By Jay Griffiths on 24 June 2009 in Orion Magazine -

(http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/4792)

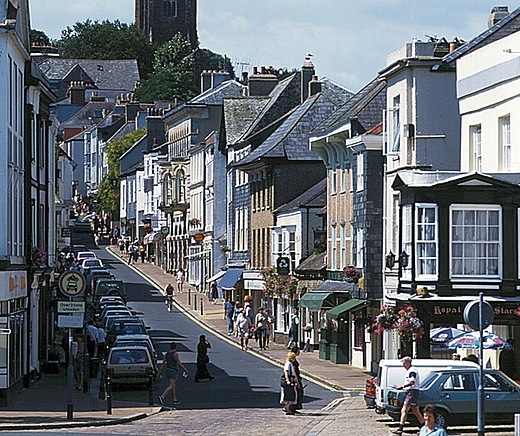

Image above: Totnes, the first Transition Town in Devon, England. From http://www.devonbuildingcontrol.gov.uk/html/totnes.html

A while ago, I heard an American scientist address an audience in Oxford, England, about his work on the climate crisis. He was precise, unemotional, rigorous, and impersonal: all strengths of a scientist.

The next day, talking informally to a small group, he pulled out of his wallet a much-loved photo of his thirteen-year-old son. He spoke as carefully as he had before, but this time his voice was sad, worried, and fatherly. His son, he said, had become so frightened about climate change that he was debilitated, depressed, and disturbed. Some might have suggested therapy, Prozac, or baseball for the child. But in this group one voice said gently, “What about the Transition Initiative?”

If the Transition Initiative were a person, you’d say he or she was charismatic, wise, practical, positive, resourceful, and very, very popular. Starting with the town of Totnes in Devon, England, in September 2006, the movement has spread like wildfire across the U.K. (delightfully wriggling its way into The Archers, Britain’s longest-running and most popular radio soap opera), and on to the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. The core purpose of the Transition Initiative is to address, at the community level, the twin issues of climate change and peak oil—the declining availability of “ancient sunlight,” as fossil fuels have been called. The initiative is set up to enable towns or neighborhoods to plan for, and move toward, a post-oil and low-carbon future: what Rob Hopkins, founder of the Transition Initiative, has termed “the great transition of our time, away from fossil fuels.”

Part of the genius of the movement rests in its acute and kind psychology. It acknowledges the emotional effect of these issues, from that thirteen-year-old’s sense of fear and despair, to common feelings of anger, impotence, and denial, and it uses insights from the psychology of addiction to address some reasons why it is hard for people to detoxify themselves from an addiction to (or dependence on) oil. It acknowledges that healthy psychological functioning depends on a belief that one’s needs will be met in the future; for an entire generation, that belief is now corroded by anxiety over climate change.

Many people feel that individual action on climate change is too trivial to be effective but that they are unable to influence anything at a national, governmental level. They find themselves paralyzed between the apparent futility of the small-scale and impotence in the large-scale. The Transition Initiative works right in the middle, at the scale of the community, where actions are significant, visible, and effective. “What it takes is a scale at which one can feel a degree of control over the processes of life, at which individuals become neighbors and lovers instead of just acquaintances and ciphers. . . participants and protagonists instead of just voters and taxpayers. That scale is the human scale,” wrote author and secessionist Kirkpatrick Sale in his 1980 book, Human Scale.

How big am I? As an individual, five foot two and whistling. At a government level, I find I’ve shrunk, smaller than the X on my ballot paper. But at a community level, I can breathe in five river-sources and breathe out three miles of green valleys.

Scale matters.

We speak of economies of scale, and I would suggest that there are also moralities of scale. At the individual scale, morality is capricious: people can be heroes or mass murderers, but the individual is usually constrained by inner conscience and always constrained by size. While a nation-state can at best offer a meager welfare system, at worst—as the history of nations in the twentieth century showed so brutally—morality need not be constrained by any conscience, and through its enormity a state can engineer a genocide. At the community level, though, morality is complex: certainly communities can be jealous and spiteful and less given to heroism than an individual, yet a community’s power to harm is far less than that of a state, simply because of its size. Further, because there are more niche reasons for people to identify with their community, and simply because there is a greater per-capita responsibility, a community is more susceptible to a sense of shame. Community morality involves a sense of fellow-feeling, is attuned to the common good, far steadier than individual morality, far kinder than the State: its moral range reaches neither heaven nor hell but is grounded, well-rooted in the level of Earth.

STARTING WITH a steering group of just a handful of people in one locality, the motivation to become a Transition community spreads, often through many months of preparation, information-giving, and awareness-raising of the issues of climate change and peak oil. In those months, there are talks and film screenings, and a deliberate attempt to encourage a sense of a community’s resilience in the face of stresses. When members of the steering group judge that there is enough support and momentum for the project, it is launched, or “unleashed.”

Keeping an eye on the prize (reducing carbon emissions and oil dependence), Transition communities have then looked at their own situation in various practical frames—for example, food production, energy use, building, waste, and transport—seeking to move toward a situation where a community could be self-reliant. At this stage, the steering group steps back, and various subgroups can form around specific aspects of transitioning. Strategies have included the promotion of local food production, planting fruit trees in public spaces, community gardening, and community composting. In terms of energy use, some communities have begun “oil vulnerability auditing” for local businesses, and some have sought to re-plan local transport for “life beyond the car.” In one Transition Town there are plans to make local, renewable energy a resource owned by the community, in another there are plans to bulk-buy solar panels as a cooperative and sell them locally without profit. There are projects of seed saving, seed swapping, and creating allotments—small parcels of land on which individuals can grow fruit and vegetables.

“The people who see the value of changing the system are ordinary people, doing it for their children,” says Naresh Giangrande, who was involved in setting up the first Transition Town. “The political process is corrupted by money, power, and vested interests. I’m not writing off large corporations and government, but because they have such an investment in this system, they haven’t got an incentive to change. I can only see us getting sustainable societies from the grassroots, bottom-up, and only that way can we get governments to change.” In the States, the “350” project (the international effort to underscore the need to decrease atmospheric carbon dioxide to 350 parts per million) is similarly asking ordinary people to signal to those in power. If change doesn’t come from above, it must come from below, and politicians would be unwise to ignore the concern about peak oil and climate change coming from the grassroots.

The grassroots. Both metaphorically and literally. Transition Initiative founder Rob Hopkins used to be a permaculture teacher, and permaculture’s influence is wide and deep. As permaculture works with, rather than against, nature, so the Transition Initiative works with, rather than against, human nature; it is as collaborative and cooperative in social tone as permaculture is in its attitude toward plants and, like permaculture, is prepared to observe and think, slowly.

One of the subgroups that Transition communities typically use is called “Heart and Soul,” which focuses on the psychological and emotional aspects of climate crisis, of change, of community. Importantly, people are encouraged to be participants in the conversation, not just passive spectators: it is a nurturant process, involving anyone who wants to be a part. Good conversation involves quality listening, for an open-minded, attentive listener can elicit the best thoughts of a speaker. Giangrande says that the Transition Initiative—which has used keynote speakers—is also exploring the idea of keynote listeners as “a collaborative way of learning how to use knowledge.” When I asked exactly what that would involve, he couldn’t be specific, because it was still only an idea, which is revealing of the Transition process, very much a work-in-progress. The fact that they were trying out an idea without being able to predict the results has a vitality to it, an intellectually energetic quality, a profound liveliness.

The Transition Initiative describes itself as a catalyst, with no fixed answers, unlike traditional environmentalism, which is more prescriptive, advocating certain responses. Again unlike conventional environmentalism, it emphasizes the role of hope and proactiveness, rather than guilt and fear as motivators. Whether intentionally or not, environmentalism can seem exclusive, and the Transition Initiative is whole-heartedly inclusive.

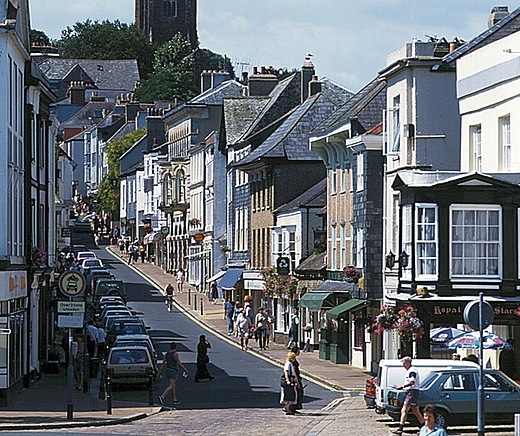

Image above: Totnes, the first Transition Town in Devon, England. From http://www.devonbuildingcontrol.gov.uk/html/totnes.html

A while ago, I heard an American scientist address an audience in Oxford, England, about his work on the climate crisis. He was precise, unemotional, rigorous, and impersonal: all strengths of a scientist.

The next day, talking informally to a small group, he pulled out of his wallet a much-loved photo of his thirteen-year-old son. He spoke as carefully as he had before, but this time his voice was sad, worried, and fatherly. His son, he said, had become so frightened about climate change that he was debilitated, depressed, and disturbed. Some might have suggested therapy, Prozac, or baseball for the child. But in this group one voice said gently, “What about the Transition Initiative?”

If the Transition Initiative were a person, you’d say he or she was charismatic, wise, practical, positive, resourceful, and very, very popular. Starting with the town of Totnes in Devon, England, in September 2006, the movement has spread like wildfire across the U.K. (delightfully wriggling its way into The Archers, Britain’s longest-running and most popular radio soap opera), and on to the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. The core purpose of the Transition Initiative is to address, at the community level, the twin issues of climate change and peak oil—the declining availability of “ancient sunlight,” as fossil fuels have been called. The initiative is set up to enable towns or neighborhoods to plan for, and move toward, a post-oil and low-carbon future: what Rob Hopkins, founder of the Transition Initiative, has termed “the great transition of our time, away from fossil fuels.”

Part of the genius of the movement rests in its acute and kind psychology. It acknowledges the emotional effect of these issues, from that thirteen-year-old’s sense of fear and despair, to common feelings of anger, impotence, and denial, and it uses insights from the psychology of addiction to address some reasons why it is hard for people to detoxify themselves from an addiction to (or dependence on) oil. It acknowledges that healthy psychological functioning depends on a belief that one’s needs will be met in the future; for an entire generation, that belief is now corroded by anxiety over climate change.

Many people feel that individual action on climate change is too trivial to be effective but that they are unable to influence anything at a national, governmental level. They find themselves paralyzed between the apparent futility of the small-scale and impotence in the large-scale. The Transition Initiative works right in the middle, at the scale of the community, where actions are significant, visible, and effective. “What it takes is a scale at which one can feel a degree of control over the processes of life, at which individuals become neighbors and lovers instead of just acquaintances and ciphers. . . participants and protagonists instead of just voters and taxpayers. That scale is the human scale,” wrote author and secessionist Kirkpatrick Sale in his 1980 book, Human Scale.

How big am I? As an individual, five foot two and whistling. At a government level, I find I’ve shrunk, smaller than the X on my ballot paper. But at a community level, I can breathe in five river-sources and breathe out three miles of green valleys.

Scale matters.

We speak of economies of scale, and I would suggest that there are also moralities of scale. At the individual scale, morality is capricious: people can be heroes or mass murderers, but the individual is usually constrained by inner conscience and always constrained by size. While a nation-state can at best offer a meager welfare system, at worst—as the history of nations in the twentieth century showed so brutally—morality need not be constrained by any conscience, and through its enormity a state can engineer a genocide. At the community level, though, morality is complex: certainly communities can be jealous and spiteful and less given to heroism than an individual, yet a community’s power to harm is far less than that of a state, simply because of its size. Further, because there are more niche reasons for people to identify with their community, and simply because there is a greater per-capita responsibility, a community is more susceptible to a sense of shame. Community morality involves a sense of fellow-feeling, is attuned to the common good, far steadier than individual morality, far kinder than the State: its moral range reaches neither heaven nor hell but is grounded, well-rooted in the level of Earth.

STARTING WITH a steering group of just a handful of people in one locality, the motivation to become a Transition community spreads, often through many months of preparation, information-giving, and awareness-raising of the issues of climate change and peak oil. In those months, there are talks and film screenings, and a deliberate attempt to encourage a sense of a community’s resilience in the face of stresses. When members of the steering group judge that there is enough support and momentum for the project, it is launched, or “unleashed.”

Keeping an eye on the prize (reducing carbon emissions and oil dependence), Transition communities have then looked at their own situation in various practical frames—for example, food production, energy use, building, waste, and transport—seeking to move toward a situation where a community could be self-reliant. At this stage, the steering group steps back, and various subgroups can form around specific aspects of transitioning. Strategies have included the promotion of local food production, planting fruit trees in public spaces, community gardening, and community composting. In terms of energy use, some communities have begun “oil vulnerability auditing” for local businesses, and some have sought to re-plan local transport for “life beyond the car.” In one Transition Town there are plans to make local, renewable energy a resource owned by the community, in another there are plans to bulk-buy solar panels as a cooperative and sell them locally without profit. There are projects of seed saving, seed swapping, and creating allotments—small parcels of land on which individuals can grow fruit and vegetables.

“The people who see the value of changing the system are ordinary people, doing it for their children,” says Naresh Giangrande, who was involved in setting up the first Transition Town. “The political process is corrupted by money, power, and vested interests. I’m not writing off large corporations and government, but because they have such an investment in this system, they haven’t got an incentive to change. I can only see us getting sustainable societies from the grassroots, bottom-up, and only that way can we get governments to change.” In the States, the “350” project (the international effort to underscore the need to decrease atmospheric carbon dioxide to 350 parts per million) is similarly asking ordinary people to signal to those in power. If change doesn’t come from above, it must come from below, and politicians would be unwise to ignore the concern about peak oil and climate change coming from the grassroots.

The grassroots. Both metaphorically and literally. Transition Initiative founder Rob Hopkins used to be a permaculture teacher, and permaculture’s influence is wide and deep. As permaculture works with, rather than against, nature, so the Transition Initiative works with, rather than against, human nature; it is as collaborative and cooperative in social tone as permaculture is in its attitude toward plants and, like permaculture, is prepared to observe and think, slowly.

One of the subgroups that Transition communities typically use is called “Heart and Soul,” which focuses on the psychological and emotional aspects of climate crisis, of change, of community. Importantly, people are encouraged to be participants in the conversation, not just passive spectators: it is a nurturant process, involving anyone who wants to be a part. Good conversation involves quality listening, for an open-minded, attentive listener can elicit the best thoughts of a speaker. Giangrande says that the Transition Initiative—which has used keynote speakers—is also exploring the idea of keynote listeners as “a collaborative way of learning how to use knowledge.” When I asked exactly what that would involve, he couldn’t be specific, because it was still only an idea, which is revealing of the Transition process, very much a work-in-progress. The fact that they were trying out an idea without being able to predict the results has a vitality to it, an intellectually energetic quality, a profound liveliness.

The Transition Initiative describes itself as a catalyst, with no fixed answers, unlike traditional environmentalism, which is more prescriptive, advocating certain responses. Again unlike conventional environmentalism, it emphasizes the role of hope and proactiveness, rather than guilt and fear as motivators. Whether intentionally or not, environmentalism can seem exclusive, and the Transition Initiative is whole-heartedly inclusive.

Image above: Totnes, the first Transition Town in Devon, England. From http://www.devonbuildingcontrol.gov.uk/html/totnes.html

A while ago, I heard an American scientist address an audience in Oxford, England, about his work on the climate crisis. He was precise, unemotional, rigorous, and impersonal: all strengths of a scientist.

The next day, talking informally to a small group, he pulled out of his wallet a much-loved photo of his thirteen-year-old son. He spoke as carefully as he had before, but this time his voice was sad, worried, and fatherly. His son, he said, had become so frightened about climate change that he was debilitated, depressed, and disturbed. Some might have suggested therapy, Prozac, or baseball for the child. But in this group one voice said gently, “What about the Transition Initiative?”

If the Transition Initiative were a person, you’d say he or she was charismatic, wise, practical, positive, resourceful, and very, very popular. Starting with the town of Totnes in Devon, England, in September 2006, the movement has spread like wildfire across the U.K. (delightfully wriggling its way into The Archers, Britain’s longest-running and most popular radio soap opera), and on to the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. The core purpose of the Transition Initiative is to address, at the community level, the twin issues of climate change and peak oil—the declining availability of “ancient sunlight,” as fossil fuels have been called. The initiative is set up to enable towns or neighborhoods to plan for, and move toward, a post-oil and low-carbon future: what Rob Hopkins, founder of the Transition Initiative, has termed “the great transition of our time, away from fossil fuels.”

Part of the genius of the movement rests in its acute and kind psychology. It acknowledges the emotional effect of these issues, from that thirteen-year-old’s sense of fear and despair, to common feelings of anger, impotence, and denial, and it uses insights from the psychology of addiction to address some reasons why it is hard for people to detoxify themselves from an addiction to (or dependence on) oil. It acknowledges that healthy psychological functioning depends on a belief that one’s needs will be met in the future; for an entire generation, that belief is now corroded by anxiety over climate change.

Many people feel that individual action on climate change is too trivial to be effective but that they are unable to influence anything at a national, governmental level. They find themselves paralyzed between the apparent futility of the small-scale and impotence in the large-scale. The Transition Initiative works right in the middle, at the scale of the community, where actions are significant, visible, and effective. “What it takes is a scale at which one can feel a degree of control over the processes of life, at which individuals become neighbors and lovers instead of just acquaintances and ciphers. . . participants and protagonists instead of just voters and taxpayers. That scale is the human scale,” wrote author and secessionist Kirkpatrick Sale in his 1980 book, Human Scale.

How big am I? As an individual, five foot two and whistling. At a government level, I find I’ve shrunk, smaller than the X on my ballot paper. But at a community level, I can breathe in five river-sources and breathe out three miles of green valleys.

Scale matters.

We speak of economies of scale, and I would suggest that there are also moralities of scale. At the individual scale, morality is capricious: people can be heroes or mass murderers, but the individual is usually constrained by inner conscience and always constrained by size. While a nation-state can at best offer a meager welfare system, at worst—as the history of nations in the twentieth century showed so brutally—morality need not be constrained by any conscience, and through its enormity a state can engineer a genocide. At the community level, though, morality is complex: certainly communities can be jealous and spiteful and less given to heroism than an individual, yet a community’s power to harm is far less than that of a state, simply because of its size. Further, because there are more niche reasons for people to identify with their community, and simply because there is a greater per-capita responsibility, a community is more susceptible to a sense of shame. Community morality involves a sense of fellow-feeling, is attuned to the common good, far steadier than individual morality, far kinder than the State: its moral range reaches neither heaven nor hell but is grounded, well-rooted in the level of Earth.

STARTING WITH a steering group of just a handful of people in one locality, the motivation to become a Transition community spreads, often through many months of preparation, information-giving, and awareness-raising of the issues of climate change and peak oil. In those months, there are talks and film screenings, and a deliberate attempt to encourage a sense of a community’s resilience in the face of stresses. When members of the steering group judge that there is enough support and momentum for the project, it is launched, or “unleashed.”

Keeping an eye on the prize (reducing carbon emissions and oil dependence), Transition communities have then looked at their own situation in various practical frames—for example, food production, energy use, building, waste, and transport—seeking to move toward a situation where a community could be self-reliant. At this stage, the steering group steps back, and various subgroups can form around specific aspects of transitioning. Strategies have included the promotion of local food production, planting fruit trees in public spaces, community gardening, and community composting. In terms of energy use, some communities have begun “oil vulnerability auditing” for local businesses, and some have sought to re-plan local transport for “life beyond the car.” In one Transition Town there are plans to make local, renewable energy a resource owned by the community, in another there are plans to bulk-buy solar panels as a cooperative and sell them locally without profit. There are projects of seed saving, seed swapping, and creating allotments—small parcels of land on which individuals can grow fruit and vegetables.

“The people who see the value of changing the system are ordinary people, doing it for their children,” says Naresh Giangrande, who was involved in setting up the first Transition Town. “The political process is corrupted by money, power, and vested interests. I’m not writing off large corporations and government, but because they have such an investment in this system, they haven’t got an incentive to change. I can only see us getting sustainable societies from the grassroots, bottom-up, and only that way can we get governments to change.” In the States, the “350” project (the international effort to underscore the need to decrease atmospheric carbon dioxide to 350 parts per million) is similarly asking ordinary people to signal to those in power. If change doesn’t come from above, it must come from below, and politicians would be unwise to ignore the concern about peak oil and climate change coming from the grassroots.

The grassroots. Both metaphorically and literally. Transition Initiative founder Rob Hopkins used to be a permaculture teacher, and permaculture’s influence is wide and deep. As permaculture works with, rather than against, nature, so the Transition Initiative works with, rather than against, human nature; it is as collaborative and cooperative in social tone as permaculture is in its attitude toward plants and, like permaculture, is prepared to observe and think, slowly.

One of the subgroups that Transition communities typically use is called “Heart and Soul,” which focuses on the psychological and emotional aspects of climate crisis, of change, of community. Importantly, people are encouraged to be participants in the conversation, not just passive spectators: it is a nurturant process, involving anyone who wants to be a part. Good conversation involves quality listening, for an open-minded, attentive listener can elicit the best thoughts of a speaker. Giangrande says that the Transition Initiative—which has used keynote speakers—is also exploring the idea of keynote listeners as “a collaborative way of learning how to use knowledge.” When I asked exactly what that would involve, he couldn’t be specific, because it was still only an idea, which is revealing of the Transition process, very much a work-in-progress. The fact that they were trying out an idea without being able to predict the results has a vitality to it, an intellectually energetic quality, a profound liveliness.

The Transition Initiative describes itself as a catalyst, with no fixed answers, unlike traditional environmentalism, which is more prescriptive, advocating certain responses. Again unlike conventional environmentalism, it emphasizes the role of hope and proactiveness, rather than guilt and fear as motivators. Whether intentionally or not, environmentalism can seem exclusive, and the Transition Initiative is whole-heartedly inclusive.

Image above: Totnes, the first Transition Town in Devon, England. From http://www.devonbuildingcontrol.gov.uk/html/totnes.html

A while ago, I heard an American scientist address an audience in Oxford, England, about his work on the climate crisis. He was precise, unemotional, rigorous, and impersonal: all strengths of a scientist.

The next day, talking informally to a small group, he pulled out of his wallet a much-loved photo of his thirteen-year-old son. He spoke as carefully as he had before, but this time his voice was sad, worried, and fatherly. His son, he said, had become so frightened about climate change that he was debilitated, depressed, and disturbed. Some might have suggested therapy, Prozac, or baseball for the child. But in this group one voice said gently, “What about the Transition Initiative?”

If the Transition Initiative were a person, you’d say he or she was charismatic, wise, practical, positive, resourceful, and very, very popular. Starting with the town of Totnes in Devon, England, in September 2006, the movement has spread like wildfire across the U.K. (delightfully wriggling its way into The Archers, Britain’s longest-running and most popular radio soap opera), and on to the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. The core purpose of the Transition Initiative is to address, at the community level, the twin issues of climate change and peak oil—the declining availability of “ancient sunlight,” as fossil fuels have been called. The initiative is set up to enable towns or neighborhoods to plan for, and move toward, a post-oil and low-carbon future: what Rob Hopkins, founder of the Transition Initiative, has termed “the great transition of our time, away from fossil fuels.”

Part of the genius of the movement rests in its acute and kind psychology. It acknowledges the emotional effect of these issues, from that thirteen-year-old’s sense of fear and despair, to common feelings of anger, impotence, and denial, and it uses insights from the psychology of addiction to address some reasons why it is hard for people to detoxify themselves from an addiction to (or dependence on) oil. It acknowledges that healthy psychological functioning depends on a belief that one’s needs will be met in the future; for an entire generation, that belief is now corroded by anxiety over climate change.

Many people feel that individual action on climate change is too trivial to be effective but that they are unable to influence anything at a national, governmental level. They find themselves paralyzed between the apparent futility of the small-scale and impotence in the large-scale. The Transition Initiative works right in the middle, at the scale of the community, where actions are significant, visible, and effective. “What it takes is a scale at which one can feel a degree of control over the processes of life, at which individuals become neighbors and lovers instead of just acquaintances and ciphers. . . participants and protagonists instead of just voters and taxpayers. That scale is the human scale,” wrote author and secessionist Kirkpatrick Sale in his 1980 book, Human Scale.

How big am I? As an individual, five foot two and whistling. At a government level, I find I’ve shrunk, smaller than the X on my ballot paper. But at a community level, I can breathe in five river-sources and breathe out three miles of green valleys.

Scale matters.

We speak of economies of scale, and I would suggest that there are also moralities of scale. At the individual scale, morality is capricious: people can be heroes or mass murderers, but the individual is usually constrained by inner conscience and always constrained by size. While a nation-state can at best offer a meager welfare system, at worst—as the history of nations in the twentieth century showed so brutally—morality need not be constrained by any conscience, and through its enormity a state can engineer a genocide. At the community level, though, morality is complex: certainly communities can be jealous and spiteful and less given to heroism than an individual, yet a community’s power to harm is far less than that of a state, simply because of its size. Further, because there are more niche reasons for people to identify with their community, and simply because there is a greater per-capita responsibility, a community is more susceptible to a sense of shame. Community morality involves a sense of fellow-feeling, is attuned to the common good, far steadier than individual morality, far kinder than the State: its moral range reaches neither heaven nor hell but is grounded, well-rooted in the level of Earth.

STARTING WITH a steering group of just a handful of people in one locality, the motivation to become a Transition community spreads, often through many months of preparation, information-giving, and awareness-raising of the issues of climate change and peak oil. In those months, there are talks and film screenings, and a deliberate attempt to encourage a sense of a community’s resilience in the face of stresses. When members of the steering group judge that there is enough support and momentum for the project, it is launched, or “unleashed.”

Keeping an eye on the prize (reducing carbon emissions and oil dependence), Transition communities have then looked at their own situation in various practical frames—for example, food production, energy use, building, waste, and transport—seeking to move toward a situation where a community could be self-reliant. At this stage, the steering group steps back, and various subgroups can form around specific aspects of transitioning. Strategies have included the promotion of local food production, planting fruit trees in public spaces, community gardening, and community composting. In terms of energy use, some communities have begun “oil vulnerability auditing” for local businesses, and some have sought to re-plan local transport for “life beyond the car.” In one Transition Town there are plans to make local, renewable energy a resource owned by the community, in another there are plans to bulk-buy solar panels as a cooperative and sell them locally without profit. There are projects of seed saving, seed swapping, and creating allotments—small parcels of land on which individuals can grow fruit and vegetables.

“The people who see the value of changing the system are ordinary people, doing it for their children,” says Naresh Giangrande, who was involved in setting up the first Transition Town. “The political process is corrupted by money, power, and vested interests. I’m not writing off large corporations and government, but because they have such an investment in this system, they haven’t got an incentive to change. I can only see us getting sustainable societies from the grassroots, bottom-up, and only that way can we get governments to change.” In the States, the “350” project (the international effort to underscore the need to decrease atmospheric carbon dioxide to 350 parts per million) is similarly asking ordinary people to signal to those in power. If change doesn’t come from above, it must come from below, and politicians would be unwise to ignore the concern about peak oil and climate change coming from the grassroots.

The grassroots. Both metaphorically and literally. Transition Initiative founder Rob Hopkins used to be a permaculture teacher, and permaculture’s influence is wide and deep. As permaculture works with, rather than against, nature, so the Transition Initiative works with, rather than against, human nature; it is as collaborative and cooperative in social tone as permaculture is in its attitude toward plants and, like permaculture, is prepared to observe and think, slowly.

One of the subgroups that Transition communities typically use is called “Heart and Soul,” which focuses on the psychological and emotional aspects of climate crisis, of change, of community. Importantly, people are encouraged to be participants in the conversation, not just passive spectators: it is a nurturant process, involving anyone who wants to be a part. Good conversation involves quality listening, for an open-minded, attentive listener can elicit the best thoughts of a speaker. Giangrande says that the Transition Initiative—which has used keynote speakers—is also exploring the idea of keynote listeners as “a collaborative way of learning how to use knowledge.” When I asked exactly what that would involve, he couldn’t be specific, because it was still only an idea, which is revealing of the Transition process, very much a work-in-progress. The fact that they were trying out an idea without being able to predict the results has a vitality to it, an intellectually energetic quality, a profound liveliness.

The Transition Initiative describes itself as a catalyst, with no fixed answers, unlike traditional environmentalism, which is more prescriptive, advocating certain responses. Again unlike conventional environmentalism, it emphasizes the role of hope and proactiveness, rather than guilt and fear as motivators. Whether intentionally or not, environmentalism can seem exclusive, and the Transition Initiative is whole-heartedly inclusive.

While in many ways the Transition Initiative is new, it often finds its roots in the past, in a practical make-do-and-mend attitude. There is an interesting emphasis on “re-skilling” communities in traditional building and organic gardening, for example: crafts that were taken for granted two generations ago but are now often forgotten. Mandy Dean, who helped set up a Transition Initiative in her community in Wales, describes how her group bought root stocks of fruit trees and then organized grafting workshops; it was practical, but also “it was about weaving some ideas back into culture.”

In the British context, the memory of World War II is crucial, for during the war people experienced long fuel shortages and needed to increase local food production—digging for victory. In both the U.K. and the U.S., the shadow of the Depression years now looms uncomfortably close, encouraging an attitude of mending rather than buying new; tending one’s own garden; restoring the old.

To mend, to tend, and to restore all expand beautifully from textiles, vegetables, and furniture into those most quiet of qualities; to restore is restorative, to tend involves tenderness, to mend hints at amends. There is restitution here of community itself.

FOR ALL OF HUMAN HISTORY, people have engaged with the world through some form of community, and this is part of our social evolution. Somewhere deep inside us all is an archived treasure, the knowledge of what it is to be part of a community via extended families, locality, village, a shared fidelity to common land, unions, faith communities, language communities, co-operatives, gay communities, even virtual communities, which, for all their unreality, still reflect a yearning for a wider home for the collective soul. The nineteenth-century artist William Morris spoke of the gentle social-ism that he called fellowship: “Fellowship is life, and lack of fellowship is death.”

People never need communities more than when there are threats to security, food, and lives. The Transition Initiative recognizes how much we need this scale now, because of peak oil and climate change. But beyond this concrete need, the lack of a sense of community has negative psychological impacts on individuals across the “developed” world, as people report persistent and widespread feelings of loneliness, isolation, dispossession, alienation, and depression. Beyond a certain threshold, increased income does not create increased happiness, and the false promise of consumerism (buy this: be happy) sets the individual on a quest for a constantly receding goal of their own private fulfillment, while sober evidence repeatedly suggests that happiness is more surely found in contributing toward a community endeavor. (The Buddha smiles a tired, patient smile: “I’ve been telling you that for years.”) Community endeavor increases “social capital,” that captivating idea expressing the value of local relationships, networks, help, and friendships. A rise in social capital could be the positive concomitant of a fall in financial capital that a low-carbon future may entail.

Many people today experience a strange hollow in the psyche, a hole the size of a village. Mandy Dean alludes to this when she explains why she was drawn to the Transition Initiative: “One of the awful things about modern culture is separation and isolation; we’ve broken down almost every social bond, so the one bond left is between parent and child. In this extreme isolation, we don’t interact except with the television and the computer. We’ve lost something, and we don’t know what it is, and we try to fill it with food and alcohol and shopping but it’s never filled—what we’ve lost is our connection to our community, our place, and nature. Stepping back away from that isolation is very healing for people; getting people into groups where they can do things together starts to reverse that isolation.”

FOR HUNDREDS OF YEARS, nation-states have attacked communities. Earliest and most emblematic were the enclosures: when governments passed laws to privatize common land, the spirit of collectivity was undermined as surely as the site of it. The vicious system of reservations for Native Americans robbed people of communities of land and stole from them the communal autonomy central to their cultural survival. Indigenous people all over the world have found their language communities assaulted, fracturing even their ability to speak.

From the monster-enclosures of colonialism to the subtle but strangulating enclosures of Time, through which people ceased to “own” their own time, instead being corralled into the factory-time of industrial capitalism, the idea and the actuality of community has been eroded in countless ways. “There is no such thing as society”—the most sociopathic lie ever uttered by a British prime minister—was Thatcher’s summing up as she and Reagan broke the unions, and for decades agribusiness has destroyed the lives and dignity of campesinos in South America, while neo-liberalism has wreaked havoc on communities across the world. And there are seemingly trivial examples that nonetheless are cumulatively important; in contemporary Britain the mass closures of pubs tear the fabric that knits communities together.

The colonial powers practiced the policy of “divide and rule,” usually dividing one community from another, but in contemporary society there is a more insidious policy of “atomize and rule.” The world of mass media fragments real societies into solitary individuals, passive recipients of information, consuming the faked-up society that television, in particular, provides, and one result of this is that the public, political injustices that communities have habitually analyzed and acted upon (food-poverty, housing-poverty, fuel-poverty, or time-poverty) have been rendered as merely an individual’s private problems.

It’s interesting (and not a little sad) that although the French Revolution announced that it stood for three things, only two of these (Liberty and Equality) have survived in political parlance while the third, Fraternity, has been made to sound both quaint and unnecessary. For decades, the voice of the State has declared that community solidarity is occasionally dangerous (unions are “too powerful and need to be destroyed”) or, like fraternity, rather parochial. What, though, could be more parochial than the voice of the mass media? Rejecting the rainbow of pluralism (the magnificent myriad Other upon Other upon Other, the Pan-Otherness by which all communities are Other to someone), the mass media broadcasts itself in mono. Narrow. Singular. Very, very parochial in its tight and exclusive remit.

In the long fetch of the wave, the Transition Initiative should be seen as a new formulation of a very old idea. We are ineluctably and gloriously social animals. We want fellowship. We flock, we gather, we chirp, we howl, we sing, we call, and we listen. If the Transition Initiative is empowering for communities, that is because there is an enormous latent energy there to be tapped, so that communities may be authors of their own story, hopeful, active, and belonging, rather than despairing, passive, and cynical.

Naresh Giangrande, in Totnes, tells me about a session they are designing on the theme of Belonging. Belonging, of course, is a lovely boomerang of an idea—where do you belong? Can that place belong to you? “Through the Transition Initiative,” says Giangrande, “we can talk about things in public which are normally only talked about privately. We all have a deep wound about belonging to the Earth.”

The Transition Initiative, says Giangrande, is “a movement that could be world-changing. And it is heartwarming to see how good-natured and good most people are—it revives my sense of community. It completely contradicts the image of human nature in the media, portraying it as greedy and selfish, competitive, nasty, and unsocial. That’s a self-reinforcing prophecy. We’re setting up the reverse. And we’re asking: will you join us?” People have flocked to do so. At the time of this writing, there are 146 Transition Initiatives, and by the time you read this there will be far more.

One of its techniques is in strengthening all that is associative, and attempting to democratize power, with a fine understanding of that particular social grace which seeks to create what Martin Buber called The Between.

What is it, The Between? Fertile, delicious, and powerful, it is the edge of meeting. The cocreated place of pure potential, a coevocation of possibility. The delicate point of meeting between you and him. Between them. Between us. What is the geometry of The Between? I could explain best if we went down to the pub, you and I (mine’s a glass of red wine, anything as long as it’s not Merlot, yeuch, that’s like drinking cold steel), and the geometry of The Between is as simple and direct as the line of our eyes across the table. It’s horizontal, equal, fraternal. We might have a chat with a couple of the old farmers, and my pal the vicar might be there with his guitar and best of all is when the harpist plays, which he does, very occasionally.

Warm with conviviality and wine, I might wander home and switch on the television (except for the fact that I gave it away some years ago), and Sky News would be showing me a parade of celebrities, each making me feel that little bit more insignificant. Celebrity culture is an opposite of community, informing us that these few nonsense-heads matter but that the rest of us do not. Insidiously, the television tells me I am no one.

If I was Someone, I’d be on telly. In this way, television dis-esteems its viewers, and celebrity culture is both a cause and a consequence of the low self-esteem that mars so many people’s lives. So, the unacknowledged individual is manipulated into a jealousy of acknowledgment, which is why it is so telling that huge numbers of young people insist that when they grow up they want to be a celebrity. They are quite right. (Almost.)

That is nothing less than they deserve, for we all need acknowledgment (but not fame). We all need recognition (but not to be “spotted” out shopping). We all need to be known, we need our selves confirmed by others, fluidly, naturally. A sense of community has always provided these familiar, unshowy acts of ordinary recognition, and the Transition Initiative, like any wise community, offers simple acknowledgment, telling us we are all players.

“Mistaken, appalling and dangerous” is how the Transition Initiative has been described, which is the kind of criticism you covet, knowing that the speaker is an oil industry professional and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis. Others have criticized it for being insufficiently confrontational. There are also criticisms from within: a tension between those who prefer fast action and those who prefer slow consideration, for the movement is both urgent and slow. It is transformatively sudden, and yet uses the subtle, tentative questioning of long dialogues within communities, a very slow process of building a network of relationships within the whole community.

In the language of climate change science, there are many tipping points, where slow causations are suddenly expressed in dramatic, negative consequences. The conference I attended when I met the scientist speaking of his unhappy son was called Tipping Point, and in a sense the Transition Initiative places itself as a social tipping point, with dramatic and positive consequences where the sudden wisdom of communities breaks through the stolid unwisdom of national government.

“We’re doing work for generations to come,” says Giangrande. You can’t change a place overnight, he says, but you have to begin now in the necessary urgency of our time. “We’re facing a historical moment of choice—our actions now [are] affecting the future. Now’s the time. The system we know is breaking down. Yet out of this breakdown, there are always new possibilities.” It’s catagenesis, the birth of the new from the death of the old. The process is “so creative and so chaotic,” says Giangrande. “Let it unfold—allow it—the key is not to direct it but to encourage it. We’ve developed the A to C of transition. The D to Z is still to come.” Brave, this, and very attractive. It is catalytic, emergent, and dynamic, facing forward with a vivid vitality but backlit with another kind of ancient sunlight: human, social energy.

No comments :

Post a Comment