no cars, no plastics, no chemical industry. Water power was the dominant industrial energy source. Steam engines burning coal were on the rise, but the nation’s energy system — unlike Great Britain’s — still used fossil fuels sparingly. The original role for oil was as an illuminant, not a motor fuel, which would come decades later.

Before the 1860s, petroleum was a well-known curiosity. People collected it with blankets or skimmed it off naturally occurring oil seeps. Occasionally they drank some of it as a medicine or rubbed it on aching joints.

Some people had the bright idea of distilling it to make fuel for lamps, but it was easier to get lamp fuel from pig fat or whale oil or converted coal. Without a steady supply, there was no point in developing a whole system and infrastructure dedicated to petroleum.

Nonetheless, some Yankee capitalists from Connecticut were convinced that oil could be found in the ground and exploited. They recruited “Colonel” Edwin Drake, who was not a Colonel at all, mostly because he was charming and unemployed. He, in turn, found someone skilled in the art of drilling, or what passed for it in those days.

Drake and his sidekick “Uncle Billy” Smith started looking underground for oil in the spring of ‘59. They used a heavy metal tip attached to a rope, sending it plummeting down the borehole like a ram to break up the rock. It was slow going.

On Aug. 27, 1859, at 69 feet of depth, Drake and Smith hit oil. It was a big deal, but the Civil War stalled the immediate development of the rock oil industry.

“When the discovery happened, the few people who were there and not involved in the war, went around and bought all the property they could and had outside investors come in,” Black said. “But the real heyday of the development happened from 1864-1870. It’s that 11-year period when the little river valley was the world’s leading supplier of oil.”

image above: Stereopticon photos of a forest of derricks in 19th century central Pennsylvania

image above: Stereopticon photos of a forest of derricks in 19th century central Pennsylvania

The “little river valley” in western Pennsylvania earned the nickname Petrolia. Centered in the Oil Creek valley about one hundred miles north of Pittsburgh, the wells of Pithole, Titusville and Oil City pumped 56 million barrels of oil out of the ground from 1859 to 1873.

Suddenly, rock oil was everywhere. And cheap. Whale oil had always been a bit precious. A three to five year voyage would only yield a few thousand gallons of the stuff. In 1866, after the end of the Civil War, 3.6 million barrels poured out of the region. Daniel Yergin notes in his history of oil, The Prize, that as more people poured into the oil regions “supply outran demand” and soon the whiskey barrels that held the oil “cost almost twice as much as the oil inside them.”

Still, fortunes were being made and lost. Not just money, but energy, was flowing from underground. Some have estimated that for every unit of energy you invested sinking a well, you got back “more than 100 times as much usable energy.

Oil, people soon found, was uniquely convenient. To equal get the amount of energy in a tank of gasoline, you need 200 pounds of wood. Pair that energy density with stability under most conditions (meaning it didn’t randomly explode), and that, as a liquid, it was easy to transport, and you have the killer app for the infrastructure age.

In a world that only had a tiny fraction of the amount of heat, light, and power available that we do now, people came up with all kinds of ideas for what to do with oil’s energy: cars, tractors, airplanes, chemicals, fertilizer, and plastic.

Perhaps it’s not a surprising consequence of this innovation that at current consumption levels, Americans would blow through all the oil ever produced in Petrolia in less than three days.

The scale of the oil industry is astounding, but it’s becoming clear the world’s oil supply will peak soon, or perhaps has peaked already. People quibble about the details, but no one argues that oil will play a much different role in our energy system in 50 years than it did in 1959.

The search for alternatives is on. If that search goes poorly — as some Peak Oil analysts predict — human civilization will fall off an energy cliff. The amount of energy we get back from drilling oil wells in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico continues to drop, and alternative sources don’t provide usable energy for humans on the generous terms that oil long has.

But humans with an economic incentive to be optimistic become optimists, and the harder we look, the more possible alternatives we find. The big question now is whether the cure for our oil addiction will come with a heavy carbon side effect.

“Peak oil and peak gas and coal could really go either way for the climate,” Pushker Kharecha, a scientist with NASA’s Global Institute for Space Studies, said at least year’s American Geophysical Union meeting. “It all depends on choices for subsequent energy sources.”

Over the next 20 years, synthetic fuels made from coal or shale oil could conceivably become the fuels of the future. On the other hand, so could advanced biofuels from cellulosic ethanol or algae. Or the era of fuel could end and electric vehicles could be deployed in mass, at least in rich countries.

With the massive injection of stimulus and venture capital money into alternative energy that’s occurred over the past few years, the solutions for replacing oil could already be circulating among the labs and office parks of the country. To paraphrase technology pundit Clay Shirky talking about the media, nothing will work to replace oil, but everything might.

If history tells us anything, it’s that energy sources can change, never tomorrow, but always some day.

“What is required is to operate without fear and to take energy transitions on as a developmental opportunity,” Black said.

No comments :

Post a Comment