SUBHEAD: The ‘fast food culture’ of modern society has distanced most of us from a richness of experience.

By Matty Lynch on 1 February 2011 in Permaculture Media -

(http://permaculture-media-download.blogspot.com/2011/02/food-security-and-food-culture-by-matty.html)

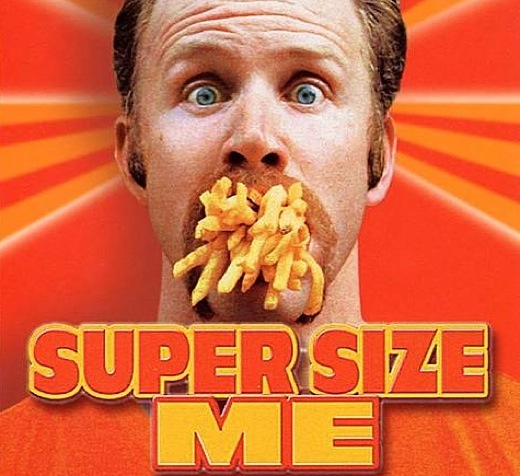

Image above: Detail of promotional poster for Morgan Spurlock's movie "Supersize Me". From (http://www.legendarystrength.com/remember-super-size-me).

Indeed, most of our major holidays and celebrations are centered around the experience of sharing a meal. Food culture and food security are closely linked: threats to one affect, and are affected by the other. A society which marginalizes the importance of celebrating and enjoying its food, also marginalizes the importance and richness of the living systems which support and create food.

The ‘fast food culture’ of modern society has distanced most of us from this richness of experience, with sobering results.

The Slow Food movement was spawned out of a response to the globalization of food production, and promotes sustainable food production by small local businesses to preserve and celebrate local and traditional food cultures. A society which celebrates the importance and richness of its food culture, creates resilient, happy communities: certain data* seems to indicate that average reported happiness is consistently lower in countries with a pervasive fast food culture [such as the USA] than in countries such as Cuba, which embrace and celebrate a locally produced, organic food system.

When a community is unable to provide for its own food needs, individuals are disempowered, despair sets in, and food aid must be imported. The community must be rebuilt with the knowledge and practical skills to produce enough of their own food to meet their needs, or a cycle of dependence can develop.

Agricultural yields are arguably at higher levels than ever in recorded history, yet in our world today, 1 out of 7 people will fall sleep tonight without access to enough food to lead an active and healthy life. A solid understanding of food culture and food security issues are important to a wellness practitioner because it will equip you with a foundation to act on a local scale, and know that you are improving the wellness of humanity on a global scale with your contribution. The long-term impacts of the modern conventional food system, which has only been in existence for the last 40 years or so, are only now starting to become more apparent.

Obesity levels and diet-related disease are at epidemic levels in the developed world, regional economies are being drained of their livelihoods by big agribusiness, while social and environmental impacts are being reported on by filmmakers, journalists, bloggers and other activists all over the world.

Once we understand the limitations and challenges created by the conventional food system, we can begin to identify opportunities to flourish within, while operating from outside the system: first, by producing enough of our own food to meet our survival needs, then to generate sufficient surplus to share in our local communities. It is here than we can access markets most efficiently, here that we can develop our most loyal customers, and it is here that the economic activities of our enterprise will make the most difference, because money will be cycled around local suppliers, distributors, and sellers to ehance and strengthen our community. ‘Market’ does not mean ‘places where we can sell crap’ to a permaculturist.

Instead, we view ‘markets’ as a vibrant community of people [think of your local farmer’s market], who share common needs that we can help to meet. When we can identify and meet these needs responsibly, ethically, and sustainably then we are rewarded with surplus cashflows to reinvest into our people, our enterprises, and our community.

For example, we can look for local heritage varieties of crops that have adapted to growing conditions in the area, and develop a niche demand for varieties that are unavailable on supermarket shelves because they may not be suitable for long-term transportation or storage. Or, we can look for high-value crops that can be integrated into our polycultures, increasing the biodiversity and resilience of our system, while increasing the diversity and resilience of our economic yield. Only when when our enterprise is able to competently serve the needs of our local community, should we look to developing our system to generate further surplus.

We expand our operations and systems organically, by careful observation, continuous improvement, and constant adaptation to changing long-term trends; and always, always conduct ourselves with respect to the ethics of permaculture, which underpin all of our work. It is vitally important that we look at what our land offers us, rather than impose our will upon the land.

For example, deciding arbitrarily that ‘I want to grow chamomile’ because there may be a market for it would not be in alignment with the permaculture ethic of Earth Care, while paying our employees less than a living wage would violate our ethical principle of People Care. Finally, hoarding all of our profits and not re-investing surplus back into our local communities not only serves to isolate ourselves from our basic need to connect meaningfully with other human beings around us, it would not honor the third ethical principal of permaculture: Resource Share.

See also:

Ea O Ka Aina: Permaculture as a Venture 1/25/11 .

By Matty Lynch on 1 February 2011 in Permaculture Media -

(http://permaculture-media-download.blogspot.com/2011/02/food-security-and-food-culture-by-matty.html)

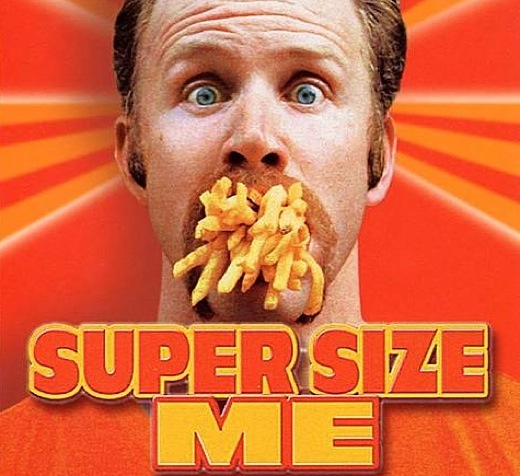

Image above: Detail of promotional poster for Morgan Spurlock's movie "Supersize Me". From (http://www.legendarystrength.com/remember-super-size-me).

“Food security has been defined as ...access by all people at all times to sufficient food for an active and healthy life. Food security includes at a minimum: the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and an assured ability to acquire food in socially acceptable ways (without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing and other coping strategies for example).” [(Online), Dieticians Association of Australia, www.daa.asn.au (2006.)]Food Culture refers to how we experience our food – from field to plate – and how it impacts our health, happiness, and sense of community. Perhaps the best way to explain the impact of food culture upon our wellness is to think of the way you feel, hear, smell, taste, and see another culture when you experience it through their cooking. So much of our cultural values are expressed in the way we grow, prepare, and share food.

Indeed, most of our major holidays and celebrations are centered around the experience of sharing a meal. Food culture and food security are closely linked: threats to one affect, and are affected by the other. A society which marginalizes the importance of celebrating and enjoying its food, also marginalizes the importance and richness of the living systems which support and create food.

The ‘fast food culture’ of modern society has distanced most of us from this richness of experience, with sobering results.

The Slow Food movement was spawned out of a response to the globalization of food production, and promotes sustainable food production by small local businesses to preserve and celebrate local and traditional food cultures. A society which celebrates the importance and richness of its food culture, creates resilient, happy communities: certain data* seems to indicate that average reported happiness is consistently lower in countries with a pervasive fast food culture [such as the USA] than in countries such as Cuba, which embrace and celebrate a locally produced, organic food system.

When a community is unable to provide for its own food needs, individuals are disempowered, despair sets in, and food aid must be imported. The community must be rebuilt with the knowledge and practical skills to produce enough of their own food to meet their needs, or a cycle of dependence can develop.

Agricultural yields are arguably at higher levels than ever in recorded history, yet in our world today, 1 out of 7 people will fall sleep tonight without access to enough food to lead an active and healthy life. A solid understanding of food culture and food security issues are important to a wellness practitioner because it will equip you with a foundation to act on a local scale, and know that you are improving the wellness of humanity on a global scale with your contribution. The long-term impacts of the modern conventional food system, which has only been in existence for the last 40 years or so, are only now starting to become more apparent.

Obesity levels and diet-related disease are at epidemic levels in the developed world, regional economies are being drained of their livelihoods by big agribusiness, while social and environmental impacts are being reported on by filmmakers, journalists, bloggers and other activists all over the world.

Once we understand the limitations and challenges created by the conventional food system, we can begin to identify opportunities to flourish within, while operating from outside the system: first, by producing enough of our own food to meet our survival needs, then to generate sufficient surplus to share in our local communities. It is here than we can access markets most efficiently, here that we can develop our most loyal customers, and it is here that the economic activities of our enterprise will make the most difference, because money will be cycled around local suppliers, distributors, and sellers to ehance and strengthen our community. ‘Market’ does not mean ‘places where we can sell crap’ to a permaculturist.

Instead, we view ‘markets’ as a vibrant community of people [think of your local farmer’s market], who share common needs that we can help to meet. When we can identify and meet these needs responsibly, ethically, and sustainably then we are rewarded with surplus cashflows to reinvest into our people, our enterprises, and our community.

For example, we can look for local heritage varieties of crops that have adapted to growing conditions in the area, and develop a niche demand for varieties that are unavailable on supermarket shelves because they may not be suitable for long-term transportation or storage. Or, we can look for high-value crops that can be integrated into our polycultures, increasing the biodiversity and resilience of our system, while increasing the diversity and resilience of our economic yield. Only when when our enterprise is able to competently serve the needs of our local community, should we look to developing our system to generate further surplus.

We expand our operations and systems organically, by careful observation, continuous improvement, and constant adaptation to changing long-term trends; and always, always conduct ourselves with respect to the ethics of permaculture, which underpin all of our work. It is vitally important that we look at what our land offers us, rather than impose our will upon the land.

For example, deciding arbitrarily that ‘I want to grow chamomile’ because there may be a market for it would not be in alignment with the permaculture ethic of Earth Care, while paying our employees less than a living wage would violate our ethical principle of People Care. Finally, hoarding all of our profits and not re-investing surplus back into our local communities not only serves to isolate ourselves from our basic need to connect meaningfully with other human beings around us, it would not honor the third ethical principal of permaculture: Resource Share.

See also:

Ea O Ka Aina: Permaculture as a Venture 1/25/11 .

No comments :

Post a Comment