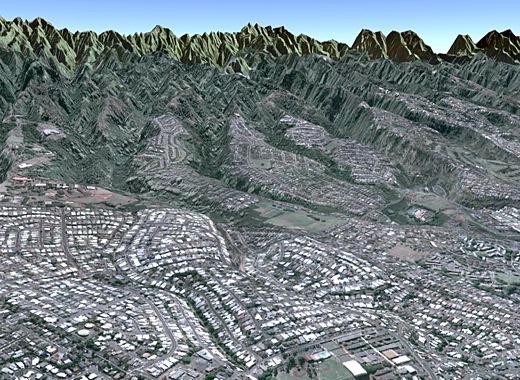

Image above: Suburban development near Pearl City on what was once field and forest. GoogleEarth image by Juan Wilson.

Image above: Suburban development near Pearl City on what was once field and forest. GoogleEarth image by Juan Wilson.

The 1978 Constitutional Convention was the most significant moment in Hawaii politics since statehood. Among other sweeping reforms–the creation of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the balanced-budget requirement, the establishment of term limits and the adoption of ‘Olelo Hawaii as one of two official state languages–delegates proposed an amendment designed to protect agriculture in perpetuity.

A generation ago, sugar was everywhere in the Islands, but the industry was well into its decline. Con-Con delegates, led by young Kauai biology professor–and future Honolulu mayor–Jeremy Harris, worried along with the rest of the Islands that out-of-control housing development would overwhelm Hawaii agriculture.

The result of the convention’s discussions was this passage:

“The State shall conserve and protect agricultural lands, promote diversified agriculture, increase agricultural self-sufficiency and assure the availability of agriculturally suitable lands…Lands identified by the State as important agricultural lands needed to fulfill the purposes above shall not be reclassified by the State or rezoned by its political subdivisions without meeting the standards and criteria established by the legislature and approved by a two-thirds vote of the body responsible for the reclassification or rezoning action.”

Sustainability, it turns out, was on the agenda in 1978–and not only on the minds of idealistic young convention delegates. The Important Agricultural Lands amendment went onto the ballot that fall, where it was approved by voters as Article XI ,Section 3.

Had the state government acted then–that is, had it fulfilled a constitutionally mandated duty to keep agricultural land in the hands of farmers–Hawaii would almost certainly be a very different place in 2010. In the years following the Con-Con, the collapse of Hawaii’s sugar and pineapple industries left thousands of acres of prime farmland open to new uses, and developers were ready to satisfy skyrocketing demand for housing. The housing industry thrived, the farming industry–from monoculture to family farms–nose-dived, and Hawaii woke from three decades of breathless growth–dreamy or nightmarish, depending on where you stand–into a strange new century of tourism and, well, nothing else. In the face of these forces, the state did nothing on Important Agricultural Lands for almost 30 years.

Clift Tsuji was elected to the State House of Representatives from the Hilo area in 2004. He now chairs the Agriculture Committee. “Immediately,” he said last week, “I was given the historic background of all of this, and a number of lawmakers said, ‘We’ve been trying to do this for 30 years, and nothing has happened and it just goes on and on.’” Tsuji said the issue immediately became a priority. “Hawaii was built on ag. The economic demise of agriculture is well known. If we have any thoughts of trying to put ag in the forefront, we better get off our bottoms and start doing something.”

But do what? Voters had approved the constitutional amendment in broad form, but over the decades of inaction, no one had been able to agree on what constituted important ag land, how it would be mapped and inventoried, or what kinds of incentives and compensation would be offered to landowners whose property was deemed too agriculturally important to ever be rezoned.

In 2005, the Legislature passed Act 183, which established–finally–the standards and criteria for the determination of what farmlands should be protected in perpetuity. Among the most important criteria:

• Capable of producing sustained high agricultural yields when treated and managed according to accepted farming methods and technology. • Economic value, whether for export or consumption. • Viability for future use, even among lands not currently in production. • High soil quality. • Value for traditional Hawaiian agricultural uses, such as taro cultivation. • Viability for coffee, vineyards, aquaculture. • Potential for biofuels. • Access to water. • Access to infrastructure needed to make agriculture viable, particularly roads.

Left unanswered in 2005, however, were the twin questions of how to compensate landowners for taking their lands out of possible rezoning and redevelopment essentially forever, and how to ensure that the state actually accomplished the purpose of the IAL amendment, which was not about zoning, after all, but about ensuring a viable agricultural future for Hawaii.

Three years later, in 2008, Act 233 finally brought IAL into a kind of reality by responding to these questions. The law set up a detailed process of compensation for landowners and established a timeline for landowners to voluntarily designate 85 percent of their holdings as IAL, in exchange for what amounts to a fast-tracked development process on the remaining 15 percent. In short, this means that a landholder could agree to set aside 8,500 acres from residential development permanently, with the assurance that the remaining 1,500 would receive an expedited–though not guaranteed–permitting and rezoning process.

For farmers themselves, Act 233 promised substantial tax credits and other subsidies designed to make farming more viable in the Islands. These include loan guarantees, lending at below-market rates and a range of tax-credits for investment in agricultural infrastructure.

That was critical, says David Arakawa, director of the Land Use Research Foundation of Hawaii, because it clarified that Important Agricultural Lands law is in fact not primarily about land, but about farming.

“The IAL process has taken a long time, but more important than a sense of urgency is the understanding, which is emerging, that this is a new paradigm for Hawaii. IAL is first and foremost about supporting farmers. It’s not about how much land you take. You can have all the land in the world. If you don’t have water, and you don’t have labor, and you don’t have incentives, you can designate all the land you want, and you’re only going to have soil and stone.”

The law also established a window–set to close on July 1, 2011–for landowners to voluntarily designate land as IAL. After that point, it will be left to the counties to prepare their own IAL maps, and for the state Land Use Commission to unilaterally designate lands. All of the incentives–including the 85/15 rule–will still apply.

Alexander & Baldwin has been the first major landowner to step into the IAL process, having designated more than 27,000 acres on Maui and 3,700 on Kauai since 2009. According to a Honolulu city official who asked not to be identified, both Kamehameha Schools and Castle & Cooke are in the process of preparing designations.

With the voluntary deadline just a year away, only Kauai County has so far begun the process of preparing its IAL maps–because only Kauai had state funding with which to do it.

On Oahu, City Councilman Donovan Dela Cruz put money into the budget for the project this summer. “The state didn’t give the counties the funding. Most time there’s an unfunded mandate, the countries won’t do it, and that’s what happened with IAL. I put half a million into the budget this year so we can do this.”

Earlier this month, Arakawa, who is part of the city’s Agricultural Development Task Force, called for the city to begin work on mapping the IAL in anticipation of next summer’s deadline on voluntary designation.

Bill Brennan, spokesman for Mayor Mufi Hannemann, could not immediately say where the city was on the release of the funding, but one official, who asked not to be named, said the city’s planning department was simply waiting for the funds to become available.

Going forward, Arakawa and Nalo Farms owner Dean Okimoto both say that IAL is long overdue, but caution that the designation of land will not in itself revitalize farming in Hawaii.

Arakawa actually points to Okimoto, who is on leave as head of the Hawaii Farm Bureau, as an example of how strapped farmers truly are. “Who’s the most famous farmer in Hawaii? Maybe Richard Ha on the Big Island, maybe the folks at MAO Organic Farm, but probably Dean Okimoto. Guess how many acres this guy, this giant of farming has in production? Five. Five acres. If that doesn’t tell you what’s going on, nothing will.”

“There are some good incentives in place but if we could get everything that was necessary, it would make more of a difference,” says Okimoto. He says red-tape at the county level is a significant hindrance to many farmers looking to expand.

“Look at me–it took me almost two years to go through the permitting process for a new processing facility. That raised our costs from $500,000 to $1.8 million, just because it took so long. It’s put me in jeopardy basically. We definitely need an expedited process, and more incentives for farmers to invest in the future.”

See also: County of Kauai Important Agricultural Lands Study (http://sites.google.com/site/kauaiial/home/legislation)

.

No comments :

Post a Comment